|

Introduction

This

summary of the invasion and capture of Port Said

in November 1956 by Anglo-French forces is built

around the original London Gazette despatch

which is quoted in full in the right hand

column. As with other official despatches, this

one is short, to the point, accurate as far as

official secrecy and political expediency will

allow, and above all highly readable.

A

variety of background material appears in this

left hand column, mostly of a naval nature,

hopefully to give some additional colour to the

story. Sources of information are given where

appropriate, and as usual, Photo Ships has

provided most of the ship images.

No

comments are made on the political reasons for

invading Port Said after Egyptian President

Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal, nor on the

Anglo-French evacuation. What should perhaps be

pointed out is that a complex military campaign

involving two nations and three armed forces,

with little notice and limited resources, was

carried out successfully in a very short time,

and with few British and French casualties. As

always in such modern wars, civilian casualties

were heavy.

Contents

London

Gazette Despatch (right)

Events

in outline

Background

maps

Some

of the ships, aircraft and armour taking part

Casualties

British Honours and Awards

The

experience of Lt-Cdr James (Jim) Summerlee,

helicopter pilot, HMS Eagle

Other

sources

EVENTS

IN OUTLINE

"Operation

Musketeer" appears to apply to the joint

Anglo-French (Allied) and Israeli attempt to

wrest control of the Suez Canal out of Egyptian

hands, although it generally seems to be

associated with the invasion of Port Said and

planned advance along the Suez Canal:

1956

August

- Allied forces start to concentrate in Eastern

Mediterranean; planning and training continues

on in to October.

October

1956

29th

- Israel attacks across the Sinai.

30th

- Allied forces ordered to initiate Egyptian

operations leading to the occupation of Port

Said, Ismailia and Suez.

31st

- Allied air attacks, aimed at destroying the

Egyptian Air Force, are started by RAF bombers

late that afternoon.

31st/1st

November - south of Suez in the Red Sea, cruiser

HMS Newfoundland sinks Egyptian frigate Domiat

November

1956

1st -

Starting at daylight, Allied shore-based and

carrier aircraft continue to attack Egyptian

airfields

2nd

- By the end of the day, the destruction of

the Egyptian Air Force is all but complete,

although air attacks continue

5th

- Initial airborne assault by British

paratroopers to the west of Port Said and

French to the south.

6th

- Airborne drops continue, but it is now time

for the seaborne assault by RN helicopters

carrying Royal Marine commandos - the first

such major landing in history. As Port Said is

cleared, Allied forces reach El Cap,

23

miles south near to Al Qantara where they

stop. A UN-sponsored cease-fire is scheduled

for midnight.

December

1956

22nd

- The

evacuation of Anglo-French forces is

completed

BACKGROUND

MAPS

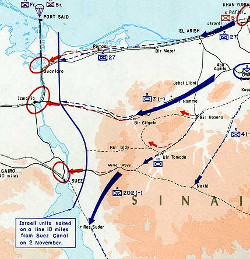

Israeli and

Anglo-French areas of operation

Israeli and

Anglo-French areas of operation

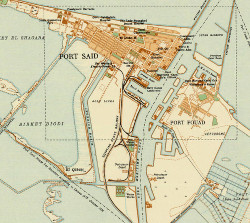

Port Said and northern end of Canal (Google)

More detailed map of Port Said, published 1936

(American Geographical Society Library). Changes

by 1956 are not known, but many of the

Port Said locations in the Despatch can be found

here. Gamil or El Gamil is 7km west of Port Said

on the Damietta coastal road. In the

enlargement, it is in the area of the green

patch at the top left.

Port

Said from the International Space Station, 2006,

north at bottom (Wikipedia)

SOME

OF THE SHIPS, AIRCRAFT AND ARMOUR TAKING

PART

Note:

FS is used unofficially for French warships

HMS

Tyne, depot/HQ ship

FS Lafayette, carrier

HMS Newfoundland, cruiser

FS Georges Leygues, cruiser

HMS Daring, destroyer

Egyptian frigate Domiat, sunk by

Newfoundland

HMS Anzio, LST. entering Malta

HMS Puncher, LST,

landing Centurion (Wikipedia)

Egyptian LST Akka scuttled in the Canal

British

Fleet Air Arm Sea

Venom

Egyptian, Russian-built Il-28 light bomber

in action against Israeli Forces in 1967

(Wikipedia)

Egyptian, Russian-built SU-100 tank

destroyer captured by 3 Para (Airborne

Forces Archive/Daniel Gent)

CASUALTIES*

ROYAL NAVY

with thanks to Don Kindell

6th

November 1956

Royal Marines, Suez War, Anglo-French

Invasion of Port Said, Egypt

40 Commando

DUDHILL, Lorin, Marine, RM 15070,

killed

FUDGE, Ronald J, Marine, RMV 202128,

killed

MCCARTHY, Peter W, Act/Lieutenant, RM,

killed in action

UFTON, Edward A, Act/Lieutenant, RM,

killed in action

42

Commando

DENNIS, Donald H A, Sergeant, RM,

PLY/X 4537, killed by sniper

HOWARD, David, Marine, RM 15145,

killed

PRICE, Bernard J, Marine, RM 11202,

killed

SHORT, Brian J, Marine, RM 11158,

killed

45 Commando

FOWLER, Michael J, Marine, RM 14245,

killed

GOODFELLOW, Cyril E, Marine, RM 13183,

killed

Note:Some

of the Royal Marines, from 45 Cdo, were

killed by "friendly fire" (Wikipedia). An

online account by Corporal(?) Colin

Ireland of 45 Cdo, who was badly wounded

in this attack confirms they were hit by

cannon fire from a single carrier-borne

Wyvern

as they went in to finish off an enemy

position that had just been strafed by

other Wyverns.

OTHER

Details

of other casualties have not been found.

Anglo-French totals are quoted in the

Despatch, but this is only believed to be

up to the cease-fire on the 6 November. It

appears that other Allied casualties

occurred after this date and up to the

Allied evacuation on the 22 December 1956

:

Britain

- 16 killed, 96 wounded

France

- 10 killed, 33 wounded

Egypt

- well in excess of 1,000 military

killed, a portion in action against the

Israelis in the Sinai desert

The

10 Royal Marines killed leaves six from

the other British services, of whom four

were lost with 3 Para (Paradata.org). This

would leave another two killed.

The Despatch lists two more British losses

- (1)

Lieutenant Moorhouse who was

kidnapped (but not recovered)

and (2) an officer of

the Scots Guards ambushed and killed

on the 16 December.

BRITISH

HONOURS and AWARDS

Recorded

in The London Gazette, issue

41092, 4th June 1957

ROYAL NAVY

Fourth Supplement to The

London Gazette

of Tuesday, 4th June, 1957

(Note:

repeating introductory text has been

removed; abbreviations substituted)

THURSDAY, 13 JUNE, 1957

CENTRAL

CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD.

St.

James's Palace, SWI

13th

June, 1957.

The QUEEN has been graciously pleased, on

the occasion of the Celebration of Her

Majesty's Birthday, to give orders for the

following promotions in recognition of

distinguished services in the Operations

in the Near East, October to December,

1956:

Royal

Navy and Royal Marine Officers

Order

of the Bath

Additional Member of the Military Division

of the Second Class, or Knight Commander

(KB)

Vice-Admiral Leonard Francis

DURNFORD-SLATER, CB

Order

of the British Empire

Knight Commander of the Military Division

(KBE)

Vice-Admiral Maxwell RICHMOND, CB, DSO,

OBE

Commanders of the Military Division (CBE)

Commodore Desmond Parry DREYER, DSC, RN

Captain Charles Piercy MILLS, DSC, RN

Captain Theodore Edward PODGER, RN, UK

Salvage Unit

Officers of the Military Division (OBE)

Captain Albert Victor BARTON, Master, RFA

Brown Ranger.

Major Basil Ian Spencer GOURLAY, MBE, MC,

RM, 3 Cdo Brigade, RM

Commander Edward Findley GUERITZ, DSC, RN

Lieutenant-Commander (then Acting

Commander) Lionel Geoffrey LYNE, DSC, RN,

HMS Forth

Commander William Charles SIMPSON, DSC,

RN, HMS Eagle

Members of the Military Division (MBE)

Lieutenant-Commander George Hill CREESE,

RN, HMS Eagle

Lieutenant-Commander John Homersham GOLDS,

RN, HMS Newfoundland

Lieutenant-Commander John Morris JONES,

RN, 895 RNAS

Lieutenant John Arthur Charles MORGAN, RN,

845 RNAS

Lieutenant-Comimander Eric Norman READ,

RN, HMS Kingarth.

Lieutenant-Commander Deryck Arthur Jaimes

SHEPPARD, RN, 810 RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander Alan Montagu Burleigh

TAYLOR, RN, HMS Eagle.

Royal Navy Ratings and Royal Marine

Other Ranks

British Empire Medal (Military Division) (BEM)

Chief Engine Room Artificer Ernest Walter

BASTIN, DSM, D/MX.54340, HMS Eagle

Acting Yeoman of Signals Reginald DAINTY,

P/JX.581680, HMS Chevron

Chief Aircraft Artificer Russell George

KING, L/FX.75251, 845 RNAS

Chief Petty Officer Cook (S) Royston

Leslie RUSSELL, P/MX.48443. HMS Armada

Chief Airman Harold Reuben Joshua SHOWELL,

L/FX.670678, HMS Albion

Chief Engine Room Artificer Joseph Eric

WHITENSTALL, DSM, P/MX.57728, HMS Bulwark

ADMIRALTY,

Whitehall,

SW1, 13th June. 1957.

The QUEEN has been graciously pleased, on

the occasion of the Celebration of Her

Majesty's Birthday, to give orders for the

following appointments to the

Distinguished Service Order and to approve

the following awards in recognition of

gallant and distinguished services in the

Operations in the Near East, October to

December 1956:

Royal

Navy and Royal Marine Officers

Distinguished

Service Order

Brigadier Reginald William MADOC, OBE. RM,

3 Commando Brigade, RM

Lieutenant-Colonel David Gratiaen TWEED,

MBE, RM, 40 Cdo. RM,

Bar to

the Distinguished Service Cross

Lieutenant-Commander Maurice William

HENLEY, DSC, RN, 893 RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander

Peter Melville "Sheepy" LAMB, DSC, AFC,

RN, 810 RNAS (Sqdn CO) (see

below)

Distinguished

Service Cross

Lieutenant-Commander Eric Charles DAY, RN,

HMS Forth.

Lieutenant-Commander Royston Leonard

EVELEIGH, RN, 802 RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander Charles Vyvyan

HOWARD, RN 830 RNAS.

Bar to

the Military Cross

Major Dennis Leolin Samuel St. Maur

ALDRIDGE, MBE, MC, RM, 42 Cdo, RM,

Military

Cross

Major Anthony Patrick WILLASEY-WILSEY.

MBE, RM, 40 Cdo, RM,

Captain Michael Anthony Higham MARSTON,

RM, 40 Cdo, RM,

Lieutenant Stuart Lawrence SYRAD, RM, 45

Cdo, RM

Royal

Navy Ratings and Royal Marine Other

Ranks

Distinguished

Conduct Medal

Corporal Douglas Edward MANT, PO.X.2992,

RM, 40 Cdo, RM

Distinguished

Service Medal

Leading Seaman Thomas DYER, P/JX.163578,

HMS Newfoundland.

Able Seaman Roy Joseph LOADER.

D/JX.912011, HMS Crane.

Military

Medal

Quartermaster Sergeant George Desmond

BUTTERY, PO.X.4096, RM, 40 Cdo, RM

Corporal Michael Edward MEAD, RM11157, RM,

45 Cdo, RM

Marine James Willie CROSSLAND, RM14422,

RM, 40 Cdo, RM

Marine David Kelly DAVIDSON, RM14644. RM,

45 Cdo, RM

Mention

in Despatches

Royal

Navy Officers

Captain John Graham HAMILTON, RN, HMS

Newfoundland

Commander Ian David MCLAUGHLAN, DSC. RN,

HM.S. Chevron

Lieutenant-Commander Peter Everard BAILEY,

RN, HMS Eagle.

Lieutenant-Commander Arthur Bernard Bruce

CLARK, RN, 899 RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander Derek Arthur FULLER,

RN, 849C (sic) RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander Brian Haviland

HARRISS, RN, HMS Albion

Lieutenant-Commander Antony Herbert Lane

HARVEY, DSC, RN, HMS Bastion

Lieutenant-Commander Timothy Francis

HEGARTY, RN, HMS Crane

Lieutenant-Commander John Claud JACOB, RN,

845 RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander Randal von Tempsky

Bernau KETTLE, RN, 804 RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander David Thomas MCKEOWN,

RN, 802 RNAS.

Lieutenant-Commander Malcolm Harold James

PETRIE, RN, 892 RNAS

Lieutenant-Commander Alfred Raymond

RAWBONE, AFC, RN, 897 RNAS

Lieutenant-Commander John Desmond RUSSELL,

RN, 800 RNAS

Lieutenant-Commander Ronald Arthur

SHILCOCK, RN, 809 RNAS

Lieutenant-Commander James

Henry SUMMERLEE, RN, HMS Eagle (see

below)

Lieutenant-Commander Maurice Arthur TIBBY,

RN, 800 RNAS

Lieutenant-Commander Kenneth

ALAN-WILLIAMS, RN, HMS Portcullis

Lieutenant Ian Bruce LENNOX, RN, HMS

Sallyport

Lieutenant Harry PARKER, RN, HMS Lofoten.

Surgeon Lieutenant John Gwyther BRADFORD,

MB, BS, RN, 45 Cdo, RM,

Acting Surgeon Lieutenant Peter Gordon

HARRIES, MB, BS, RN, HMS Diana.

Sub-Lieutenant (SD) Frank Alexander JUPP,

RN, HMS Newfoundland.

Royal Marine Officers

Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Lawrence NORCOCK,

OBE, RM, 42 Cdo, RM

Lieutenant-Colonel Norman Hastings

TAILYOUR, DSO, RM, 45 Cdo, RM (father

of Major Ewen Southby-Tailyour who

played an important role in the 1982

Falklands War)

Major Richard Dennis CROMBIE, RM, 45 Cdo,

RM

Captain Hamish Brian EMSLIE, MC, RM, 42

Cdo, RM

Captain Jesse Hotchkiss HAYCOCK, RM, 45

Cdo, RM

Captain Richard Francis Gerard MEADOWS,

MBE, RM, 45 Cdo, RM

Captain Frederick Roy SILLITOE, RM, 42

Cdo, RM

Lieutenant (Local Captain) Terrance John

WILLS, RM, 42 Cdo, RM

Lieutenant Rudolph Douglas EDWARDS, RM, 40

Cdo, RM

Lieutenant Timothy John Michael WILSON,

RM, 40 Cdo, RM

Acting Lieutenant Anthony William

RICHARDSON, RM, 45 Cdo, RM

Acting Lieutenant Alistair Dunlop RODGER,

RM, HMS Striker

Royal Navy Ratings

Chief Petty Officer Robert Alec COKES,

P/JX.151267, HMS Chaplet

Chief Petty Officer Telegraphist William

Heron CHISHOLM, DSM, C/JX.142524, HMS

Jamaica.

Chief Engine Room Artificer John James

SEYMOUR, P/MX.52269, HMS Chaplet

Chief Engine Room Artificer Sidney George

WARD, P/MX.56545, HMS Woodbridge Haven

Chief Engineering Mechanic Charles James

SALMON, P/KX.91789, HMS Newfoundland

Chief Electrician Gordon Enderson MORRIS,

D/MX.856466, HMS Eagle

Chief Radio Electrical Artificer George

Haslam WHITTAKER, P/MX.715767, HMS Duchess

Chief Aircraft Artificer Charles Henry

BERRY, L/FX.75018, 892 RNAS

Chief Aircraft Artificer Leonard CARTER,

L/FX.87518, 895 RNAS

Chief Aircraft Artificer Francis Newton

DAVIS, L/FX.76919, 804 RNAS

Chief Aircraft Artificer Patrick Joseph

FOLEY, L/FX.766096, 802 RNAS

Chief Aircraft Artificer Hugh Charles

Cecil HUZZEY, L/.FX.76704, 810 RNAS

Chief Airman Charles Henry FRENCH,

L/FX.857897, HMS Eagle

Aircraft Artificer (O) 1st Class Dennis

HARBIN, L/FX.935430, 895 RNAS

Chief Aircraft Mechanician Reginald Arthur

WILSON, L/FX.75690. 800 RNAS

Sick Berth Chief Petty Officer Joseph

Windsor BENNETT, P/MX.53428, HMS Theseus

Sick Berth Chief Petty Officer Thomas

Arthur GRUNDY, D/MX.49569, HMS Ocean

Chief Petty Officer Cook (S) Claude Henry

BELL, P/MX.52864, HMS Albion

Master-at-Arms Albert Charles NICHOLLS,

P/MX.716378, HMS Tyne

Petty Officer Clifford JAMES, P/JX.801647,

HMS Duchess

Yeoman of Signals George Thomas Warren

RYRTE, D/JX.156879, HMS Manxman

Petty Officer Telegraphist Ronald Joseph

GARRAD, P/JX.712711, HMS Newfoundland

Petty Officer Writer Bernard THOMPSON,

C/MX.849428

Leading Airman Kenneth Edward GAMMER,

L/EX.906108, HMS Eagle.

Leading Airman George James Henry HAZEL,

L/FX.886965, HMS Eagle

Leading Sick Berth Attendant Terence

Francis JENNINGS, D/MX.896612,

HMS Crane.

Naval Airman 1st Class Anthony Brian

WEBSTER, L/FX.917498, HMS Eagle

Sick Berth Attendant Brian Anthony

GREENACRE, D/MX.923667, HMS Eagle

Sick Berth Attendant Stanley George

LlNDFIELD, P/M.932119, HMS Newfoundland

Royal Marine Other Ranks

Sergeant Arthur Henry HOWARTH, Ply.X.5512,

RM, HMS Striker

Sergeant Arthur Thomas George PECK,

Ch.X.5357, RM, 40 Cdo, RM

Sergeant Ernest James SIM, Ch.X.4768, RM,

45 Cdo, RM

Corporal Peter Shand YOUNG, RM.9957, RM,

42 Cdo, RM

Marine John Albert Windsor COX, RM.15050,

RM, 40 Cdo, RM

Marine Alan William MIDDLETON, Po.X-6406,

RM, 42 Cdo, RM

Marine Ronald Frederick SAGGERS,

Po.X.6552, RM, 42 Cdo, RM

OTHERS

For

British Army and Royal Air Forces

Honours and Awards, go to The London

Gazette, issue 41092, 4th June 1957

Any British awards to French servicemen

have not been identified

Analysis of British Gallantry Awards

by Ship/Unit

Additional

Source: The Naval Review, 1957/2

for RNAS Squadrons

COMMAND AND STAFF(?)

Naval Task Force Commanders (2),

KB, KBE

Staff? CBEx2, OBE x 1

PO Writer - staff?,

MID

ROYAL NAVY WARSHIPS

Aircraft Carriers

HMS Albion, BEM, MIDx2 (Seahawk Sqdns

800 & 802, Sea Venom Sqdn 809,

Skyraider Flt from

849)

HMS Bulwark, BEM (Seahawk Sqdns 804,

810, 895)

HMS Eagle, OBE, MBEx2, BEM, MIDx8

(Seahawk Sqdns 897 & 899, Sea

Venom Sqdns 892 & 893, Wyvern Sqdn

830, Skyraider Flt from 849)

Commando-carrying Carriers (845 RNAS,

Whirlwind HAS.22 helicopters)

HMS Ocean, MID

HMS Theseus, MID

Cruisers

HMS Jamaica, MID

HMS Newfoundland, MBE, DSM, MIDx5

Minelayer

HMS Manxman, MID

Destroyers

HMS Armada, BEM

HMS Chaplet, MIDx2

HMS Chevron, BEM, MID

HMS Diana, MID

HMS Duchess, MIDx2

Sloop

HMS Crane, DSM, MIDx2

Depot/HQ Ships

HMS Forth, OBE, DSC

HMS Tyne, MID

HMS Woodbridge Haven, MID

Landing Ship's Tank

HMS Bastion, MID

HMS Lofoten, MID

HMS Portcullis, MID

HMS Sallyport, MID

HMS Striker, MIDx2

Coastal Salvage Vessel

HMS Kingarth, MBE

OTHER VESSELS/UNITS

Royal Fleet Auxilliary

RFA Brown Ranger, OBE

UK Salvage Unit

CBE

FLEET AIR ARM NAVAL SQUADRONS

800 RNAS, MIDx3 (Albion, Seahawk Sqdn)

802 RNAS DSC, MIDx2 (Albion,

Seahawk Sqdn)

804 RNAS, MIDx2 (Bulwark, Seahawk Sqdn)

809 RNAS, MID (Albion, Sea Venom

Sqdn)

810 RNAS, MBE, DSC*, MID (Bulwark,

Seahawk Sqdn)

830 RNAS, DSC (Eagle, Wyvern Sqdn)

845 RNAS MBE, BEM, MID (Ocean &

Theseus, Whirlwind HAS.22 helicopters)

849C RNAS, MID (Eagle, Skyraider Flt;

also Albion, 1 Flt)

892 RNAS, MIDx2 (Eagle, Sea Venom Sqdn)

893 RNAS, DSC* (Eagle, Sea Venom

Sqdn)

895 RNAS, MBE, MIDx2 (Bulwark, Seahawk

Sqdn)

897 RNAS, MID (Eagle, Seahawk Sqdn)

899 RNAS, MID (Eagle, Seahawk Sqdn)

ROYAL MARINE 3 COMMANDO BRIGADE

3

Cdo Brigade, RM, DSO, OBE

40 Cdo, RM, DSO, MCx2, DCM, MMx2, MIDX4

42 Cdo, RM, MC*, MIDx7

45 Cdo, RM, MC, MMx2, MIDx7

Note:

the ships listed above are only a small

proportion of the numbers taking part

A

PERSONAL TALE

The

Experience of Lt-Cdr James (Jim)

Summerlee, rescue helicopter pilot, HMS

Eagle

"HMS

Eagle, dated 28 August 1956, The

Helicopter Rescue Unit.

seated centre - Pete Ragley, Jim, and

Chief 'Duff Cooper'"

After an accident

in the mess, transferred to RNAS Gosport on 17

April 1952 for training on Sikorsky S51

helicopters. First posting was to HMS Vulture,

RNAS St Merryn, Cornwall, as a SAR (Search and

Rescue) pilot for 4 or 5 months.

On the 9 Nov 1953, he was loaned to the Royal

Australian Navy and served on HMAS Sydney in

the Korean War theatre on SAR. He flew out in

a Constellation, joined Sydney in Singapore,

and returned home at the end of hostilities

from Singapore to Stanstead in Essex in an

Avro York. While out in the Far East, he

travelled by boat from Kure, Japan to visit

Hiroshima.

After leave, posted to HMS Seahawk, RNAS

Culdrose in June 1954 as search & rescue

pilot. Following a quick conversion

course to Sikorsky S55's at HMS Daedalus, RNAS

Lee-on-Solent, he was posted to fleet

carrier HMS Eagle on 6 February 1956 as

Commanding Officer of the Search & Rescue

unit. During this time, Eagle took part in the

Suez Campaign, and Jim received two

Commendations. One, to the whole crew was from

the Commander-in-Chief for rescuing Lt. Lyn

Middleton (who

commanded carrier HMS Hermes in the 1982

Falklands War and later went on to become an

admiral). The second was a Mention in

Despatches for flying in and out of the War

Zone at Suez, taking in medical supplies and

bringing out the wounded. Jim lifted out Lyn

Middleton on a second occasion, and narrowly

missed doing so on a third. That was off the

south coast of Malta when the resident crew at

Halfar did the job.

Rear Admiral Power, F.O.A.C. - "A Man we

all Admired" (Sir Manley, KCB, CBE,

DSO*, commanded 26th Destroyer Flotilla

which sank Japanese heavy cruiser Haguro

in May 1945, promoted Rear Admiral 1953,

Flag Officer Aircraft Carriers 1956-57)

Rear Admiral Power, F.O.A.C. - "A Man we

all Admired" (Sir Manley, KCB, CBE,

DSO*, commanded 26th Destroyer Flotilla

which sank Japanese heavy cruiser Haguro

in May 1945, promoted Rear Admiral 1953,

Flag Officer Aircraft Carriers 1956-57)

HMS

Eagle and rest of "our Carrier Air

Group"

(possibly Albion and Bulwark)

G.O.C. Cyprus and the Captain, The

Maclean of Maclean, (unidentified)

HMS Eagle - speed trials

HMS Eagle - speed trials

Jim

ranging a helo at Malta, Captain

Maclean on lift

Jim

ranging a helo at Malta, Captain

Maclean on lift

HMS Eagle,

dated 14 June 1956. Piloted by Jim

Summerlee, with crewmen Mitchell and

Hazel (testing winch) off Cyprus. Note

side arms.

HMS Eagle,

dated 14 June 1956. Piloted by Jim

Summerlee, with crewmen Mitchell and

Hazel (testing winch) off Cyprus. Note

side arms.

"How do you do? Shaggers & Sheepy

(Lamb)"

(two of Jim's oppos in the early 1950's

on HMS Vengeance. "Sheepy" was awarded a

second DSC at Suez)

and from

"Crises

Do Happen: the Royal Navy and

Operation Musketeer, Suez, 1956" by

Geoffrey Carter, Maritime Books, 2006

"Following

a Wyvern bombing attack on the fortified

Coastguard Station at Port Said during the

Suez campaign:

'Lt Cdr Bill Cowling, recognising that his

aircraft had been hit (by flak), climbed

to 1200 feet but had to throttle back.

Eagle having acknowledged his Mayday call,

Cowling ejected from his Wyvern some five

or six miles from Port Said. As he landed

in the sea, a Whirlwind helicopter, flown

by Lt Cdr Jim Summerlee, was nearby

transporting wounded soldIers back to the

carrier. Cowling was quickly hauled aboard

and, although he had to stand up for the

journey, was soon back aboard Eagle.'"

(page 31)

OTHER SOURCES

Apart

from a variety of internet sites, a number

of specific sources on the Royal Navy in

Operation Musketeer have been found. They

are listed in order of publication date:

Suez,

1956, Operation Musketeer by

Robert Jackson, 1980

Crises

Do Happen: the Royal Navy and

Operation Musketeer, Suez, 1956

by Geoffrey Carter, 2006

Suez, 1956: A Successful Naval

Operation Compromised by Inept

Political Leadership by Michael

H Coles, 2006, PDF download from

US Naval War College site

Operation Musketeer - the Suez

Canal Crisis of 1956: The

Stories and Photographs from

Those Who Were There, by Eric

Pegg, 2013

|

|

|

|

Recorded

in The London Gazette, issue 41172, 10th

September 1957

General

Keightley, C-in-C (Wikipedia)

The Ministry of Defence,

12th September, 1957

DESPATCH BY

GENERAL SIR CHARLES F. KEIGHTLEY, GCB., GBE.,

DSO.,

COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF, ALLIED FORCES

OPERATIONS IN

EGYPT—NOVEMBER to DECEMBER, 1956

The following despatch describes the operations

in the Eastern Mediterranean from 30th October,

1956, when orders were issued by Her Majesty's

Government to be prepared in certain

circumstances to initiate operations in Egypt

until 22nd December, 1956, when evacuation was

completed. I am forwarding certain detailed

recommendations on specific organisational

tactical and technical matters separately.

ONE

Background

On 11th August, 1956, in the appointment of

Commander-in-Chief of the British Middle East

Land Forces, I was informed that, in view of

Egypt's action in nationalising the Suez Canal,

Her Majesty's Government and the French

Government had decided to concentrate certain

forces in the Eastern Mediterranean in case

armed intervention should be necessary in order

to protect their interests and that in this

event I was to assume the appointment of Allied

Commander-in-Chief of all British and French

Forces engaged.

In my capacity as

Commander-in-Chief Middle East Land Forces I

had already been engaged in planning for

possible operations in the area but mainly in

the event of Britain being involved as a

result of her commitments through the

Anglo-Jordanian Alliance.

It was now necessary to consider

specifically what action should 'be taken

against Egypt if her seizure of the Canal

should result in hostilities.

The following forces were earmarked by the

British and French Governments should

operations prove to be necessary: —

BRITISH

Naval

Aircraft

Carrier Task Group

Support Forces Group, including Cruisers,

Darings, Destroyers and Frigates

Minesweeping Group

Amphibious Warfare Squadron

Land

16 Independent

Parachute Brigade Group (including 1, 2

& 3 Para)

3 Commando Brigade, Royal Marines (including

40, 42 & 45 Cdo)

10 Armoured Division

3 Infantry Division

Medium and

Light Bomber Force

Fighter/Ground Attack Force, shore-based and

carrier-borne

Reconnaissance and Transport and Helicopter

Forces

FRENCH

Naval

Aircraft Carrier

Task Group

Support Forces Group, including 1 Battleship,

Cruisers, Destroyers and Frigates.

Minesweeping Group

Land

10 Division

Aeroportee

7 Division Mecanique Rapide

Air

Fighter/Ground

Attack Force, shore-based and carrier-borne

Reconnaissance and Transport Forces

The following Commanders were nominated to draw

up plans and to assume command in the event of

operations :—

Vice-Admiral

D'Escadre P. Barjot - Deputy

Commander-in-Chief

Vice-Admiral M. Richmond, CB., DSO., OBE. -

Naval Task Force Commander (Succeeded by

Vice-Admiral D. F. Durnford-Slater, CB., on

24th October, 1956).

Contre-Amiral P. Lancelot - Deputy Naval Task

Force Commander

Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Stockwell, KGB.,

KBE., DSO. - Land Task Force Commander

General de Division A. Beaufre - Deputy Land

Task Force Commander

Air Marshal D. H. F. Barnett, CB., CBE., DFC.

- Commander Air Task Force

General de Brigade R. Brohon - Deputy

Commander Air Task Force

I formed a small Allied Headquarters in London

and similarly Task Force Commanders built up

their Headquarters which were also located in

London.

Owing to the Forces concerned being located as

far apart as the United Kingdom, Malta, Cyprus,

France and Algiers, and my Headquarters being

split between London and Cyprus a great deal of

travelling was required by all Commanders.

Throughout August and September plans were made

to take action in Egypt if some crisis should

occur to demand our intervention. These plans

were necessarily flexible as it could not be

foreseen precisely in what circumstances it

might be necessary to intervene.

Whatever action was required by us would however

clearly require airborne and sea assault

operations and the British and French Airborne

Forces and Commandos were prepared and trained

for such action.

The main limitations to our operations were

caused by the following factors: —

1. Lack of

harbours or anchorages or landing craft

"hards" in Cyprus: thereby necessitating any

seaborne assault being launched from Malta,

which was over 900 miles away.

2. Shortage of airfields in Cyprus. At

the outset of the planning only Nicosia was in

operation and that was under reconstruction

and not working to full capacity. Akrotiri and

Tymbou were developed rapidly during September

and October.

3. Limited resources of landing craft

and air transport We had only a total of 18

LST's and 11 LCT's. We had an air lift for two

battalions but very limited air supply

resources.

TWO

Early in October I was instructed to recast our

current plans so that action could if necessary

be taken any time during the winter months.

This had wide repercussions.

Men could not be kept for long stretches at a

number of hours notice to move, and in view of

the prolonged period that the call up had lasted

it was especially desirable to send reservists,

who had been called up at very short notice, on

leave.

Certain vehicle ships had to be unloaded as some

of the vehicles had been loaded for as much as

three months and batteries and equipment were

deteriorating so much that they were unlikely to

be able to start on landing. In addition there

was a danger from petrol fumes in the loaded

ships.

A stockpile of supplies was built up in

Cyprus but even so owing to the limited port

resources the majority of ships for the

follow-up and supply for the assault troops must

come from the United Kingdom. This demanded

ships which it was quite impossible economically

to hold loaded for a long stretch being

requisitioned and sailed to the Eastern

Mediterranean.

Neutral shipping in and approaching the Suez

Canal would have to be diverted before any

operations could take place.

Up-to-date intelligence was required of Egyptian

preparations and land and air dispositions. This

would necessitate photographic reconnaissance

over the area of assault and the airfields.

Action would be necessary and was planned to

evacuate the British contractors working in the

Suez Base.

Weather would be deteriorating and emphasised

the time required to sail the assault landing

craft from the nearest harbour where they could

be held, at Malta, to Port Said.

The effect of these factors was to make a

requirement for a longer period between the

executive order to start operations being

received and the date it was possible to land on

the mainland of Egypt.

The period of notice which had been accepted for

the start of operations was 10 days, although in

the event we got little more than 10 hours.

Exercises

One of our greatest problems was to train and

exercise the troops and Headquarters involved

for the task which lay ahead, owing to the

immense dispersion of the forces, involved.

The forces in the United Kingdom were

concentrated on Salisbury Plain and at their

home stations and certain useful unit training

was carried out

Landing exercises were carried out with the

Commandos and 6th Royal Tank Regiment at Malta.

It was in the Command and control field and

especially with regard to Signal exercises where

we were most handicapped and it is a great

credit to all the Headquarters and Signal staffs

that in the event communications worked so well.

Early in October Task Force Commanders had

pressed for a Command Signal Exercise in

particular to exercise the Headquarters ship.

This exercise, called Exercise Boathook, was

agreed in October and planned to take place

early in November; in the end it never took

place.

Israeli

Mobilisation

During the last week in October intelligence

sources were reporting from Tel Aviv and

elsewhere increasingly strong indications of

Israeli mobilisation. As a result of these

reports certain precautions were taken as

regards the preparedness of our forces.

On October 29th Israel attacked across the Sinai

Peninsula.

THREE

Situation on 30th October

On 30th October I was informed that Her

Majesty's Government were issuing a requirement

to Israel and Egypt : —

(a) to cease

hostilities by land, sea and air;

(b) to withdraw contestant troops ten miles

from the Suez Canal;

(c) to allow occupation by Anglo-French Forces

of Port Said, Ismailia and Suez.

I was to be prepared to take action on 31st

October in the event of this requirement not

being met by either country.

It was therefore clear that instead of 10 days

interval between the executive order and the

start of operations I was liable to get about 10

hours, and our operations might well be quite

different to those for which we had planned.

There was much to be done.

Of the many immediate steps to be taken the most

important were:—

(a) To complete

the preparedness of the Allied Air Force.

(b) To embark and sail the British Assault

Force from Malta and the French Assault Force

from the Westbrn Mediterranean.

(c) To embark and sail the immediate follow-up

forces from Malta, the Western Mediterranean

and the United Kingdom.

(d) To open up all Command Signal nets between

my Allied Force Headquarters, Task Force

Headquarters and formations.

Allied Forces were then located as follows: —

NAVAL FORCES

British and French Naval Forces were then in the

general area of the Central Mediterranean.

LAND FORCES

British

16 Independent

Parachute Brigade in Cyprus.

3 Commando Brigade and 6 Royal Tanks in Malta.

10 Armoured Division in Libya.

3 Infantry Division in the United Kingdom.

French

10 Division

Aeroportee partly in Cyprus.

7 Division Mecanique Rapide in Algeria.

AIR FORCES

British

Bomber force in

Cyprus and Malta.

3 Ground attack squadrons in Cyprus.

French

2 Ground attack

squadrons in Cyprus.

FOUR

The Plan of Operations

At 0430 hours 31st October I was informed that

the Israeli Government had agreed the

requirement and that Egypt had refused.

My object was defined as follows: —

(i) To

bring about a cessation of hostilities between

Israel and Egyptian forces.

(ii) To interpose my forces between those of

Israel and Egypt.

(iii) To occupy Port Said, Ismailia and Suez.

The agreement to our requirements by the

Israelis and the refusal by the Egyptians meant

that we were now involved in operations against

the Egyptians but with limited objectives.

My instructions were that air operations against

the Egyptians would start on 31st October.

My estimate of the Egyptian strength at this

time was as follows, not taking into account

such forces as were known to have been engaged

in the Sinai Peninsula: —

Egyptian Air

Force

80 MIG 15's

45 IL 28 bombers

25 Meteors

57 Vampires

200 trainers, communication and transport

Egyptian Army

75.000 Infantry

300 tanks which included over 150 modern

Russian tanks (JS 3's, T 34's and T 85's).

An unknown number of self-propelted anti-tank

guns, including the modern Russian SU 100's.

A considerable number of anti-aircraft guns and

a modern radar organisation.

My main concern was naturally that of speed.

Certain parts of the previous plans could fit in

with the operation which I was now required to

carry out; certain of them could not.

The limiting factor was clearly the Commando and

armour located at Malta. As a result of previous

preparedness and excellent work by all officers

and men they were embarked on the night 30/31st

October and directed to sail at full speed for

Port Said, a distance of 936 miles by the

shortest route. At the maximum speed of the

landing craft this trip must take 6 days.

The aircraft carriers and HQ ships had been

assembling in the Central Mediterranean for

Exercise Boathook. This was in some ways an

advantage and in some ways a disadvantage.

Although it resulted in ships being reasonably

concentrated they could not be briefed

personally or easily for the operations in hand.

The Royal Air Force were the most easily

prepared for action. It was clearly necessary to

eliminate the threat of Egyptian air effort from

being able to engage our landing craft as they

sailed from Malta along the Egyptian coast or

our air transports from Cyprus as they

approached their dropping zones. Further, any

action by the IL.28 bombers against our

overcrowded airfields in Cyprus would have done

damage out of all proportion to the effort

involved.

Although the effectiveness of the Egyptian Air

Force was never overestimated, they had been in

action against the Israeli forces and they had

foreign technicians who were certainly capable

of carrying out missions on the Korean pattern.

So my first objective was the Egyjptian Air

Force.

The plan for this was a combination of high

level bombing with contact and delay action

bombs to damage runways and discourage aircraft

from taking off. This to be followed by daylight

ground attacks.

It was estimated this would take 48 hours to

complete.

The next problem was when to use our airborne

forces.

We had a limited airborne effort but in

particular our air supply lift and air supply

resources were very restricted. The offensive

power we had against the Egyptian anti-aircraft

guns was from the Fleet Air Arm and fighters

from Cyprus, the time over target of the latter

being limited to ten to fifteen minutes.

My final objective at this stage it may be

remembered was Suez. My problem was therefore to

prevent the Egyptians moving any of their

armoured forces, which were concentrated in

reserve, to the Canal Zone and especially on to

the Causeway, that narrow strip of sand at

places only a few hundred yards wide, on which

the road runs from Port Said to Ismailia. Here

even a few tanks might have caused a physical

block which would have taken a very considerable

time to clear. We hoped to do this by keeping

them uncertain until the last moment whether our

main attack was to be at Port Said or

Alexandria. This, in fact, we succeeded in

doing.

It was therefore decided to employ the airborne

forces early enough to facilitate a quick run

through of the armour but to avoid using them

piecemeal whereby they might become immobilised.

Weather was also a factor to be reckoned with.

At this time of year weather can deteriorate

very suddenly and very seriously.

Apart from the start of air operations, the

speed of operations was dictated solely by local

factors. It was estimated that we would land our

assault forces from Malta by November 6th, have

seized Ismailia by November 8th and Suez by

November 11th. That would have completed the

whole operation in 12 days from the start of air

operations.

FIVE

The Operation

At 1615 hours GMT on 31st October, 1956, Valiant

and Canberra bombers under the command of Air

Marshal Barnett began their attacks on Egyptian

airfields at Almaza and Inchas near Cairo and at

Abu Suier and Kabrit in the Canal Zone. These

attacks were continued with the aid of flares

during the early part of the night and

encountered a certain amount of anti-aircraft

fire but no night fighters.

We had an anxious moment when I was instructed,

after the aircraft had taken off on their first

mission which included Cairo West Airfield, not

to attack that airfield, since information had

been received that American Nationals were being

evacuated to Alexandria and were using the road

close to the airfield. Since Cairo West was a

main bomber base for the Russian made IL 28's

its sudden reprieve was a matter of concern.

However, in the event, the Egyptians only used

it to remove their IL 28's to Luxor.

I was also instructed to be prepared to attack

Cairo Radio later after issuing warnings so as

to avoid civilian casualties.

During the night HMS Newfoundland encountered

the Egyptian Frigate Domyat in the Red Sea and

sank her after she had failed to reply to a

signal: 68 survivors were picked up.

From daylight onwards Allied shore-based and

carrier aircraft carried out highly successful

attacks on aircraft on Egyptian airfields while

French naval aircraft set fire to a

Russian-built destroyer off Alexandria.

Two attempts were made to sink the old LST Akka

which had been identified as a prepared

blockship. Anchored in shallow water in Lake

Timsah she was well placed for towing into the

narrow channel at the southern end of the lake.

Unfortunately the attacks were only partially

successful and before the ship could be sunk she

had been towed in a sinking condition to her

blocking position. In view of the subsequent

orgy of sinking carried out by the Egyptians the

relative importance of the Akka assumed far less

significance than seemed likely at the time.

By the end of the day the Egyptian Air Force had

been severely treated: a large number of

aircraft had been destroyed or damaged on the

ground and very few appear to have been

airborne. Only one of our aircraft had been

attacked in the air and suffered slight damage,

while others had incurred minor damage from

anti-aircraft fire.

During the night, bomber attacks from Cyprus and

Malta were kept up against Egyptian airfields

followed up by ground attacks by naval and shore

based aircraft from first light onwards on 2nd

November. Later in the day these attacks were

made on Huckstep Camp, which contained many

armoured fighting vehicles and large quantities

of military transport, and on Almaza Barracks,

also a military concentration area.

Cairo Radio was then attacked during the morning

by a force of Canberras with top cover provided

by French fighters. Bombs were dropped on the

Radio Masts of the transmitter station which are

some 16 miles from the town, after warnings had

been given by the Voice of Britain Radio in

Cyprus. After the attack the short wave

transmitters of Cairo Radio went off the air and

the Voice of Britain operated on the Cairo

wavelength. This attack was only partially

successful but by the time the damage had been

repaired and the short wave transmissions of

Cairo Radio had been fully resumed a cease fire

had come into effect.

During the day air reconnaissance disclosed the

first signs that the Egyptians were carrying out

extensive blocking of the Canal. Ships were seen

sunk across the entrance to Port Said and

another ship was seen sunk near El Firdan.

By the end of 2nd November it was evident that

the task of neutralising the Egyptian Air Force

was all but complete. A number of IL 28's still

remained untouched on Luxor airfield which was

attacked during the night 2-3rd November and on

4th November.

During 3rd November the bulk of the air effort

was switched from airfields to other military

targets. Huckstep Camp and Almaza Barracks were

again attacked, as was the marshalling yard at

Ismailia with the object of slowing up any

reinforcement of Port Said by rail. The above

utilised a small part only of our available air

effort, but lack of suitable targets in areas

away from the civilian population, whose safety

was from the outset one of our primary concerns,

materially restricted their activities. The use

of the bomber was in fact to be discontinued and

their last attack was an attempted raid on the

guns and submarine base at Agami Island off

Alexandria on the night of 3-4th November. The

attack was intended primarily to attract

attention away from Port Said.

The main air effort from now onwards was

directed against the very heavy military

movement in the Canal area. Armed reconnaissance

missions found much military transport and

considerable numbers of tanks. These were

heavily intermixed with civilian vehicles of all

descriptions and many military targets had to be

discarded by pilots for this reason.

It is interesting to record the behaviour of all

these vehicles on the arrival of our aircraft.

In general military crews abandoned their

vehicles, whereas the civilian traffic proceeded

unperturbed. This speaks highly for the

integrity of our aircrew and the complete trust

in our frequently broadcast intentions of

attacking only military objectives. Similar

behaviour had been reported during our air

attacks on airfields, when pilots reported that

the only military activity seen was from

antiaircraft guns but that numbers of spectators

watched their activities from the perimeter of

the landing ground. The same undisturbed public

interest was later to be reported from Port Said

in the course of the assault.

On the 3rd and 4th November air attacks were

directed at armoured concentrations and military

movement on the roads. Photographic

reconnaissance of the Port Said beaches and

defences was completed. This showed that the

Egyptians were prepared to defend the town and

the beaches and that there were considerable

numbers of anti-aircraft guns in position and

some dug-in tanks. Mines were also seen on the

beaches. Nasser had already announced his

intention of concentrating to fight the Allies

and there was every indication that preparations

were being made accordingly.

As a result of our latest information on

Egyptian defences and dispositions, the weather

forecast and the progress of the assault force

from Malta, I confirmed with the Task Force

Commanders that we should carry out an airborne

assault on the Port Said area on the 5th

November.

It was accordingly planned to drop at first

light on 5th November one British Parachute

Battalion on Gamil airfield, West of Port Said,

and one French Parachute Regiment in two

echelons, firstly on the Southern exits from

Port Said and secondly on the Southern end of

Port Fuad. The British force was to advance into

the town and occupy it if resistance was slight

but if unable to do so it would wait for the

seaborne assault on the following day. To this

end Allied shore based and carrier aircraft

attacked all military road movement and

concentrations of tanks and vehicles, as well as

coast defences and anti-aircraft gun sites

around Port Said, the greatest care being taken

throughout to avoid damage to civilian property.

During 4th November Lieutenant-General Stockwell

and Air Marshal Barnett joined Vice-Admiral

Durnford-Slater in H.M.S. Tyne and sailed from

Cyprus together with the seaborne support troops

for both the British and French parachute

operations.

The sea convoys from Malta and Algiers were also

converging on Port Said, the weather was good.

Anxiety was caused by the activities of the U.S.

Sixth Fleet which, since 31st October, had been

moved to and stationed in the same operating

areas as our own carriers, in order to provide

protection for the evacuation of U.S. nationals

from Alexandria and the Levant. Despite the very

real difficulties created by this situation and

the great inconvenience experienced by our

forces, thanks to the good sense of the two

naval commanders both were able to carry out

their functions efficiently and without

incident. The U.S. Fleet withdrew from the area

during the night 4/5th November.

During the day aircraft from the British carrier

force attacked three enemy E-boats heading for

Alexandria. Two were sunk and the third, though

damaged, was allowed to pick up survivors from

the other boats and was seen making its way to

harbour.

Two further problems were to arise before the

actual assault. By 4th November I had been

informed that I could no longer count on the

arrival of 10 Armoured Division from Libya. This

formation was therefore removed from the Order

of Battle. I was offered instead 3 Infantry

Brigade which had come out from England to

replace 10 Armoured Division in Libya and was

then in Malta. General Stockwell considered he

did not require any more infantry but might

later need additional armoured units. Two such

regiments were then earmarked to come from the

United Kingdom.

At 2015 hours GMT on 4th November I was asked to

state, in the event of a postponement of the

airborne assault for 24 hours being ordered for

political reasons, what was the latest time by

which a decision must be made. In reply I gave

the hour as 2300 hours GMT and added that any

such postponement would have most serious

consequences and must be avoided at all costs.

Admiral Barjot fully supported my views. It was

accordingly agreed there should be no

postponement and the stage was now set for the

assault.

SIX

The Airborne

Assault—5th November

The morning of 5th November broke clear, with a

light wind, and for some hours beforehand Allied

paratroopers had been loading and emplaning in

their aircraft on Nicosia and Tymbou airfields.

At 0820 hours GMT 3 Parachute Battalion Group

and 16 Parachute Brigade Tactical HQ, some 600

strong, began their jump on to Gamil Airfield to

the West of the town. A few minutes later 500

men from the 2 Regiment Parachutistes Coloniaux

(2RPC) dropped near the water works to the South

of Port Said.

Anti-aircraft fire was encountered and was dealt

with by anti-flak patrols of shore based

aircraft. Although nine transport aircraft were

hit there were no casualties and all returned

safely to their base.

Both landings were successful although they were

met with considerable fire from machine guns,

mortars and anti-aircraft guns used in a ground

role and from self-propelled guns, the Russian

self-propelled SU 100's. The French quickly

secured intact their two important objectives,

the water works and the main road and rail

bridge over the Interior Basin. The Egyptians

succeeded in destroying the less important

pontoon bridge. The Water works were of

particular value for, although we had made

provision to supply the town by water tanker, in

that event strict water rationing would have

been necessary.

By 0900 hours the airfield was securely in our

hands and shortly afterwards a helicopter was

able to land to take off casualties. 3 Parachute

Battalion then advanced eastwards towards Port

Said town.

A particular centre of resistance which for a

time held up the Eastward advance of the British

parachute force was the Coastguard Barracks,

which were demolished by an extremely accurate

air strike by Wyverns and Sea Hawks of the Fleet

Air Arm without damage to surrounding buildings.

Meanwhile the Russian self-propelled anti-tank

guns (SU 100's) which had been dug in along the

foreshore left their emplacements and turned to

meet the threat from Gamil.

These guns were most skilfully handled and

caused us considerable trouble, the fighting

here was hard and the Egyptians made good use of

their dug positions which were often difficult

to locate. I warned General Stockwell that

unless the parachute operation achieved complete

success these armoured self-propelled guns might

have to be neutralised by destroyer fire before

the seaborne landing was made next day.

Egyptian resistance was very stubborn throughout

the morning. It centred mainly round the SU

100's which were being used as mobile centres of

resistance. By degrees the 3 Parachute Battalion

overcame these positions and under continuous

fire made further progress towards the town.

One of the features of this operation was the

excellent support provided by the aircraft from

the Carrier Force. Continuous missions were

flown throughout the day and there was always a

"cab rank" of British and French aircraft

overhead waiting to be called down on targets by

the troops on the ground. Such targets as

presented themselves were for the most part on

the outskirts of the town. Shore based fighters

and ground attack aircraft meanwhile made

certain that no revival was possible from the

Egyptian Air Force and that no reinforcements

reached Port Said.

At 1345 hours GMT a second drop of 100 men of 3

Parachute Battalion Group with vehicles, heavy

equipment and re-supply was made at Gamil. Some

460 French parachutists of 2 Regiment

Parachutistes Coloniaux dropped on the Southern

outskirts of Port Fuad: here for a time

resistance was stubborn and some 60 of the enemy

were killed, thereafter opposition at Port Fuad

collapsed. Egyptian military vehicles made for

the ferry across the harbour and were attacked

with great effect from the air.

At 1500 hours GMT the local Egyptian Commander

in Port Fuad contacted the Commanding Officer of

2 Regiment Parachutistes Coloniaux to discuss

surrender terms on behalf of the Governor and

Military Commander of Port Said. The latter was

referred to Brigadier M. A. H. Butler, DSO.,

MC., Commander of 16 Parachute Brigade, who was

in control of the whole airborne assault and who

had dropped at Gamil. Half an hour later at 1530

hours GMT a Cease Fire was ordered by the

Commander in Port Said while negotiations were

in progress. Surrender terms were agreed and the

Egyptian forces began to lay down their arms

while their police were assisting under orders.

Subsequently, however, the proposed terms were

rejected by the Egyptians, and operations were

resumed at 2030 hours GMT. It was later

confirmed that the matter had been referred to

Cairo whence orders had been issued for the

fight to be continued. Although we had cut all

possible telephone communications, there were

wireless sets and an underwater cable which we

had not the resources to destroy in time. On the

resumption of operations, the Garrison and

populace were encouraged to resist by

loudspeaker vans which toured the town

announcing that Russian help was on the way,

that London and Paris had been bombed and that

the Third World War had started. At the same

time arms were distributed to civilians, some

from lorries and some from piles dumped in the

streets. These arms appear to have been handed

out to all civilians, many of whom used them

indiscriminately, causing casualties to both

sides.

Up to this stage there had been very little

fighting in built up areas and hence few

casualties had been caused to civilians or

damage to private property.

In Port Fuad 2 Regiment Parachutistes Coloniaux

met little further resistance and completed the

capture of the area during the hours of

darkness. 3 Parachute Battalion were however up

against much stiffer resistance. On the narrow

strip of land between the sea and Lake Mansala

they came under fire from mortars, including the

Russian multi-barrel type, from Arab Town.

It was now clear that Port Said could not be

captured and cleared by the Parachute Force

alone and that the seaborne force would have to

make an opposed landing the next morning.

The decision to launch a comparatively small

airborne force without preliminary air bombing

or naval bombardment against a large town, whose

defence was numerically nearly three times as

strong and was supported by armour, had proved a

justifiable risk. Port Fuad, the water works and

the most important bridge to the South had been

captured intact and a small but serviceable

airfield was in our hands. All this had been

achieved with few casualties to our own troops

and negligible casualties to civilians or damage

to property. The subsequent tribulations which

were suffered by Port Said were entirely due to

the local Commander being overruled and

instructed to continue the battle.

SEVEN

The Seaborne

Assault—6th November

The heavy air and naval pre-assault fire

plan had been drastically reduced and I had

issued precise instructions that supporting fire

was to be confined strictly to known enemy

defences and to those which engaged our assault.

Air bombing was prohibited and heavy naval guns

were banned.

We thus maintained our policy of accepting risks

to our own forces in order to minimise Egyptian

civilian casualties and damage to their

property. The results bear witness to the

effectiveness of these measures and their strict

observance by the forces engaged, despite the

distorted and exaggerated reports broadcast from

Cairo and circulated throughout the world.

For 45 minutes before the landing some 3000

yards of the beach were subjected to covering

fire from destroyers. The object of this fire,

which was extremely accurate, was to neutralise

known enemy positions which had been dug amongst

the bathing huts on the foreshore. That it

achieved its purpose was evident from the

quantity of ammunition and equipment which was

later found abandoned on the beaches. Although

this fire was comparatively light and was only

used against known positions or SP guns which

actively fired, it achieved the result of

enabling our forces to land without suffering

the casualties usually expected in an assault

against a defended and mined coast.

It was not found necessary to engage the coast

defence guns on the breakwater which were silent

and had evidently been neutralised after

previously being attacked from the air.

Fortunately also the French Parachute force had

completed the occupation of Port Fuad during the

night so that the French seaborne landing on

this flank required no supporting fire.

Further support for the assault on Port Said was

provided by an air strike on the beaches lasting

for 10 minutes immediately before the start of

the naval gunfire: the beaches were again

engaged in a low level attack along their whole

length after the naval fire had stopped and just

before the leading troops reached the shore.

Preceded by minesweepers the assault force

reached its destination exactly on time after

the sea passage from Malta of over 900 miles

having taken 6 days. At 0450 hours GMT the

leading waves of 40 and 42 Royal Marine

Commandos came ashore and across the beaches in

LVTs (Landing Vehicle Tracked) before

disembarking. This obviated what otherwise would

have been an excessively long wade on the

gradually shelving beach, and an exposed run

across the broad beaches before reaching cover.

One squadron of the 6th Royal Tank Regiment was

waterproofed and waded ashore from LCTs (Landing

Craft Tanks) which touched down in 4 1/2 feet of

water.

At the same time the French Assault Force

consisting of 1st Regiment Etranger

Parachutistes and three Naval Commandos,

supported by a squadron of light tanks, was

making an unopposed landing on the beaches of

Port Fuad.

As the Royal Marine Commandos passed through the

beach huts, which were by then on fire and

amongst which quantities of abandoned ammunition

were exploding, they came under small arms fire

from buildings along the sea front and one SU

100 on their right flank opened fire on one of

the supporting destroyers. The destroyer

returned the fire and as a result conflagration

started in the shanty town in the immediate

neighbourhood of the SU 100; fanned by a stiff

breeze a large area of this collection of shacks

was burnt out.

Luckily an area free of the Russian mines placed

along the beaches was found at the point of

assault.

The objectives of 42 Commando supported by the

tank squadron less one troop, was to get through

Port Said as quickly as possible to the area of

Golf Course Camp and thereby seal off the

Southern exits of the town, while 40 Commando

with one troop of tanks was to clear the

vicinity of the harbour in order to enable craft

to enter without coming under fire.

42 Commando met considerable resistance in the

area of the Governorate where 100 to 150

Egyptian Infantry debouched from buildings South

and West of the Square. They were engaged by

supporting tanks, but as they continued to hold

out in a block of buildings which lay across the

main axis of advance of 42 Commando, an air

strike was called down at 0700 hours GMT.

Immediately after this the advance was resumed

with the Commandos travelling in their

unarmoured open LVTs escorted by tanks. They

moved rapidly down the Rue Mahomet Ali coming

under fire from side streets with grenades being

thrown down from balconies overhead.

The Commandos replied with their personal

weapons - while the tanks knocked out anti-tank

guns halfway down the street and overran a

further three guns as they emerged into the open

South of the heavily built up area.

The Commandos suffered some casualties at this

stage in their vehicles and while subsequently

clearing the houses on either side of the

street.

Meanwhile 40 Commando was carrying out a

deliberate clearance of the houses along the

Quai Sultan Hussein bordering the harbour. A

considerable number of Egyptian infantry were

seen and engaged to the West of this axis and

strong opposition developed amongst the

warehouses behind Navy House.

At 0540 hours GMT the Commanding Officer of 45

Commando took off from HMS Ocean in a helicopter

to reconnoitre the landing zone for his unit. In

the smoke and haze the pilot lost his way and

landed temporarily in an Egyptian held football

stadium where the party came under fire. Quickly

realising his mistake he re-embarked his

passengers and made good his escape in spite of

a considerable number of bullet holes in his

machine.

45 Commando were landed using 22 helicopters

from HMS Ocean and Theseus and 90 minutes later

400 men and 23 tons of stores were ashore near

the Casino Pier without further incident. This

was the first occasion on which such an

operation had been carried out.

The remainder of 6 Royal Tank Regiment

disembarked at the Fishing Harbour later in the

morning. One squadron was placed in support of

45 Commando who had the task of clearing the

town between the axes of the two leading

Commandos: the other squadron by-passed the

opposition with which 40 Commando was dealing

and finally joined up with the French

parachutists well South of the town near the

bridges over the Interior Basin.

By 0730 hours GMT 42 Commando and its supporting

tanks had taken up positions in the area of the

Gas Works and Golf Course Camp South of the town

from which they engaged Egyptian infantry near

the Prison. These appeared to be forming up for

a counterattack and an air strike was called

down on them at 0900 hours whereupon they

rapidly dispersed.

From then onwards until 1200 hours GMT 42

Commando engaged Egyptian infantry trying to

cross their axis from East to West evidently

seeking sanctuary in the rabbit warren of Arab

Town. This Westward move was also due to

pressure from 45 Commando who were slowly

clearing the middle of Port Said.

Like all street fighting the clearing of Port

Said was a slow process made more difficult by

the fact that most of the regular Egyptian

troops had by then discarded their uniforms for

"gallabiyahs", and were indistinguishable from

civilians, many of whom were armed.

Streets had to be cleared house by house and

sometimes room by room. This took time and

required a considerable expenditure of small

arms ammunition and grenades. Failure to observe

the normal street fighting drill and the wish of

all ranks to get through Port Said as quickly as

possible led in some cases to avoidable

casualties to our own troops. It is a tribute to

their patience and forbearanoe that so little

damage was done to Port Said.

At 0900 hours GMT Lieutenant-General Stockwell

reported that, with the other Task Force

Commanders and General Beaufre, he was going

ashore to try to secure the unconditional

surrender otf Port Said. Negotiations were in

(progress through the Italian Consul and a

rendezvous had been arranged at the Consulate.

Lieutenant-General Stockwell and his party

sailed into the harbour in a motor launch as far

as the Canal Company building where they were

fired on from the direction of Navy House. Going

about they landed near the Casino Palace Hotel

and proceeded to the Consulate. The Egyptian

Commander however failed to come to the

rendezvous and as a result fighting continued

throughout the day.

By 1015 hours GMT a tough battle was taking

place in Port Said but the situation was

gradually being brought under control. British

and French forces had linked up at the Water

Works and the advance Southward was being

organised.

I was particularly anxious to secure as much of

the Causeway running South from Port Said as

quickly as possible, mainly in order to prevent

our break-out from the Causeway from being

blocked by the Egyptians but also to enable Port

Said to be used for unloading men and material

without interference or the requirement of a lot

of troops to secure it.

In Port Said the last area of resistance centred

round Navy House where tanks supporting 40

Commando used their guns to blow in the doors of

warehouses from which Egyptian fire was still

coming.

Finally, just before dusk an air attack was

called down on Navy House itself which still

held out. This building was engaged and our

troops occupied the area. All organised

resistance now ceased, 3 Parachute Battalion had

also closed up to the edge of Arab Town and the

Commandos bad linked up with the French South of

the town. Sporadic sniping however continued

throughout the night.

At 1700 hours GMT orders were received

from London that a United Nations Force would

take over from us and that a Cease Fire was to

take effect 2359 hours GMT, and that no further

move of forces would take place after that hour.

Orders were therefore issued to the leading

troops to halt at midnight by which time the

leading Allied Forces had reached El Cap, some

23 miles South of Port Said.

EIGHT

The Occupation

of Port Said

Early the next morning I flew into Gamil

airfield and joined General Stockwell there. We

then toured the town together in a Land Rover

which enabled me to get a first hand impression

of the situation in Port Said and the fighting.

The Egyptian Garrison had consisted of three

regular battalions supported by Russian

self-propelled anti-tank guns (SU 100's) and a

considerable number of anti-aircraft guns which

had been used in a ground role after the

parachute drop. The Garrison had been swollen by

a last minute influx from Sinai and there were

some 4,500 Egyptian regular troops in the area.

Arms and ammunition, mainly of Soviet

manufacture, had been supplied on a lavish scale

and there had been a widespread distribution to

civilians of all ages. The scale of this can be

judged from the fact that on 8th November 45

Commando recovered fifty-seven 3-ton truck loads

off arms and ammunition from the area round Arab

Town. This material was mainly surrendered by

Egyptians in civilian clothes.

British casualties had amounted to 16 killed and

96 wounded, while the French had had 10 killed

and 33 wounded. The value of helicopters for

evacuating fthe wounded to the aircraft carriers

was amply demonstrated. The French had convened

a large liner as a hospital ship.

The Egyptian casualties were much more difficult

to assess at the time since the civilian

administration had broken down and no records of

dead or wounded were available. Neither was it

possible to distinguish between military

casualties who had abandoned their uniforms, and

civilians, who were killed or wounded with arms

in their hands.

The damage to property was mainly confined to

buildings along the sea front, the burnt out

portion of shanty town, the block near the

Governorate and Navy Housb, both of which had

been attacked from the air with rockets. Damage

to the main town was remarkably slight.

The subject of Egyptian casualties and damage to

property has since been thoroughly investigated,

first by Sir Walter Monckton and then by Sir

Edwin Herbert, whose findings have been

published in a Government White Paper.

The situation in Port Said on November 8th was

then as follows:

Tactical Headquarters of the Joint Task Force

was in HMS Tyne moored alongside the Western

breakwater. 3 Commando Brigade together with 6

Royal Tank Regiment and 3 Field Squadron RE were

engaged in clearing up the Northern part of the

town. Port Fuad was occupied by the French. One

battalion of 16 Parachute Brigade was on Gamil

Airfield, the French Parachute battalion round

the water works, and a British Parachute

battalion with a French element was at El Cap.

During the day a clash took place here, either

because the local Egyptian troops were unaware

of the Cease Fire or as an act of deliberate

provocation.

From now onwards great efforts were made to

restore the administation of Port Said to

normal. The Egyptian administration was

bolstered up by our Civil Affairs Officers, food

distribution was organised, public utilities

such as sewage and electric light were quickly

repaired and the streets cleaned up. Fortunately

the water works were intact, but a careful watch

was kept on the level of the Sweetwater (or

Ismailia) Canal in case the Egyptian

Army chose to restrict the flow of water to Port

Said. Arrangements were also made to accept a

hospital train from Cairo whose despatch was

organised through United Nations channels.

High priority was given to salvage operations

and teams immediately started to inspect the

wrecks sunk by the Egyptians. There were 21 of

these in the harbour, far more than air

photographs had disclosed since many of them

were completely submerged. Blocking of the

harbour had been catered for in the planning and

two salvage ships, an ocean tug and four harbour

tugs together with the necessary Clearance

Diving Teams and HMS Dalrymple (wreck dispersal

and survey vessel) had been included in the

assault convoy. The two salvage vessels entered

harbour on 7th November and by the 9th November

a channel had been marked through the

blockships. Further salvage vessels continued to

arrive over the next week, but it was not until

12th November that the first LST was able to

pass through the blockships and berth in the

inner harbour. Search for obstructions was

extended down to El Cap while considerable

progress was made in actual salvage work and a

base was established on shore by the time the

main salvage force arrived.

On 9th November I was instructed that the policy

of Her Majesty's Government and the French

Government was to retain our hold in Port Said

until the United Nations Force was established

there and that we should do so in sufficient

strength to insure against a breach of the Cease

Fire.

The Allied Forces were to be redeployed as

follows:—

Naval Forces

Two British and

one French Carrier to remain on station in the

Eastern Mediterranean.

Ships for picket duties were to take station

off Cyprus.

Cyprus

A minesweeping

force, salvage and clearance ships would

remain until the Canal and its approaches were

clear, a Red Sea element being based on Aden.

Land Forces

In Port Said the

build-up of 3 Infantry Division, less 1 Guards

Brigade, was to be continued until completed.

The French were to provide the equivalent of

the one Brigade Group in Port Fuad.

16 Parachute Brigade to be withdrawn to the

United Kingdom, less one battalion group in

Cyprus.

3 Commando Brigade was to return to Malta.

3 Infantry Brigade from Malta and 1 Guards

Brigade from the United Kingdom to reinforce

Cyprus.

Air Forces

Of the bomber

force previously available 20 Valiants and 24

Canberras were to be held in the United

Kingdom at varying degrees of readiness. All

shore based aircraft in the Mediterranean were

to remain in position.

During the next few days the above plan was

modified to the extent of retaining the