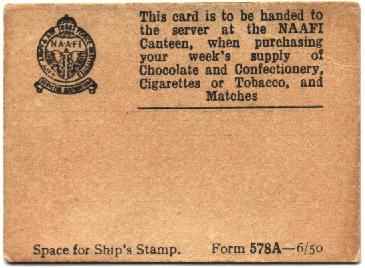

NAAFI Card - the Navy, Army and Air

Force Institution - part of the welcome we

shortly received in England

Late that afternoon appeared a

horse-drawn flat-topped cart on which was what I can only

describe as a bath, under which a fire was blazing. The

whole get-up was convoyed by Russians. Some on the cart

were evidently the cooks, stirring whatever was cooking

in the bath, with some scooping up chickens and

dispatching them, to throw them to the riders for onward

treatment. What a stew that must have made! They even

tried to round up one of the cows, but the Americans

stopped that and gave them cigarettes in lieu. I wonder

if they had the ‘trots’ next morning after that

meal, the way I suffered after the hot pork. They were on

the road to freedom, with a long way to go, so perhaps

they didn’t care. What must the villagers have

thought when they heard that Russians were passing

through? Those lads must have lived well on their

journey. I like to think that they might have passed

through Freiburg and dispatched some of those geese into

the bath! Pick ‘em up and put ‘em down.

Seeing the cow being chased gave me an

idea and I walked to one of the cow sheds, with the idea

of obtaining milk. Busily cleaning out the cowshed was a

young woman who was a conscripted worker from the

Ukraine. When I asked for some milk, she told me I must

return early in the morning at milking time and invited

me to visit the building which was the living quarters

for her and her compatriots. The inside was very much

like the inside of our huts: three-tier bunks, but this

time boys and girls lived together. They wanted to know

what had been happening and were amazed to learn that

they, like us, were free. When the conversation turned to

milk and why I required some, I mentioned that it was to

use with coffee. At that their ears literally pricked up.

Telling them to wait, I went back to the American

sergeant who gave me some packets of coffee, which I took

to them. They were profuse in their thanks, telling me to

be at the cowshed at six in the morning.

I don’t suppose many of us slept

very long that night. Excitement was still in the air and

I was up and about long before six o’ clock - or so

my watches told me. On entering the cowshed I saw the

young lady sitting on a one-legged stool, milking a cow.

She told me to take a similar stool, showed me where to

sit and told me to begin milking. I had never milked a

cow in my life and, when going through the motions of

pulling a cow’s teats, produced nothing. Even the

poor old animal mooed and looked back at me to see who

was operating at its other end. I might just as well have

used its tail as a pump for all the good I was doing.

Eventually the milk-maid came to my assistance to show me

the correct way and, much to my surprise, the cow

condescended to release some milk. Not a lot, but the

sound of the milk falling to the bottom of that bucket

made me think of a picture of a milkmaid jetting milk

from a cow’s teat at a cat sitting expectantly

nearby. After a while my wrists had had enough, but I had

obtained about half a bucket of milk. The milkmaid asked

if I had finished and laughed when she saw the amount I

had obtained. Saying: "Komm", she took the

bucket to a calf which, with one slurp, emptied the

bucket. Looking at my amazed face, the girl gave a lovely

laugh, which was something I hadn’t heard for a very

long time. Then she went back to the cow on which I had

been operating and the milk began to flow into the bucket

with a musical rhythm. We went back to their dwelling,

where she gave me a large metal container of milk. I gave

them my tin of nine cigarettes and a bar of American

chocolate to the girl who, as she was saying her thanks,

began to cry. What a contrast it was to the pleasant

laughter of a few minutes before - again something I

hadn’t heard in a long time.

There had been an issue of a breakfast

pack of American "K" rations, containing dried

egg powder, which to me was a revelation, a packet of

coffee, some biscuits, cigarettes and even toilet paper,

amongst other goodies which I have forgotten. By now four

of us naval lads had teamed up, the French frying pan was

brought into use, coffee made with milk and so our first

Freedom breakfast was fried egg powder and biscuits

washed down with hot coffee made with fresh milk. We had

plenty of firewood by breaking some of the wooden fences.

Soon after ‘chow time’, as the Americans called

meal-time, army trucks began to arrive to transport us to

a captured airfield, which was serving as a reception

area for us. And so I left my last place of captivity,

not picking ‘em up and putting ‘em down, but in

the comparative luxury of an American Army truck. We rode

for a couple of hours, winding round country lanes. We

had been released about forty miles from that airfield

and when we arrived we were told to find a billet in one

of the empty huts which had previously housed enemy

airmen; the interiors weren’t much of an improvement

upon our previous living arrangements. Better lighting

and better lockers, but three-tier bunk beds, together

with similar tables and stools.

By the time I arrived at that airport

those once-new boots I had put on early in January had

been just about walked off my feet. The end of the

"Wheatsheaf" brand boots had arrived. I

searched for the American sergeant, who by now was

calling me ‘Limey’ - the name any British

sailor is known by to the cousins on the other side of

the ‘pond’, because in the Tropics a daily

issue of lime-juice is given to all personnel of the

Royal Navy. Showing him my footwear I enquired about the

possibility of obtaining a pair of boots. He directed me

to a hut, the inside of which was lined with American

Army service boots. A soldier was stacking them to create

space. When I told him that the sergeant had sent me to

find a pair, I was told to help myself and he let me know

that the boots had been collected from men who had been

killed in action. I sorted through the unstacked heap

until I found two boots which fitted - a pair of high

lace-up boots with sturdy support for the ankles. My poor

old pair of worn out black boots I secured to one another

by the laces and carefully placed them on the top of one

of the prepared stacks. That pair had served me well and

deserved a good rest. Vive la "Wheatsheaf"!

That is the best recommendation I can give to that brand.

On my way out of the hut the soldier

asked me if I wanted a ‘K’ ration and, without

my replying, told me to follow him into the adjoining

hut, where cartons of packets were stored. Having had a

breakfast pack, I asked for a lunch pack, whereupon we

went to a stack of cartons and I began to open one and

remove a pack. He knocked my hand away and told me to

take the whole carton. I stood amazed for a moment; this

was a repetition of Mad Sunday. He told me to share the

carton with my buddies: "There’s no shortage

here; you’ll be fed up with them before long."

I thought to myself that he should have been living with

us for the last four months.

Expressions fail me when it comes to

trying to describe the generosity of the American

Services whilst I was at that airfield. In no time at

all, long trestle tables were set up - and I do mean

‘long’. Each table groaned with anything and

everything I had dreamed about whilst in that state of

deprivation. They were piled high with bars of chocolate,

cartons of cigarettes, soap, all kinds of toiletries,

books, newspapers, comic papers, ‘K’ rations -

in fact, you name it and it was to be found somewhere on

those trestle tables. To cap it all, there were American

uniformed ladies behind the tables saying: "Help

yourself, honey. There’s plenty more for you

boys." They were just heaping things on us. It just

wasn’t happening - but it was! After those years of

famine, one would have expected a mad rush, but no; there

was such a huge assortment available that you could

compare it with walking around a supermarket with a

shopping trolley today, with those girls urging us:

"Help yourselves, honey." Each day, more

released P.O.W’s were arriving and the amounts on

the trestle tables were constantly replenished. We lived

on ‘K’ rations which were heavenly. And the

weather was fine, as if trying to make up for the harsh

winter.

One day the American sergeant caught up

with me and took me off in a Jeep. At the far end of the

airfield was a stone-built hut with padlocked corrugated

doors. He used his machine gun to shoot off the padlock

and inside we found we were in a parachute store. Besides

wanting a gold watch, the sergeant now wanted a cuckoo

clock, so he decided to fill the back of the Jeep with

parachutes. We drove around the villages, where he

attempted to exchange a parachute for a cuckoo clock or

even a gold watch, but none were in evidence. He did

collect a good number of eggs and some smoked hams,

though. The only name I could think of for a cuckoo clock

was a ‘bird clock’, calling it a

‘Vogel-Uhr’ and making cuckoo noises, but it

didn’t seem to register and the villagers looked at

me with sympathy, as if I was ‘bomb-happy’.

When I asked the sergeant why he didn’t bring one of

his German-speaking buddies, he replied that what they

didn’t know wouldn’t hurt them. I often compare

him to Sergeant Bilko. When I recall that the right name

for that type of clock is ‘Kuckucksuhr’ and

that ‘Kuckuck’ is another word for

‘Dummkopf’, I realise it was no wonder that the

villagers looked at me as if I had a screw loose!

Very soon the airfield began to burst

at the seams with released personnel, but those trestle

tables continues to be piled high. Those good ladies

implored everybody to: "Help yourself, honey"

and then: "Don’t forget to take some home for

your folks!" As there was so much on offer I filled

my German rucksack with cartons of cigarettes,

‘K’ rations and bars of chocolate.

Then came the news I had been waiting

for. Next day all of us Brits would be transferred to a

British airfield for transport to the U.K. Next morning

we assembled outside our huts and several covered Army

trucks arrived. To my amazement we were to be escorted by

armed American soldiers in Jeeps and, more amazing, the

same sergeant was with us. Because we were to ride a

distance of about a hundred miles, we were each given a

small packet of biscuits and told to take a piece of

butter from one of the largest blocks I had seen in many

a year. Stuck in the top of the butter was a sort of

pallet knife and each person moved along the line to cut

out a knob before climbing into the lorry. When my turn

came to take some, something came over me and I sort of

lost all sense of self control. Taking the pallet knife,

I literally two-handedly attacked the butter and

succeeded in carving out a lump the size of a house brick

- all to put on a small packet of biscuits. At this

ridiculous action the soldier who was supervising the

distribution didn’t remonstrate or bat an eyelid. He

just calmly said: "What are you going to do with all

that?" Then I did feel like a Dummkopf and, when

sanity returned, I remember apologising, putting that

huge piece of butter back and taking a piece about the

size of a walnut. I wonder what a "trick

cyclist" would have made of that. Plenty

compensating for deprivation, perhaps.

In each lorry was a clean, new

galvanized bucket and, according to the sergeant, we

would stop at about lunchtime to find a house to supply

boiling water for coffee. Somewhere around lunchtime the

lorry stopped and the sergeant called for me to alight

with another fellow to walk up the drive of a house,

hidden behind some trees. The other lad was a Welsh

soldier. We carried the empty bucket; the sergeant had

several packets of coffee ready for the brew. He was also

carrying his machine gun, with which he banged on the

rather imposing door of the resplendant house and soon

the door was opened by a servant girl. I told her that we

wished for hot water to make coffee and she closed the

door, leaving us outside. We didn’t have to wait

very long before the door opened again and she invited us

into the kitchen. Here was a fairly young servant girl

who opened her eyes wide when I mentioned American

coffee, and even more when she saw the number of packets

of coffee which had been taken from the ‘K’

rations. A number of the packets were emptied into the

bucket, but I did manage to hang on to one to give to the

girl, who actually curtsied as she thanked me. With the

bucket nearly full with pungent smelling coffee we made

our way out to the entrance, to be met by an obese,

affluent German, who was evidently the owner of the

house. I described him as affluent because the waistcoat

adorning his ample stomach sported a gold watch chain.

How slow the American sergeant and I were. As we were

leaving the house, Taffy, the Welsh soldier, said to me:

"Sailor, ask him the time." Without thinking, I

said: "Wieviel Uhr ist es, bitte?" Whereupon

the affluent German gentleman lifted the gold chain to

take a GOLD WATCH from his waistcoat pocket. As quick as

a flash, the Welsh boy took the watch from the

German’s hand, unclipped it from the chain and said:

"This makes up for the watch I had taken when I was

captured." The American and I could only stand and

stare in astonishment. And neither of us in our amazement

thought to take the gold chain! The portly gentleman

began shouting: "Mein Uhr! Mein Uhr!" but we

took no notice and, with the bucket of coffee, walked

back to the lorry for a lunch of coffee, biscuits and

butter, shared with the soldiers in the guard jeep. Did

the American soldier ever find a gold watch? I wonder.