The

British Armoured Car Force of the

Royal Naval Air Service had seen quite

a lot of the world before they found

their way to Roumania. They had done

their bit in Belgium, they had

wandered thence to Russia, and they

had sampled the roads of Persia; in

fact, a kind of supernatural instinct

seems to have led them to all the best

places for a lively scrap, and, as

soon as the liveliness was at an end

in one quarter of the globe, they were

off to another.

In

the late autumn of 1916 they had

abandoned Persia, having come to the

conclusion that it was completely

played out as a theatre of war, and

they had assembled at Odessa,

wondering where they should go next.

They definitely belonged to the

Russian Army, and they made up their

minds that it was up to the Russian

Army to keep them supplied with jobs.

Roumania had just entered the lists,

and for a time things seemed to be

going well with her, until General

Mackensen began his great push in the

Dobrudsha, and then the British

armoured cars said to themselves,

“Here is a job for us,” So they

appealed to the powers that governed

the Russian Army at that time, and

obtained permission to transfer

themselves to Roumania, and there

attach themselves to the Russian

forces operating in that country.

Of

course they knew in their hearts that

an armoured car is not really the same

thing as a ship, but when the white

ensign is fluttering above it, they

think and talk of it as though it were

a ship. The man who said that R.N.A.S.

means Really Not A Sailor was no

psychologist, and failed altogether to

appreciate the psychological effect of

the white ensign. When an officer in

command of a car receives his

instructions, he calls them his

Sailing Orders, and sometimes the

officer who writes them out in his

best official language, heads them

with the words "Sailing Orders” in

black and white. But, on the whole,

they are very careful with their

official reports, and all such

expressions as “Put the helm hard over

to starboard,” or “Proceed full speed

astern,” have been translated into the

lingo of the motor garage.

Towards

the end of November 1910 they found

themselves at Hirsova on the Dobrudsha

side of the Danube, where General

Sirelius of the 4th Siberian Army

Corps told them that they were just in

time for a big battle, and that he

wanted them to take an important part

in it. Things had been going badly of

late, for General Mackensen had been

mopping up Roumanian divisions on a

wholesale scale, and walking through

the Dobrudsha as though it were the

Unter den Linden. But there was just a

possibility that the advance had been

too rapid, and that a counter-attack

might find the enemy unprepared, and

with his supply columns many miles to

the rear. A Russian force, sweeping

down between the Danube and the Black

Sea, might be able to cut off the

enemy's forces, which had crossed the

river and were operating against

Bucharest, and cheery optimists among

the Russians even contemplated the

recapture of Cernavoda bridge and of

the port of Constanza.

The

push was timed to start on 29th

November, and the force of armoured

cars was ordered to be in readiness to

lead the attack. But when the day

arrived all these orders were

cancelled unceremoniously, and the

cars were told to proceed across the

Danube to a destination near

Bucharest. The truth of the matter

was, that the Roumanian Army defending

Bucharest had failed to hold their

positions, and the capital was in

imminent danger. The general in

command of the Russian forces

co-operating with the Roumanians had

at once sent out an S.O.S. signal, of

which the effect was, “For Heaven's

sake send us the British armoured

cars.” Commander Gregory, in charge of

the force, at once sent scouts to

examine the state of the roads, for it

is one thing for a general at

Bucharest to say he wants armoured

cars, and another thing for the people

in the cars to get them to him. The

scouts all reported that the roads

leading to the pontoon bridge across

the Danube were too bad for any

parliamentary language, and quite

unfit for motor traffic. So Commander

Gregory went to the Chief of Staff of

the 4th Siberian Corps, and told him

that it was beyond human possibility

to comply with the latest order that

the force had received. Incidentally

he relieved his mind by pointing out

that he had been given nothing but

contradictory orders, one on top of

another, for the past six weeks.

Now,

when General Sirelius heard from his

Chief of Staff what Commander Gregory

had been saying, he smiled blandly,

for the truth of the matter was that

he did not want to part with the

British armoured cars. Already the

Bucharest army was taking from him all

the best of his reserve battalions,

which were to have enabled him to

carry out the great push through the

Dobrudsha, and was transferring them

across the Danube to the defence of

Bucharest. The result was that the

great push had to be postponed, and

the general intended to wait until

fresh reserves could be sent up to

him. But here again his intentions

were frustrated, for it was not many

hours before another S.O.S. signal

came from Bucharest. “For Heaven's

sake make your push, or do something

to cause a diversion.” This was rather

hard on the general, first to take

away his reserves, and then to tell

him to make his push; but such things

are liable to happen when things are

going badly, and he consoled himself

with the thought that, at all events,

they had not succeeded in robbing him

of the armoured cars. So he ordered

that the push should commence next day

- 30th November.

The

British armoured cars were divided

into three squadrons, two of them to

operate from the village of Topalul

towards Ballagestii and a third from

the village of Panteleimon towards

Saragea. The morning broke dull and

misty, and the artillery soon found

that they were quite unable to observe

the effect of their shells; but soon

after noon it cleared up, as

Lieutenant-Commander Belt, in command

of Number One Squadron, was ordered

into action along the road running

from Topalul to Ballagestii. He found

that the enemy was leaving nothing to

chance; first there was a forest of

barbed wire entanglements, then

another forest fifty yards behind the

first, then the first line trenches

fifty yards behind that, and then the

second line trenches fifty yards

behind the first line.

The

road along which the cars had to

advance to the attack was no road at

all, but just an unmetalled track

running through cultivated fields. The

ground on either side of the track was

soft and uneven, for, though it had

not received any recent ploughing, it

was equally unprepared as a terrain

for fighting cars. Two Russian cars of

powerful build, carrying two maxim

guns each, had joined the British

squadron, and when they were ordered

to attack the enemy's trenches, they

went full speed along the track right

up to the barbed wire. They then

conceived the idea of turning off the

track and running along the barbed

wire, so as to enfilade the trenches

all along the sector. It was a bold

scheme, but it failed to take into

account the factor of specific

gravity. An armoured car is no fairy

with light fantastic toes to trip

nimbly over arable land. They had no

sooner left the track than they found

themselves firmly embedded in the soft

ground, with their flanks almost

touching the barbed wire, and

infuriated Bulgarians expressing their

indignation by means of a hot

fusillade.

Then

came a telephone message from the

Russian observation post, ordering one

of our light “Lanchester“ cars to go

in to support the Russian cars, and

incidentally to assist the Russian

infantry in launching an attack.

Lieutenant-Commander Belt sent

Sub-Lieutenant Lefroy, accompanied as

usual by a motor cyclist, whose job it

was to watch the progress of events,

and bring back reports from time to

time. Now, the ordinary practice when

going into action is to turn the car

at a respectful distance from the

enemy's lines, reverse the engine, and

approach stern first towards the

enemy. This is a fairly simple

operation on a metalled road, but when

there is no road worthy of the name,

the whole science of fighting an

armoured car has to be reconsidered.

Unfortunately, there was no time to

work out the problem, for the Russian

infantry were waiting to advance, and

Lefroy's main purpose was to lead the

way for them. He proceeded up the

track to the enemy's first line, the

Russian infantry followed, and the

great push had begun.

When

he had approached within a few yards

of the barbed wire, he decided that it

was high time to carry out the

ordinary manoeuvre of reversing the

engine, and advancing stern first.

But, first of all, he had to turn the

car round. Turning a heavy car on a

narrow farm-track is no easy operation

under the best of circumstances, and

when rifles, machine guns, and

artillery are devoting the main share

of their attention to frustrating the

effort, it becomes a decidedly

ticklish job. He had put the lever

over to the lowest speed when, as ill

luck would have it, a shell exploded

underneath the car and jambed the

speed-gear, so that he was doomed to

stick to his lowest speed until he

could get back to the repair shop.

Meanwhile his wheels were steadily

subsiding into the soft earth, and the

enemy was making things so

uncomfortably warm for him that he had

no alternative but to try and get out

of his tight corner. Luckily, he

managed to extricate his wheels, but

he did not enjoy the journey home at

the speed of a perambulator pushed by

a superannuated nursemaid suffering

from rheumatism, and with high

explosive shells following him

steadily all the way.

Next,

Lieutenant Walford was sent into

action with another light

“Lanchester.” By this time the enemy

had made up their minds that they did

not like armoured cars, and had become

obsessed with the idea that if their

rifles and machine-guns could only

pour enough lead into the brutes, they

would become discouraged and retire

gracefully from the action. This

theory suited the Russian infantry

admirably, for it enabled them to

advance under far pleasanter

conditions than they had anticipated.

When Walford got within forty yards of

the stranded Russian cars, the patter

of the bullets on his armour plating

grew louder and louder; but an

armoured car does not worry much about

bullets, so long as they do not come

through the loopholes. The trouble was

that they split into fragments, and

the fragments caused a kind of mist,

so that the driver of the car could

not see the track in front of him. In

trying to turn he did just the same

thing as Lefroy had already done

before him - got his wheels stuck in

the soft earth at the side of the

track. He succeeded, however,

eventually in getting round, and then

the maxim in the car opened fire on

the enemy, doing considerable damage

at that close range, until a bullet

came through a loophole and punctured

the maxim's water-casing, which keeps

the gun cool. This effectually put the

gun out of action, and there was

nothing for it but to take the car

back to safety. It is regrettable to

have to record that the personal

beauty of Lieutenant Walford and of

the driver of his car were completely

spoiled for the time being by the

nickel splashes of the enemy's

bullets. These had found their way

into the car, and dug themselves into

the faces of its occupants, until they

looked like the masterpieces of a

post-impressionist artist.

Meanwhile

the two Russian cars were hopelessly

stuck, and were being subjected to a

terrible fire from rifles,

machine-guns, and artillery, so

Lieutenant Commander Belt himself went

to the rescue. He had exactly the same

experience as his predecessors when he

tried to turn his car, and for nearly

a quarter of an hour he remained with

the front wheels of his car deeply

embedded in the mud.

“If

I was to tighten up the gears a

bit,” suggested the driver, “I think

we might get her to move.”

So

he got to work with a screw-driver,

while the enemy got to work with

artillery, maxims, and rifles, and

concentrated everything they could

bring to bear on the car. At last,

with a series of protesting snorts and

vigorous jerks, she began to move. By

this time it was quite dark, and

moreover the road had become pitted

with shell-holes, so that the journey

home promised plenty of excitement.

But there were the two derelict

Russian cars lying a few yards away

shrouded in gloom, and the thought of

leaving them to their fate was not an

easy one. There are times when it

requires more courage to avoid a

danger than to run into one, and this

was just one of those occasions.

Lieutenant-Commander Belt knew that

the result of any further attempt to

rescue the Russian cars would be that

the enemy would be able to rejoice

over three derelicts instead of two,

so he braced himself up to the

decision that there was no alternative

but to cut the loss. On his way back

through the dark he met another

“Lanchester,” coming to the rescue,

but this too he ordered to return, for

he knew it could do no good. It

afterwards transpired that three of

the crew of the first Russian car were

killed by a shell, and that the

remainder were badly wounded, but

managed to escape in the dark, as also

did the crew of the second Russian

car. The two cars had to be destroyed

by the Russian artillery.

Such

is the record of the first day's

fighting, so far as the armoured cars

were concerned in it. It must be put

to their credit that, by causing the

enemy to concentrate his fire upon

them, they had enabled the Russian

infantry to capture a hill on the left

flank, and to get a footing on another

hill on the right flank near the

river. This was something to the good,

but it was already becoming painfully

obvious that the enemy were fully

prepared, and that ground could only

be gained from them by means of a

ding-dong struggle. All through the

night the Russian infantry pressed

forward the attack, but only at the

cost of heavy losses, which made

General Sirelius parody the great

Augustus, exclaiming, “Varus, Varus,

give me back my reserves.” The truth

of the matter was that the breakdown

of the Roumanian forces defending

Bucharest had placed the Russian army

in the Dobrudsha in a most unenviable

position, and had completely ruined

the chances of a successful

counter-attack against Mackensen.

All

next day (1st December) the fighting

continued, and again the armoured cars

did valuable work. No more Russian

cars were available, but the British

cars kept on running through heavy

fire right up to the enemy's trenches,

pouring a hot fusillade into them, and

running back again before the

artillery could get their range

correctly. For two solid miles each

way they had to run the gauntlet of

bullets and shells, and the enemy

never left them in any doubt as to the

opinions he entertained about them,

for he devoted all the best of his

energies in their direction. On one

occasion, when Lieutenant Crossing had

brought his car within 300 yards of

the enemy, he noticed that a Russian

shell had made a neat gap through the

parapet, exposing to view a large

number of fleeing Bulgarians. He

immediately switched his machine-gun

on to them, and got through two belts

of ammunition before the high

explosive shells began to fall

uncomfortably close to him.

So

far the attack had been pressed mainly

from Topalul in the direction of

Ballagestii, and, though the Russian

infantry had advanced without

hesitation, they had gained but little

ground, and that little had been very

expensive in casualties. In fact, what

reserves had been left to General

Sirelius were now all used up, and by

the end of the second day's fighting

the whole Corps was so thoroughly worn

out that there was a grave danger that

a counterattack on the part of the

enemy might prove too strong to be

resisted by tired and dispirited

troops. When day dawned on 2nd

December the situation had become

critical.

At

9 o'clock in the morning Commander

Gregory was requested by the Russian

Staff to send two ears into action,

and he promptly complied with the

request. But the cars went into action

alone, unsupported by the Russian

infantry, who made no attempt to

advance. The bitter truth was that

they were in no fit condition to

advance, and the sending of the cars

into action was merely a device to

deceive the enemy into thinking that

the push was still in progress. It was

a vital necessity to conceal the fact

that the Russian troops were so badly

in need of rest and recuperation that

a counter-attack on the enemy's part

would find them incapable of adequate

resistance. For nearly two hours the

cars of Lieutenant Walford and

Sub-Lieutenant Gawler carried on this

pseudo-attack against General

Mackensen's army, dodging up and down

the road to keep the hostile artillery

from finding the correct range, and

pouring many hundred rounds of

ammunition into the Bulgarian

trenches. The notion of two armoured

cars fighting an army has something of

the farcical about it, which must have

appealed strongly to the British sense

of humour. The strange part of it is

that the ruse succeeded, and on that

part of the line the enemy attempted

no counter-attack, but patiently

waited to see what was going to happen

next.

It

was in the direction of Panteleimon

that the counter-attack was made, and

there Lieutenant Commander Wells Hood

with his squadron had been standing by

for orders during the past two days.

On 2nd December the enemy commenced an

attack in strong force, and

immediately the cars were ordered to

proceed along the road between

Panteleimon and Saragea to meet the

attack. There were three of them, and

they went into action at intervals of

150 yards along the road,

Lieutenant-Commander Wells Hood

leading. They soon came under heavy

shellfire, and when they were about

half-way to Saragea the rifles and

machine-guns opened fire on them. The

leading car was only 60 yards from the

Bulgarian trenches when the enemy were

seen to be advancing in open formation

- a long line of Bulgarian infantry

coming forward at the double. The

range was 400 yards, and the maxim in

the car soon began to make appreciable

gaps in the line. But the moral effect

of an armoured car is even greater

than the material damage it can

inflict; it is always a nasty job to

attack an object which is impervious

to rifle-fire, while it is pumping out

hot lead faster than a street-corner

orator can pump out hot air. The

Bulgarian infantry dropped back into

their trenches, and the maxim pumped

another 500 rounds into them there,

just to show them that there was no

scarcity of ammunition, in case they

should care to make another effort.

The

next manoeuvre was to turn the car

round, and to reverse towards the

enemy, so as to get near enough to

enfilade the trenches. There was an

ulterior object in this manoeuvre, for

the hostile artillery had found the

range of the ear, and shells were

falling too close to be pleasant. If

the car could only get close enough to

the Bulgarian trenches, the artillery

would be forced to discontinue their

attack, for fear of hitting their own

men. Such at least was the theory, but

in practice it did not prove

successful. The artillery shortened

their range, pursuing the car

relentlessly, until it became obvious

that the new position was untenable.

When the car started forward again the

engine suddenly stopped, and it was

discovered that the pressure petrol

tank had been pierced in two places by

bullets. This was an awkward

predicament at such a juncture, when

the car was within a few yards of the

enemy's trenches. But the driver

treated it as though it was all in the

day's work, and promptly switched on

to his gravity spare tank. The next

problem was how to start her up again,

and this was solved by the gunner.

Chief Petty Officer Vaughan, who,

without a moment's hesitation, jumped

out of the car, started her up, and

jumped in again, before any Bulgarian

sniper had time to realise his chance.

So they successfully got back to

Panteleimon, where they filled up with

water, repaired the petrol tank, and

took a fresh supply of ammunition

aboard.

Meanwhile

the two other cars were not enjoying

life quite so whole-heartedly.

Lieutenant Mitchell's car was about 40

yards from the road on the left-hand

side, and there it seemed to be stuck.

It had been noticed that the gun was

at its extreme elevation, and that

three of the crew were outside the

car, but what they were doing, or

trying to do, was not clear. The third

car, commanded by Lieutenant Ingle,

was also on the left hand side of the

road, about 400 yards from it, and

only a few yards from the Bulgarian

trenches. This car also seemed to be

stuck. The history of its exploits was

not known until the next day, but it

will be convenient to relate them

here.

The

car had run very nicely until it was

traversing No Man's Land, when the

soft wet earth clogged the wheels

badly, with the result that the engine

stopped at a spot uncomfortably close

to the enemy. Lieutenant Ingle jumped

out, and started her up, but after a

few yards she stopped again. Again

Lieutenant Ingle risked the chance of

stopping a bullet, and started her up

once more, but the result was just the

same; she stopped after a few spasms.

Lieutenant Ingle was indefatigable;

for the third time he tried to start

her up, and, in doing so, became a

handy target for some Bulgarian

sniper. A bullet struck him just above

the knee, breaking his leg, and at the

same moment the enemy's artillery

began to drop shells in the vicinity.

He rolled into a trench close to the

car, and ordered his men to do the

same. It was a lucky chance that he

did so, for immediately afterwards a

shell hit the car, twisting the turret

beyond recognition, and carrying away

the waterjacket of the maxim.

Strangely enough, however, it did very

little damage to the engine.

So

there were the whole of the crew

hiding in a trench on the wrong side

of No Man's Land, and the next thing

to happen was a Bulgarian advance

which swept right over them, Some

Bulgarian soldiers presently came up

to them, and intimated that they were

prisoners, and must march to the rear

of the Bulgarian lines. Then they

grasped the fact that Lieutenant Ingle

was wounded, and could not march, so

they solemnly went through the motions

of carrying a man on a stretcher, to

indicate that they were going back to

fetch one. By this time it was quite

dark, and when Lieutenant Ingle was

left alone to think things out, he

came to the conclusion that he did not

want to become a prisoner of war.

Slowly and painfully he started to

crawl out of the trench towards the

Russian lines. He knew that many hours

of darkness lay before him, and that

if he could only traverse the distance

before his strength failed, he ran a

very good chance of getting through

without being detected. That crawl

lasted exactly twelve hours - twelve

weary hours on all fours with one of

them broken. At daybreak some Russian

soldiers in their trenches saw a

British naval officer lying on the

other side of the parapet, and dragged

him into safety. Then they got a

stretcher and took him to the hospital

at Panteleimon.

In

the meantime things had been happening

all round Lieutenant Ingle, in which

he would have been keenly interested

under happier circumstances. As soon

as night had fallen the Russians had

counterattacked, and had succeeded in

driving back the Bulgarians for 300

yards. This again brought our cars

within the Russian lines, and it only

remained to send a party of men and

horses to tow them out of the mud. It

was not an easy operation in the dark,

especially when Bulgarian snipers

discovered what was happening; but

both cars were successfully recovered,

and those who worked hard and risked

much to recover them had their reward,

when they saw an enemy communiqué

reporting the capture of two British

armoured cars. It was the main feature

in the communiqué, for both

Germans and Bulgarians had an

unreasoning prejudice against the

cars, and hailed their capture in

grandiloquent phrases; nor did they

take the trouble to issue an amended

statement, when they found that they

had been counting unhatched chickens.

Of

the crews of these two cars it is

regrettable that all except Lieutenant

Ingle were taken prisoners, but it is

some consolation to know that the work

of the three cars between Panteleimon

and Saragea had most important

results, and that official information

was forwarded to the commanding

officer of the Armoured Car Force to

the effect that, had it not been for

the three cars operating at this

point, the Russian trenches would have

been captured, and the line broken.

General Sirelius took the trouble to

write an autograph letter of thanks to

the officers and men of the force, in

which he referred to their “brave and

unselfish work during the battle,” and

regretted that it had entailed such

heavy losses upon them.

The

battle was over, and the result was

profoundly unsatisfactory. It may have

produced a diversion, which for the

moment relieved the pressure on

Bucharest, but the original objective

of a sweep through the Dobrudsha

between the Danube and the Black Sea

down to Cernavoda had faded away like

a dream, leaving only the

consciousness of a heavy casualty

list, and a general feeling of

depression. The cars returned to

Hirsova, where the repair staff got to

work on them at once, anticipating

that it would not be long before they

were wanted again. In fact, the

general had applied for permission to

retain them with his division, and had

intimated that he hoped shortly to

renew the operations.

No

account of the battle of Topalul would

be complete without mentioning the

work of the medical staff attached to

the British armoured cars.

Staff-Surgeon G. B. Scott was in

command of them, and at once placed

all his resources at the disposal of

the Russian Senior Medical Officer. He

sent Surgeon Glegg with two sick berth

ratings and an ambulance to

Panteleimon, while he and Surgeon

Maitland Scott, with the rest of the

staff, attached themselves to the

hospital at Topalul. At six o'clock in

the evening of 30th November the

Russian wounded began to arrive, and

continued in a steady stream until

three o'clock the next morning. There

was only one Russian officer capable

of performing operations, and before

many hours he was completely worn out.

He appealed to the two British doctors

to take over all the operating work,

and this they did cheerfully, carrying

on until 4 a.m., when they finished

for the night and turned in.

On

1st December Staff-Surgeon Scott was

aroused early in the morning by the

Russian S.M.O., who had a new problem

to present. One day's fighting had

filled the hospital, and the battle

was to continue. The question was, how

to get the cases removed to a place of

safety. The only medical transport the

Russians possessed was a lot of

horse-drawn carts, which were very

slow and of small capacity. The only

possible solution of the problem was

to borrow some of the transport

lorries of the Armoured Car Force, and

convert them into ambulances.

Commander Gregory agreed to lend the

lorries for this purpose, and in a

very short time some of the ratings

belonging to the force were busy

fitting them up with naval cots and

spare stretchers, and covering the

floor with loose straw. By eight

o'clock in the morning the fleet of

improvised ambulances was not only

ready for service but was loaded up

with 116 wounded men, and off they

went on the road to Chisdarestii,

where the cases were to be placed on

barges and taken down the river to the

base.

It

is astonishing to find how little

sleep a man requires when necessity

compels him to keep awake. The two

naval doctors had been busy with

operations until 4 a.m., but at 8 a.m.

they were on their way to Chisdarestii

with the new British medical transport

section that had been improvised

within the last hour. It is equally

astonishing to find what versatility

there is in the average man, when

occasion calls for it. Before long

Staff-Surgeon Scott and his staff

found themselves playing the role of

road-makers, for there was one spot

between Topalul and Chisdarestii where

the road was quite impassable by motor

traffic. Fortunately Staff-Surgeon

Scott had anticipated this, and had

armed all the drivers and spare

drivers with picks and spades. By

picking away the road in places where

there was more than enough of it, and

transferring it to places where there

was a great deal too little, they made

quite a decent road, and all in the

space of half an hour. At Chisdarestii

they put all the wounded men safely on

board the barges, and then went back

for another load. The second trip

removed 84 men to safety, making a

total of 200 for the morning's work.

And then the two doctors went back to

the hospital, starting in again at 10

a.m. with the routine work.

On

this day (1st December) they were able

to get to bed at midnight, and it

requires no great effort to believe

that they slept soundly. But they were

up again early next morning for more

transport work, and they took another

300 cases to Chisdarestii before they

resumed the professional work at the

hospital - again at 10 a.m.

Three o'clock had struck on the

morning of 3rd December before they

were able to turn in, but they did so

with thankfullness in their hearts,

for they knew that the fighting was

over for the time being, and they had

been able to get through three days of

stress without any breakdown or

serious hitch in the medical

organisation. On turning out they

performed an abdominal operation on a

case, who had been brought in during

the small hours, and then accompanied

the heavy lorries with another batch

of cases to Chisdarestii, taking fifty

of them all the way to Hirsova to

relieve the pressure on the barges.

The lighter lorries could no longer be

used because the road had become too

bad. At Hirsova they found Lieutenant

Ingle, sent there from Panteleimon,

and they set his broken leg. In spite

of the assistance rendered by the

British motor-lorries, it was found

impossible to provide all the wounded

Russians with transport, and large

numbers of lightly wounded men had to

tramp the ten miles to Chisdarestii.

Staff-Surgeon

Scott mentions that at Topalul he and

his stall were treated with the utmost

kindness by the Russian Senior Medical

Officers and staff. The modesty of

this statement is admirable, but one

is left wondering where the Russian

medical arrangements would have been

without the fortuitous assistance of

the medical unit provided by the

British Navy. During the whole period

of the battle the two doctors and

their staff of sick berth ratings had

worked almost day and night, and by

their energy and resource in making

use of the transport lorries they had

averted the catastrophe of a hopeless

congestion at the field hospital. It

had been a period of gloom and

depression for the allied forces, but

the devotion to duty of these officers

and men, and the unflinching courage

of the combatants, both Russian and

English, endow the battle of Topalul

with a shining ray of light. It is the

courage which "mounteth with

occasion", that is the best brand of

all.

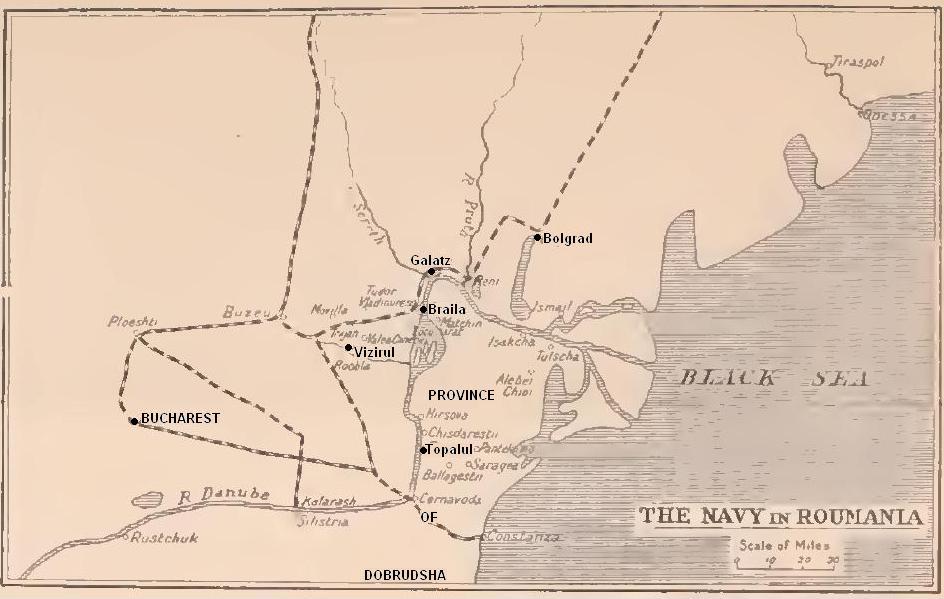

CHAPTER

XV

THE

RETREAT FROM THE DOBRUDSHA

(click

map to enlarge)

Those

were dark days for Roumania in

December 1916, when Mackensen's giant

strides had rushed an army through the

Dobrudsha, while on the other side of

the Danube the Austro-German forces

were steadily closing on Bucharest. It

is not for me to try and fix the

responsibility for her misfortunes,

even if it were possible to do so from

the mass of conflicting accounts which

have emanated from various

eye-witnesses; but a warning may not

be amiss that all such accounts must

be received with caution. When things

are going wrong, everybody blames

everybody else; such is human nature.

A distraught staff officer eases his

mind with a few forcible expressions

about the regimental officers, while

the regimental officers are equally

eloquent about the staff officers; and

the General sends for his Chief of

Staff in order to blow off steam about

the War Office and the Government -

all in the strictest confidence. When

two nations, very wide apart in race

and national characteristics, join

hands for the purpose of waging war,

and when, moreover, the alliance is

based, not upon an old-established

friendship, but upon political

expediency, it would be strange if, in

the hour of disaster, each did not

ascribe the chief share of the blame

to the other.

In

the Dobrudsha a Russian army had been

striving to stem the tide of

Mackensen's onslaught, and had even

attempted a counter-attack to push him

back beyond the Cernavoda Bridge. But

on the eve of that counter-attack all

the reserves had been hastily snatched

away from General Sirelius, and thrust

across the Danube in a desperate

effort to save the Roumanian army

which was defending Bucharest. The

counter-attack was a failure in all

except the spirit shown by the Russian

troops, who throughout the battle of

Topalul were faced by greatly superior

artillery, and except the courageous

efforts made by the British armoured

cars. If bravery alone could win

battles, Mackensen's army would have

suffered a heavy defeat that day, but

unfortunately in modern warfare a

great deal more than the soldiers'

heroism is required to gain success.

The fighting quality of every

individual man may count in the long

run, but, however brilliant it may be,

it is of no avail if the great machine

behind it is faulty.

So

the Russian army in the Dobrudsha,

denuded of its reserves, failed to

drive back the enemy, and was on the

point of sitting down to recover its

breath, when the news came through

that Bucharest had fallen. It was a

staggering blow, not only on account

of its political aspect, but also

because it exposed the flank of the

Dobrudsha army. It must be remembered

that General Sirehus had been asked to

make his great effort at Topalul

before fresh reserves had had time to

reach him, in order to cause a

diversion, and so relieve the pressure

on the Roumanian army before

Bucharest. The fall of the capital,

therefore, added another failure to

the list of those objectives which he

had attempted to secure. Moreover, it

placed his army in serious jeopardy.

The general, however, had no such word

as "panic“ in his vocabulary; he

immediately sought some means of

putting heart into his dispirited

troops, and his mind, surveying the

events of the past few days, lingered

over the work of the British armoured

cars.

“Give

me the list of those Englishmen in

the cars who have been recommended

for decorations,” he said to his

aide-de-camp. The list was handed to

him, and he ran his eye down the

sheet. “Tell the Chief of Staff that

I want a full parade of the division

to-morrow morning,” he said, “and

send a note to Commander Gregory to

tell him that I want to see these

men there.”

On

7th December 1916 the general

presented the crosses and medals of

St. George to the men of the British

armoured cars before a full muster of

his troops, and when the presentation

was over he made a little speech to

thank them for what they had done.

Then he turned to his troops and told

them about the work of the armoured

cars.

“On

2nd December,” he said, “the enemy's

forces made a strong counter-attack

on our left flank at Panteleimon. It

was a critical moment, for I had no

reserves available, and if the enemy

had broken through our line, it is

impossible to say what might not

have happened. It was then that the

squadron of British armoured cars,

under Lieutenant-Commander Wells

Hood, went right beyond our first

line and poured into the advancing

infantry of the Bulgarians such a

heavy fire that they were obliged to

get back into their trenches. Their

counter-attack was broken up, and

our lines were saved. That was at

Panteleimon. At Topalul our English

comrades were performing similar

feats. Bulgarian prisoners who have

been brought in declare that no less

than half their casualties have been

due to the fire of the armoured

cars.”

This

parade was held near Braila, on the

left bank of the Danube, where the

railway from Bucharest into Southern

Russia begins to skirt the river. The

place was in a state of hopeless

confusion, for Roumanian fugitives,

both soldiers and civilians, were

streaming through it, so that the

railway and the roads were blocked by

them, and only the river was left to

the Russians as a line of

communication. Here Commander Gregory

received orders from the staff that

the armoured cars were to cover the

right flank of the army during its

retreat from the Dobrudsha, and with

these orders he hastened back to

Hirsova, where his force was carrying

out a hurried refit.

During

his absence at Braila he had left

Lieutenant Commander Belt in charge,

and this officer had been informed by

General Sirelius that Hirsova was

liable to be attacked by the enemy at

any moment, and that he had better

make all preparations for removing the

cars and their gear down the river.

The advice was doubtless excellent,

but how to act upon it was a problem.

The quay was in a state of

indescribable chaos; all the barges

alongside it were thronged with

soldiers and civilians, every man of

them bent upon his own aims; the

soldiers were loading up military

stores, and the civilians were

struggling to evacuate as much as they

could of their household furniture and

stock-in-trade. There was no one in

authority to procure any semblance of

order, and consequently every one was

getting in every one else's way, so

that none were making much progress

with the work. Lieutenant-Commander

Belt saw at once that drastic measures

were necessary, if the property of the

Armoured Car Force was to be saved. He

obtained the necessary sanction to

commandeer a couple of barges, and,

accompanied by an armed guard, he went

down to the quay and commenced to load

up all the heavier cars, the damaged

cars, transport cars, spare stores and

ammunition, and finally the sick men

and those of the force who would not

immediately be required. This left a

squadron of light fighting cars, a few

transport ears for supply, and a

sufficient number of men for present

needs.

The

mobile force, which was thus reserved,

was intended for the defence of

Hirsova. There was some danger that

Austrian monitors might come down the

Danube and attack the town during the

evacuation, and in that case the

armoured cars would offer the best

form of rear-guard on account of their

mobility. As things turned out,

however, the monitors neglected their

opportunity, and, when all the

inhabitants and all the troops had

made good their retreat, the armoured

cars received orders that they could

leave the place to its fate.

Rain

had been falling steadily for several

days past, and consequently the roads

were in a more horrible condition than

usual. Commander Gregory had taken the

precaution of reconnoitring them, in

order to ascertain which of them

offered some possibility of escape,

and the result of the reconnaissance

was that they had all been placed upon

the black list with the exception of

the road running eastwards to Alebei

Chioi. Thither they started oil at

daybreak on 14th December, and a

tedious journey they found it. Every

now and then they came across a hole

in the road big enough to swallow a

pantechnicon, and covered over with an

unappetising mixture of mud and water

about as thick as pea soup. The forty

odd miles occupied the whole of the

day, and some strong language was

heard on the road from Hirsova to

Alebei Chioi. By the time they reached

their destination they all felt quite

ready for a nice hot supper followed

by bed; but when the sailor goes

a-soldiering he learns, among other

things, that nice hot suppers and beds

are not always to be picked up when

they are wanted. It is no longer a

case of going below to the mess deck

and sitting down at a nice clean

table, while the mess cook brings

something fragrant and steaming from

the galley; but he has to suffer an

introduction to the mysteries of the

commissariat and the field kitchen,

and the hunt for billets.

At

Alebei Chioi the village was under

Roumanian control, and, to make

matters worse, it was full of Austrian

prisoners. For some time the men of

the armoured cars could find no

accommodation at all, and when at last

they tumbled into some kind of a place

with a roof to it - well, it is best

not to go into details. Suffice it to

say. that previous occupants had

negligently left a few little things

behind them. Of course it was

inevitable that one of these desirable

residences should be christened the

Ritz, and another should become known

as the Carlton. That is where the

Britisher scores every time over the

Hun and most of the other tribes of

the earth - his sense of humour never

fails him. In such quarters they spent

the next two days, and then came an

order from General Sirelius that they

should proceed at once to Braila,

there to fill in an ugly gap in the

Russian lines, which was threatening

to grow wider at any moment. Just as

they were about to start in the early

morning, the clattering of a horse's

hoofs was heard coming up the road,

and a mounted orderly drew rein in

front of them. He had ridden in hot

haste with an urgent message from the

general: “The enemy has broken through

the lines in two places during the

night. Dobrudsha army in full retreat.

Cancel all previous orders, and

proceed without delay to Tulscha. Two

barges will be sent there to meet you,

and bring you up the river.”

So

the Dobrudsha was to be resigned to

the enemy, and the last flickering

hope that it might be held until

sufficient force could be collected to

drive Mackensen southward, had died

out. At Tulscha they found another

scene of wild confusion, consequent

upon an order to evacuate the place

within forty-eight hours. There were

no other means of retreat than by boat

or barge up the Danube, or by road to

Isakcha, where there was a pontoon

bridge across the river. Needless to

say, the more favoured of these two

routes was the river, and consequently

all floating craft was in great

demand. The two barges referred to in

the general's despatch were either

mythical, or had been commandeered

long ago by some distraught army

officer, who was not likely to have

made particular enquiries as to

whether they were intended for some

one else. After many hours, Commander

Gregory succeeded in securing the

whole of one barge to take the

armoured cars to Reni, and half of

another to take the lorries, stores,

ammunition, and provisions to Ismail.

He had just completed this

arrangement, when a new problem was

suddenly brought to his notice.

“How

about the nurses of the Scottish

Women's Hospital?“

This

hospital had sent a unit to accompany

a Serbian division fighting in

Roumania. The division had been badly

cut up, and very little was left of

it, but the ladies of the Scottish

Hospital had remained to carry on

their good work, and found more than

enough occupation in ministering to

the soldiers of the Russian Army. They

had recently been stationed at Braila,

where some 8,000 wounded soldiers had

been collected from the scenes of

fighting on the Bucharest side of the

Danube. And now they were lending

their aid to the Russian medical units

attached to the Dobrudsha army.

The

problem of their evacuation from

Tulscha was solved by invoking the aid

of Sub-Lieutenant Turner, who proudly

escorted his charge on board a barge,

and, having signed a receipt for them

and for the heavy transport lorries,

which were also placed under his

charge, he shoved off en route for

Ismail, whence they were to proceed to

Bolgrad. The light transport cars were

taken by Lieutenant-Commander Belt

along the road to Isakcha, and over

the pontoon bridge to Bolgrad. The

fighting cars went by barge with

Commander Gregory to Reni. Thus, by a

process of devolving his

responsibilities, the commanding

officer succeeded in shaking the

chaotic dust of Tulscha from his feet.

The

story of the fighting cars is the one

which most concerns us at the moment,

for the adventures of the transport

lorries and the nurses belong to other

realms than those of naval operations.

When the cars reached Reni, they were

so badly shaken by the rough roads

they had traversed in the Dobrudsha

that they had to be handed over to the

repair stall for a hurried refit. It

was fortunate that just at this time

some extra cars arrived by train from

Archangel, brand new from England. For

the 4th Siberian Corps at Braila were

sending S.O.S. signals, of which the

burden ran, “For Heaven's sake send us

some of the British armoured cars.”

Now there was a liaison officer

attached to the force, and there was

also at Reni an officer belonging to

the Russian armoured cars. With these

Commander Gregory consulted as to the

prospects of armoured car operations

in the vicinity of Braila. Their

advice was the same as that of Punch

to young persons about to get married

- Don't.”

“The

roads round Braila,” they said, “are

quite impossible for armoured cars.

If you send those nice new cars of

yours there you will lose them. The

best thing you can do is to take the

whole of your force to Odessa, and

there wait upon events. That is what

the Russian armoured cars are going

to do.”

But

Commander Gregory was as obdurate as

are most of the young people to whom

Punch offered his advice.

“You

see, it's this way,” he said. “We

were sent out here as a fighting

force, and the first duty of a

fighting force is to fight. I say

nothing against Odessa as a

delectable place for a rest cure,

but it is not the kind of place for

a fighting force, not at present.

And if all the Russian armoured cars

are going there, that seems to me an

excellent reason why the British

cars should stay within easy reach

of the firing-line.”

Of

course he put it more politely than

this, but he left no doubt as to the

state of his mind on the subject. So

the Russian cars went to Odessa, and

the British cars remained at Reni,

except a special flying squadron which

was sent under the command of

Lieutenant Smiles to Braila. The story

of the achievements of this squadron

is told in another chapter.

On

21st December the town of Tulscha fell

into the hands of the enemy, and from

that moment the Danube Army ceased to

exist. In its stead a new army was

formed under the title of the Sixth

Army, and to this the British armoured

cars were now attached. Commander

Gregory, after conferring with

Headquarters, decided to collect all

the remainder of his force at Galatz,

where they would be within call of the

Army based on Braila if any urgent

need for their assistance should

arise. In making this decision he knew

that he was incurring considerable

risk, for, in the event of a sudden

retreat, it was very doubtful whether

he would be able to extricate his

force. There were no adequate roads

behind Galatz leading to the rear; the

railway was blocked with Roumanian

refugees, while the stretch of river

between Galatz and Reni was likely to

be commanded before long by the

enemy's artillery. On the other hand,

there was the prestige of British arms

to be considered, and this

consideration was enough in itself to

determine him to remain near the

firing-line up to the last possible

moment.

The

repair staff, by working night and

day, had made every one of the

lighting cars fit for immediate

service, when they were placed on a

barge and taken up to Galatz. There

they were joined by the light

transport cars, brought from Bolgrad

by Lieutenant Commander Belt, after

some minor adventures with an Austrian

aeroplane near the demolished pontoon

bridge at Isakcha. The heavy transport

lorries also found their way to

Galatz, and so did the doctors and

nurses of the Scottish Women's

Hospital. In fact, none of the British

contingent found the charms of Odessa

powerful enough to entice them from

the vicinity of the firing-line.

Of

the formation of a second special

squadron under Lieutenant-Commander

Wells Hood, to operate in the

neighbourhood of Tudor Vladimireseu,

not much need be said, for the roads

there were found to be quite

impossible for armoured cars. The

squadron left Galatz in a blinding

blizzard, lost their way several

times, eventually arriving at Tudor,

where they reconnoitred the roads in

several directions, but were obliged

to condemn them all. They had

considerable difficulty in getting

back to Galatz again, for the main

road was being continually cut up by

heavy artillery retreating eastwards.

The

next event was the decision to

evacuate Braila, the base from which

Lieutenant Smiles's squadron was

operating, and Commander Gregory

therefore sent a telegram to recall

him. But late in the evening of New

Year's Day an urgent message came

through from General Sirelius, begging

that the squadron might remain with

him, and undertaking to place at their

disposal a special train to take them

from Braila to Galatz at the last

moment.

“The

cars,” he said, “have established

such an ascendency over the enemy

that he never attacks when they are

present, knowing that he is sure to

suffer heavy losses by doing so,

and, moreover, the cars produce a

great moral effect upon my own men,

which is invaluable to me at this

critical juncture.”

So

Commander Gregory cancelled the order

recalling Lieutenant Smiles, sent him

two new cars to take the place of two

which had been damaged in the

fighting, gave him a fresh supply of

ammunition, and wired to the general

that the squadron was to remain at his

service.

From

the quayside at Galatz they could see

a fierce battle raging in the

Dobrudsha - the last desperate effort

to contest Mackensen's advance. Far

and wide across the long stretch of

flat country great fountains of smoke

kept on shooting up into the sky, and

mingling with the river mists, while

the bursts of the shells gave a lurid

tinge of red to the overhanging pall.

As a spectacle it was magnificent, but

to the watchers at Galatz it was all

too evident that the Russian artillery

was no match for that of the enemy,

and that the Russian infantry was

everywhere being driven back by

superior numbers. In the evening of

2nd January Matchin - the last town in

the Dobrudsha - fell into the enemy's

hands, and nothing now remained but to

extricate the Russian troops by

withdrawing them across the river.

It

is a curious illustration of the

uncertainties of war that on that very

morning the General commanding in the

Dobrudsha had actually been

contemplating an offensive, and three

cars belonging to Lieutenant Smiles' s

squadron had been sent across the

Danube in the afternoon to assist the

attack. When they arrived, however,

the whole situation had changed; the

Russians had been shelled out of their

positions, and, instead of expecting

to advance, the general was now

wondering whether he could get his

forces out of the tight corner in

which they were placed. The three cars

proceeded to a position 400 yards in

advance of the Russian lines, and did

not drop back until the evening. One

car developed engine trouble, and had

to be towed home, while another was

ordered to return, as it was a heavy

car with a 3-poundcr gun, which could

not be used advantageously after dark.

This left Sub-Lieutenant Kidd in a

light Ford car abreast of the Russian

first-line trenches, where he remained

after the commanding officer of the

Cossacks had announced his intention

of retiring the whole force from the

trenches.

For

another quarter of an hour he kept up

an intermittent fire on the enemy,

while the Russian infantry made good

their retreat, and then he slowly

followed them - the sole barrier

between the Russian forces and

Mackenscn's advancing army. A small

body of cavalry were just ahead of

him, and he followed them slowly

towards the pontoon bridge, until he

came to the last line of Russian

trenches, where he found some infantry

in possession but on the point of

retiring. He had no definite orders,

but he considered that it was his job

to see the whole of the Russian army

off the premises and over the river

before he himself left the Dobrudsha.

So he waited for twenty minutes to let

the infantry get away, keeping his

machine-gun rattling away from time to

time at the unseen foe. It was very

dark and very foggy, and he could not

help speculating upon the chances of

running his car into a shell-hole, and

so losing it. At last he moved on

again, picking his way very cautiously

through a thick bank of fog. Presently

a voice hailed him through the

darkness. It was the Cossack

commander, who wanted to thank him for

what he had done.

“They're

all over the bridge,” he said,

“cavalry and all.”

“Where

is the bridge?“

“Here,

you've just come to it; and we must

hurry up and get across, for our

fellows are going to blow it up.”

So

Sub-Lieutenant Kidd splashed through

the mud on to the pontoon bridge - the

very last unit of the allied forces to

leave the Dobrudsha. Less than an hour

later the bridge was no more.

At

Galatz there was a scene of bustle and

activity, for it was obvious that in a

few hours the town would be subjected

to bombardment, and all the available

barges were being loaded up with

stores, ammunition, and everything not

immediately required by the defending

force. The army from the Dobrudsha had

brought with them a large number of

sick and wounded, and it was fortunate

for these men that the nurses of the

Scottish Women's Hospital were at

Galatz to receive them. There was also

a unit of the British Red Cross

Society under Dr. Clemow and Mr.

Berry. The former is an English doctor

who has spent many years of his life

at Constantinople, and whose intimate

knowledge of the Near East and its

inhabitants made him a very valuable

asset to the medical forces in

Roumania. All the nurses stoutly

refused to leave Galatz until the last

possible moment, and the Russian

staff, finding that neither argument

nor entreaty produced the least

impression, besought Commander Gregory

to intervene. He effected a compromise

by persuading them to transfer their

hospital to a big barge, where they

could carry on with their work, and

then shove off at once when the first

shells began to fall on the town.

Here

are a few extracts from letters

received from some of the nurses.

“Commander

Gregory of the British Armoured Car

Corps sent down a message to say

that in the last resort he would see

us out, so we were able to work with

quiet minds. We owe a great debt to

Mr. Scott, surgeon to the British

Armoured Car Corps, who asked us if

he could be of any use. I sent back

a message to say that we should be

most grateful, and he worked with us

without a break until we evacuated.

He has just pointed out to me that

we operated for thirty-six hours on

end the first day, with three hours

break in the early hours of the

morning, and, as we had been working

twenty-four hours before that -

admitting patients, bathing, and

dressing them - you can imagine what

a time we had. Dr. Corbett has also

been calculating, and she says we

worked sixty-five hours on end with

two breaks of three hours' sleep. We

came out of it very fit - thanks to

the kitchen.

“A

Roumanian officer talked to me about

Glasgow, where he had once been, and

had been 'invited out to dinner, so

he had seen the English custims.' It

was good to feel those 'English

custims' were still going quietly

on, whatever was happening here -

breakfasts coming regularly, and hot

water for baths, and everything as

it should be. It was probably

absurd, but it came like a great

wave of comfort to feel that England

was there - quiet, strong, and

invincible behind everything and

everybody.”

Yes,

England was there, to stand by

Roumania in her hour of trial, even as

she had stood by Serbia; even as she

had shared in the retreat from Mons,

and more recently in the retreat from

the Isonzo. Since the war began

England has always been there, in

every part of the world where fighting

was to be done - in the conquest of

the Cameroons, of East Africa, of

South-West Africa, in the advance

across the plains of Mesopotamia, and

over the hills of Palestine. Sometimes

alone and sometimes aided by her

Allies, wherever the guns have been

fired in anger, by sea or by land,

England has been there.

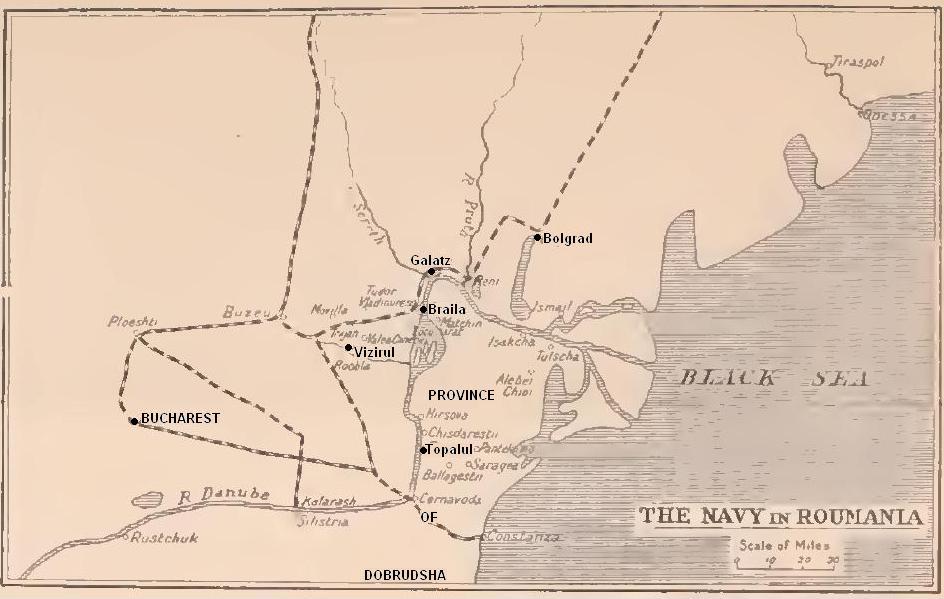

CHAPTER

XVI

THE

BATTLE OF VIZIRUL

(click

map to enlarge)

When

Lieutenant Smiles left Reni on 21st

December 1916, with a party of eight

officers, five chief petty officers,

and thirty-seven petty officers,

forming a special service squadron of

armoured cars to assist the 4th

Siberian Corps at Braila, the

situation had already become critical.

Bucharest had fallen, and the Russian

Army in the Dobrudsha was being

steadily driven back by superior

forces, while its right flank was all

the time exposed to attack from across

the Danube. In fact, it had alreadv

been decided that the Dobrudsha must

be evacuated, and the next problem was

how to extricate the Russian troops on

the other side of the river, and bring

them back to the line of the Sereth,

or any other line which it was

possible to hold. One of the virtues

of the armoured car is that it can be

as serviceable for a retreat as for an

attack, its mobility enabling it to

harass the advancing enemy up to the

last moment, and then make good its

escape.

Lieutenant

Smiles is an Irishman by birth, and

has the Irish gift of quick intuition,

which is invaluable to one whose

responsibilities continually call for

promptness of decision. He had served

with the armoured cars in France,

Belgium, and Persia, and had just

recovered from a wound received in the

Dobrudsha, but this did not deter him

from volunteering to lead the special

squadron, which was sent off in a

hurry to Braila upon receipt of a

message from General Sirelius

earnestly soliciting their assistance.

He took with him two heavy cars and

six light Ford cars, as well as

lorries for the transport of

ammunition and stores. These all

proceeded by barge to Braila, where

they were unloaded and prepared for

immediate action. The force was then

divided into two sections, one going

to Movila under the command of

Lieutenant Hunter and the other, under

Lieutenant Smiles, proceeding to Valea

Canepei. It was not long, however,

before the squadron was united again,

for the roads in the direction of

Movila were found to be unfit for

armoured cars, and Lieutenant Hunter

returned to Braila, proceeding thence

to Valea Canepei to rejoin the rest of

the squadron.

At

Valea Canepei General Sirelius greeted

the British officers by inviting them

all to lunch with him, for he had a

warm place in his heart for the

armoured cars. The next business was

the inspection of the front, which was

carried out the same afternoon by

Lieutenant Smiles, in company with

Lieutenant Edwards and Chief Petty

Officer MacFarlane. The Huns must have

scented trouble in store for them, for

they greeted the trio with an extra

dose of shells. Colonel Bolgramo, who

was in command of the brigade at that

point, conducted the party and showed

them all the beauties of the place,

including the village of Roobla in the

distance, where enemy troops were said

to be billeted in large numbers.

Lieutenant Smiles called to mind a

similar scene somewhere in France, and

remembered how the heavy cars there

used to wander up towards the enemy's

trenches, blaze away with 3-pounder

guns at certain objects behind their

lines, and then, when the Hun

artillery began to fmd the range of

them, used to dodge back to safety. He

saw a glowing prospect of playing the

same kind of game on the road to

Roobla.

Next

day at dawn, Lieutenant Lucas-Shadwell

went into action with the “Ulster”

heavy car, and started to demolish the

village of Roobla. On the east side of

the road the houses were stoutly

built, and it was said that the enemy

had a battery there hidden behind two

of the houses, Lucas-Shadwell found

the range at 1,200 yards, and blew

those two houses into little chunks.

Then he turned his attention to the

west side of the road, where the

houses were more flimsy, and where the

troops were supposed to be billeted,

and he felt his way systematically up

and down the village, firing

deliberately and taking careful

observation of the fall of the shells.

He spent just a quarter of an hour at

it, and then, according to orders,

brought his car out of action. It was

not until he was on his way back that

the Hun artillery woke up and started

to speed him on his journey. The

scouts at the advanced base reported

that he had done good execution.

Next

morning another heavy car, a

“Londonderry,” commanded by

Sub-Lieutenant Henderson, went into

action, while the "Ulster” was held in

reserve. The “Londonderry“ is a bit

top-heavy, and consequently difficult

to steer. Lieutenant Smiles

anticipating that there might be

trouble with it, came up behind on an

ordinary bicycle, which he had

borrowed from a Russian officer, and

ordered the “Pierce Arrow“ lorry to

stand by with a couple of tow-ropes in

case of accidents. His orders to

Henderson were to bombard Roobla and

the roads round about it, not to

remain in action more than fifteen

minutes, not to attempt to go beyond a

certain shell-crater in the road, and,

if he got stuck, to fire three

rifle-shots in quick succession. The

anticipation of trouble was an

intelligent one, for the “Londonderry”

had no sooner reached the Russian

advance post than it slid gracefully

into a ditch. Smiles at once cycled

back to Vizirul for the “Pierce Arrow“

lorry, at the same time ordering

Sub-Lieutenant MacDowall to take the

“Ulster” into action.

Then

came the job of pulling the

“Londonderry “out of the ditch. It was

rather a long job, and it was not

rendered any easier by the enemy's

artillery, which always showed a

marked partiality for a stationary

target in the shape of an armoured

car. It should, however, be observed

that the artillery was very inferior

to that brought against us in the

Dobrudsha. The truth of the matter was

that the enemy forces closing on

Bucharest had moved so rapidly that

their heavier pieces were still many

miles to the rear. The tow-ropes were

attached to the stranded

“Londonderry,” and the “Pierce Arrow“

began to haul, but at first no visible

impression was produced. Then various

devices were tried to ease the path of

the sunken wheels. The workers were so

much absorbed in their task that they

had no time to look round towards the

enemy's lines, and worked on in

blissful ignorance of the fact that

the Bulgarian troops had climbed over

their parapet and were advancing

steadily towards them. At last, with a

squelching sound, as the wheels were

drawn out of the mud, the

“Londonderry“ began to move, and in a

few minutes was on her way along the

road towards Vizirul. Less than half

an hour later the enemy were in

possession of the spot where she had

been lying.

The

“Ulster” returned about the same time,

and Lieutenant Smiles called at

Colonel Bolgramo's Headquarters for

further orders.

“Do

you see that long hne of infantry?“

said the colonel, waving his hand

towards the enemy. “They are

advancing on Vizirul, and, if they

take it, Heaven only knows how we

shall extricate ourselves. I want

you to go at once to the general,

and ask leave to send all your cars

up to the front lines, for I

honestly believe that is the only

way of beating off the attack.”

To

the general he went, and the order to

send up all the cars was confirmed.

Henderson, MacDowall, and Lucas-Shad

well were sent off post-haste, and

Smiles himself followed in a Ford. On

his way he saw Colonel Bolgramo at the

field telephone, and the colonel

signalled to him to stop.

“My

fellows have lost terribly,” he

said. “They cannot stand much more

of it. I want you to go right beyond

our barbed wire, and do what you can

to check the advance.”

The

Ford car used by Lieutenant Smiles was

in the nature of an improvisation. The

ordinary armoured car had often proved

too heavy for its purpose in districts

where the so-called roads were little

more than cart-tracks. When the force

was in Persia they found endless

difficulties in getting over the

ground where dust a foot deep lay on

the tracks, and it was soon driven

home to their minds that some lighter

form of car was essential in the East.

They conceived the idea of converting

an ordinary Ford car into an armoured

car by rigging steel plates round it,

and mounting in it a maxim with a

gun-shield. Thus the Ford armoured car

came into being, and proved very

useful for skirmishing, though of

course it could not take the same

risks as a “Lanchester“ or any of the

heavier cars. It was usually manned by

an officer, a driver, and a gunner -

sometimes only by driver and gunner,

and the latter very often lay on his

back, so as to get shelter from the

steel plates, and worked his gun in

that position.

Smiles

found that he could not get his car to

reverse, and therefore had to go into

action forwards. The disadvantage of

this is that the car has to be turned

round in order to get back again, and

on a narrow road turning is not an

easy process under any circumstances,

and is quite impossible if the car

refuses to reverse. There was,

however, no choice in the matter, so

he went full steam ahead past the line

of barbed wire, and was 500 yards

beyond it before he stopped. Then he

opened fire with his maxim at the

advancing Bulgarians and played havoc

with them. It is a queer sensation to

be stuck out in the midst of No Man's

Land, unsupported by friends, and a

conspicuous target for foes. It seems

that all the rifles, all the

machine-guns, and all the artillery

the enemy can muster are directed at

you and no one else. You seem to be

such a landmark for miles round that

you start wondering how the Hun's big

guns can possibly contrive to miss

you. At the same time you experience a

kind of exhilaration from the sense of

fighting an army single-handed, and

the sight of enemy infantry dropping

one after another, accompanied by the

sound of shells bursting all round

you, and the strident ha-ha-ha-ha of

your own machine-gun, has a curiously

stimulating effect. Life is so full of

crowded moments then that you lose

count of the passage of time, or

rather, you exaggerate the count, and

imagine that the space of a few

minutes has sent the clock round many

hours, for those few minutes contain

as much excitement as the majority of

people find in a whole life-time. All

the same, the officers in command of

an armoured car has little opportunity

to study these psychological effects,

for he has sooner or later to make up

his mind upon the chances of receiving

a direct hit by a shell. When the

artillery has crept up closer and

closer, so that the shells begin to

straddle him, he knows that the moment

has come to get a move on.

Now

Lieutenant Smiles had gone into action

nose forward because he could not get

his car to reverse. When he wanted to

come out of action, he found that the

road was too narrow to turn in, and

was bordered on either side by a

ditch. But hope springs eternal in the

human breast, and he had a vague

notion that the old car, which had

thrown its hand in when asked to

reverse into action, would be so jolly

glad to get out of it that it would

not only reverse, but would stand on

its head if necessary. So he told the

driver to try the reversing gear.

There was a grunt, a groan, and a

squeak; and then silence. The engine

had stopped. The silence, of course,

was only inside the car; outside it