INTRODUCTION

NEVER in the history of the world

has sea power played so vital a part in the winning

of a war; and never, in proportion to the magnitude

of the forces and operations involved, has the Navy

played a part in which its proverbial silence has

been as marked as in the activities which terminated

on November 11, 1918, with the armistice between the

Allied and the Central Powers.

The war in its naval aspects, has

been a war of negative action; a series of

checkmates, by which the Allied navies secured the

seas from the interference of the grand fleets and

raiding squadrons of the enemy. But in this war the

submarine, a new weapon of offensive warfare,

imposed new conditions. Relatively secure in its

operations from the larger vessels of the Allied

navies, which themselves were in many instances its

ready prey, the submarine directed its activities

against the troop and store ships by which alone the

men and means to prosecute the war were made

possible.

To meet the preying warfare of the

submarine, the smaller and faster vessels of our

Navy were required in European waters, to assure the

safe and uninterrupted passage of our “bridge of

ships." It is not the purpose of this narrative to

deal with the operations of the United States Naval

Forces in English waters or in the Mediterranean. In

the north, the concerted action with the British

Navy, and in the south the cooperation with the

navies of France and Italy developed operations of

which it is impossible at this early date to secure

even casual data.

Of the activities of the United

States Naval Forces in France, it is possible,

however, to obtain more definite information, due

primarily to the fact that these operations were

more sharply defined and more distinctly our own. To

keep open the western coast of France was a task of

the most vital importance, involving a large and

capable organization and the utmost secrecy of

operation.

Due to this necessity for secrecy,

little has been known of the work of our Navy on the

French coast. To the majority of the American people

our men and stores have been transported with a

miraculous freedom from disaster, but the means by

which this security has been attained have been

unknown.

In no sense is this volume offered

as a history of the United States Naval Forces in

France, for a historic record of those splendid

activities would require a study of the complete

operations which is at the present time impossible.

Rather, it is the present purpose to afford, by a

few side lights on these activities of sixteen

months, a general view of the field and an

impression of the nature of the work involved. By

these, our most recent operations in the world's

most historic waters, the forces of the Navy not

only secured the desired safe passage of our troop

and store ships but by their cooperation with the

French Naval Forces and their association with the

people of the French nation, on land as on the sea,

established a sentiment of mutual affection and

esteem more permanent than can be obtained by

treaties or the written word.

More than the United States can

ever realize, does it owe to those who directed our

naval operations in French waters, a gratitude for

past performance and for future promise.

Brest,

France, December 2, 1918.

PREFACE

By

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Assistant

Secretary

of the Navy

THE Navy was known during the war

as the "Silent Service." Little appeared in official

dispatches or in the public press regarding the

operations of the United States Naval Forces either

in Europe or on our own coast. In fact, in only a

handful of instances, where a transport was

torpedoed or where an enemy submarine was definitely

accounted for, was any mention made of our naval

work. Generally speaking, the people at home knew

only that their Navy was successfully manning the

transports and escorting the troops, munitions, and

supplies in safety to the shores of France.

How very much more these operations

involved is only now coming out. On our entrance

into the Great War in the spring of 1917, steps were

immediately taken by the Navy Department to build up

an organization to be based on the French coast,

primarily for the purpose of keeping the famous

"Neck of the Bottle" as free as possible from German

submarines. The distance from Bordeaux to Brest is a

comparatively small one, and almost every ship

entering the French ports from the United States

had, of necessity, to pass through a narrow strip of

sea. This small area had proved a famous hunting

ground for enemy submarines, and it became our

obvious task to send over every possible means of

assistance to work with the French Navy.

The story of what our officers and

men did in those early days is the best illustration

of the all-round efficiency of the Navy. A large

proportion of the officers and men came from civil

life, but were quickly and successfully

indoctrinated into their naval duties by the regular

officers of the service. The tools with which they

had to work were, in large part, makeshift. Yachts

were hurriedly converted to naval purposes; all

kinds of equipment was taken over for possible use

in France. From small beginnings the organization

grew until by the summer of 1918 the whole western

coast of France was guarded by a string of surface

vessels and aircraft.

Not only was the ''Neck of the

Bottle" made safe for our troop and supply ships,

but the operations were extended from the defensive

type to the offensive, and the very existence of

enemy submarines was rendered extremely unhealthy

long before the armistice came.

To the men who took part in this

great work too much credit cannot be given.

Extraordinary physical endurance was called for, and

more than that, imagination and a genius to meet new

conditions with untried weapons was essential to

success.

During the summer of 1918 I had the

pleasure of visiting these French bases and of

seeing the work at first hand. No part of our naval

activities deserves higher credit than the part they

took. They have the satisfaction, at least, of

knowing that the Navy and the country are proud of

them.

Washington,

D. C, April 25, 1919

CHAPTER

I

FIRST

MONTHS OF THE WAR

WITH the entry of the United States

into the war with Germany and the Central Powers,

arose the immediate necessity of naval participation

and cooperation with the fleets of the Allied

nations. Never in the world's history had been

furnished an example so complete and so convincing

of the vital necessity of adequate sea power to

secure the desired victory over the common foe. For

three years the great fleets of England had been

holding in leash the German Navy, but despite the

assurance which England's fleet had given for the

protection of the seas from the German High Sea

Fleet, other grave dangers were clearly existent. In

the Channel, on the west coast of Ireland, along the

French coast and in the Mediterranean, the German

and Austrian submarines were waging a successful

warfare against the Allied shipping. To hold in port

the powerful Navy of Germany, the Grand Fleet of

England was chained to its guardianship of the

Helgoland gates, and on a similar duty the French

fleet watched the harbors and naval bases of Austria

in the Mediterranean.

The entry of the United States into

the war, created new problems which it alone must

solve; problems of transportation of troops and

supplies to the practically unprotected ports of

western France.

Tied hand and foot were the fleets

of the Allies. Not only did it devolve upon us to

deliver an army on French soil and the necessary

stores required by these hundreds of thousands of

fighting men; but it also became necessary for us in

large measure, to protect the passage and arrival of

the vessels required for troop and store transports.

From Calais the French coast slips

in a south-westerly direction, embracing in its

rugged coast line the ports of Boulogne, Le Havre

and Cherbourg, to the rocky point of Finisterre

where in a great sheltered harbor, at its western

extremity, rests the city of Brest, greatest of all

French seaports from the aspects of naval strategy.

From Brest, the coast runs southeasterly to the

Spanish line, including, from north to south, the

harbors of Lorient, Quiberon Bay, Saint-Nazaire, La

Rochelle, Rochefort, the Gironde River and Bordeaux,

the Adour River and Bayonne and the little southern

fishing port of Saint-Jean de Luz almost in the

shadow of the Pyrenees. Of these ports, Brest,

Lorient, Saint-Nazaire and the Gironde offered the

best facilities for the reception of troops and

stores; and it was here that the preliminary steps

were taken to prepare for their arrival. But the

great work of the Navy was apparently to be not on

French soil or on the wide Atlantic, but

particularly in the submarine danger zone which

naturally centered at those points on the French

coast where the greatest number of transatlantic

lanes converged; in other words, in the Bay of

Biscay at Brest, and in the Channel.

To understand more clearly the

nature of the convoy work, it may be divided into

two general classes:

First, the escorting into and out

of port through the danger zone of the

transatlantic convoys; and, second, the escorting

of the coastal convoys from port to port. The

mission of the United States Naval Forces in

France may thus be crystallized into the following

sentence: “To safeguard United States troop and

store ships and to cooperate with the French naval

authorities."

Granted, therefore, the hypothesis

that with a limited number of ports of arrival in

France the enemy submarines would have only to watch

the immediate approaches to these ports, the problem

became simplified and the work resolved itself into

a system of convoys, both coastal and deep sea, so

thorough in its character, that the submarines would

be forced from the entrances of the harbors and be

compelled to wait for the convoys at a considerable

distance off the coast and in the open sea where the

chance of meeting was materially reduced and where

the attendant dangers and hardships were greatly

increased.

On the entire western coast of

France and in the Channel, German submarines were

particularly active; it was but logical to calculate

that this activity would increase as the volume of

American shipping was augmented. To meet this

submarine blockade and carry against it a successful

warfare, was especially required a type of small and

swift vessels capable of mounting guns of

intermediate caliber and of being rapidly maneuvered

and, at the same time, possessing sufficient

seaworthy qualities to withstand the strains of

continuous service in waters notoriously

tempestuous. For this work the destroyer was

unquestionably the ideal type, but as the few

destroyers available had been sent to English

waters, the yachts were taken over and converted as

far as possible to meet the requirements. Later, by

the addition of a number of destroyers, it was

planned to provide a force of sufficient strength

and mobility to offset the submarine activities and

assure the safety required to place our troops and

stores on French soil. To cooperate with the United

States' Naval Forces, the French Navy afforded a

number of small destroyers and fast patrol boats,

suitably armed and familiar with the waters in which

the major operations would necessarily take place.

In addition, the French naval establishment

possessed adequate and most excellent mine-sweeping

facilities and also a limited force of hydroplanes

and dirigibles for cooperation with the patrol and

escort vessels.

It is appropriate to recall at the

beginning of this narrative of our latest naval

achievements that it was in these same historic

French waters, that our Navy found its birth, and

that in Quiberon Bay the Stars and Stripes, flying

from the U. S. S. Ranger of John Paul Jones,

received its first salute from a foreign nation when

the guns of the fleet of the French Admiral le

Motte, thundered a welcome to this new-born ensign

of the new-born nation across the sea.

On June 4, 1917, a small fleet of

six yachts left the New York Navy Yard and steamed

slowly down the stream. This force, a handful of

converted pleasure vessels, bore the official

designation of the U. S. Patrol Squadrons Operating

in European Waters and constituted the first

American naval participation in the Great War,

actually to be established in French waters. The

yachts were:

U. S. S. Kanawha

U. S. S. Vedette

U. S. S. Noma

U. S. S. Christabel

U. S. S. Harvard

U. S. S. Sultana

and also included in this force,

but temporarily under the orders of Rear-Admiral

Gleaves, were the U. S. S. Corsair and the U. S. S.

Aphrodite.

| |

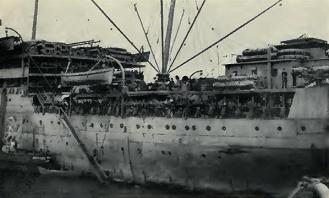

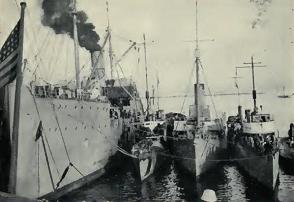

U. S. S. Noma

|

|

U. S. S. Christabel The smallest and oldest ship

in foreign service. The white star on the stack

means official credit for a submarine (Note:

this claim is not confirmed by post-war

research.)

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

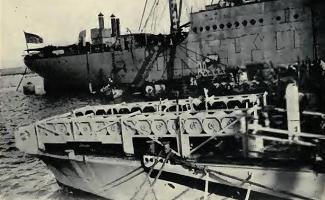

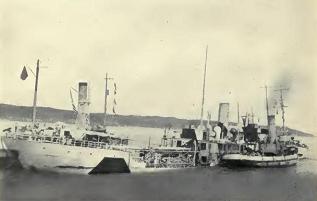

U. S. S. Rambler

|

|

U. S. S. Wanderer

|

|

For over a month work had been

pushed to the utmost to prepare the yachts for

foreign service. Furnishings and decorations of

peaceful days were removed and stored in Brooklyn

warehouses. White sides and glittering brightwork

were hidden under coats of battle gray. Fore and

aft, three-inch guns were mounted, and guns of

smaller caliber were located on the upper decks.

Cutlasses and rifles lined bulkheads of panelled oak

or mahogany. Everywhere about the ships improvised

quarters, in former smoking-rooms, libraries and

sun-parlors, housed crews expanded by war-time

necessity to four or five times the original quota

required to operate the yachts in time of peace.

The six yachts anchored until the

morning of June 9 off Tompkinsville, S. I., New

York, and at 5: 30 A.M. stood out to sea at a

standard speed of ten knots, en route to Bermuda. On

the twelfth of June, the force arrived at St.

George's Bay, coaled; on the sixteenth again got

under way and shaped a course for the Azores.

The yachts arrived at Brest,

France, on the fourth of July, after a relatively

uneventful voyage, where they found the Corsair and

the Aphrodite, which had arrived ahead of them due

to their greater size which enabled them to lay a

direct transatlantic course. On July 14, 1917, the

squadron commander, Captain W. B. Fletcher, U. S.

N., with his staff, secured quarters on shore and

began the first actual active cooperation with the

French Navy against the enemy submarines. It is of

historical interest to note that a few hours before

entering the harbor, the Noma sighted a periscope. A

few hours later, the S. S. Orleans was torpedoed,

probably by the same submarine which the Noma

sighted, and her thirty-seven survivors of the crew

and the thirteen members of the United States naval

armed guard were brought into Brest by the Sultana.

During

the month of July, the yachts received a strenuous

introduction to the patrol duty, which consisted of

a constant patrol of defined areas of water, so

continuous and so thorough that the submarine

activities, hitherto in a large measure undisputed,

were materially hampered and the safety of the

convoys passing through these waters was

proportionately increased. On the afternoon of the

twenty-ninth of August, the U. S. S. Guinevere and

the U. S. S. Carola IV, of the Second Squadron of

converted yachts, arrived at Brest, and on the

thirtieth, Commander F. N. Freeman, U. S. N., with

the yachts U. S. S. Alcedo, U. S. S. Wanderer, U. S.

S. Remlik, U. S. S. Corona, and U. S. S. Emeline

came into the harbor, delayed by storms and with

badly leaking decks.

Due to the unusually fantastic

scheme of camouflage which disguised the ships of

the Second Squadron, these yachts were commonly

known as the ''Easter Egg Fleet,” every conceivable

color having been incorporated in a riotous speckled

pattern on their sides. (Note: U.S.S. Corsair -

Lieut. Com. T. A. Kittinger, U.S.N., U.S.S.

Aphrodite - Lieut. Com. R. P. Craft, U.S.N,. U.S.S.

Noma - Lieut Com. L. R. Leahy, U.S.N., U.S.S.

Kanawha - Lieut. Com. H. D. Cooke, U.S.N., U.S.S.

Fedette - Lieut. Com. C. L. Hand, U.S.N., U.S.S.

Christabel - Lieutenant H. B. Riebe, U.S.N., U.S.S.

Harvard - Lieutenant A. G. Stirling, U.S.N,, U.S.S.

Sultana - Lieutenant E. G. Allen, U.S.N., Captain

William B. Fletcher, U.S.N., squadron commander.)

On the fifteenth of August, the

Noma reported the first actual engagement with any

enemy submarine as follows: ''At 2: 17 P.M. in

position Lat. 47° 40' N. Long. 5° 05' W. sighted a

suspicious object bearing about 245° (per standard

compass), distance about 6,000 yards. Object was

made out to be a submarine on the surface heading

about 320° psc. A discharge was being emitted by the

submarine, very much like smoke and was very

misleading. Submarine was evidently charging her

batteries. At 2:20 P.M. went to "general quarters"

and closed in on submarine. At 2:24 P.M. opened fire

with port battery, distance about 4,000 yards. Fired

ten shots. Submarine fired three shots at this ship,

one striking about 500 yards ahead of the ship and

the other two shots well over and on the quarter. At

2:27 P.M. the submarine submerged. Proceeded to

vicinity of submarine, but did not see her again. At

2:35 P.M. resumed our course."

Although the foregoing was the

first actual engagement, the Noma on August 8, in

response to an S. O. S. call, joined the S. S.

Dunraven, which was badly disabled by gunfire from a

submarine. This ship had been shelled from astern by

the submarine, one shell having exploded in the

after magazine and disabled the steering gear. Soon

after, the submarine approached closer to the

Dunraven and fired a torpedo. The submarine was in

this position when the Noma came up on the opposite

side of the torpedoed vessel. Two depth charges were

dropped by the Noma on the spot where the submarine

submerged, but these being of the early type, failed

to detonate.

The next squadron of the patrol

force, Captain T. P. Magruder, U. S. N., in command,

reached Brest on the afternoon of September 18, and

consisted of the yacht U. S. S. Wakiva, the supply

ship U. S. S. Bath, and the trawlers U. S. S.

Anderton, U. S. S. Lewes, U. S. S. Courtney, U. S.

S. McNeal, U. S. S. Cahill, U. S. S. James, U. S. S.

Rehoboth, U. S. S. Douglas, U. S. S. Hinton, and U.

S. S. Bauman. With these also arrived six 110-foot

patrol vessels, under the French flag. Due to the

construction of the trawlers, which was soon proved

to be entirely unsuited for the hard sea service

required, they were withdrawn after a few weeks from

escort duty and fitted for mine-sweeping.

It was during this period that the

United States armed transport Antilles in convoy

with a group of three transports and store ships and

escorted by the Corsair, Alcedo, and Kanawha, was

torpedoed and sunk, on the seventeenth of October,

outside of Quiberon Bay. No sign of a submarine was

seen. The total number of persons on board the

Antilles was 237, of whom 167 were rescued by the

escorting yachts.

During the month of October, 1917,

the coal-burning destroyers U. S. S. Smith, U. S. S.

Preston, U. S. S. Lamson, U. S. S. Flusser, and U.

S. S. Reid, arrived from Queenstown where they had

been receiving training. They were accompanied by

the U. S. S. Panther, a supply ship, which had

acquired historical interest as a transport in 1898

during the war with Spain. The addition of this

small destroyer flotilla was of inestimable value,

for the yachts, until this time, had been required

to perform the entire patrol and escort duty,

including the deep-sea troop convoys for which they

were structurally wholly unsuited and inadequate.

It is interesting to imagine the

hopes and fears of those early days of our

participation. In the ancient port of Brest but a

few remnants of the French fleet remained. The

streets of the gray town were deserted. Gone were

the seamen that for centuries had given it its

glory; gone too were the young men, now fighting and

dying on the northern lines of France. Small indeed

must have seemed these first contributions from the

great ally beyond the Atlantic. A few converted

yachts, a few destroyers; that was all. And yet,

within the brief span of a year this almost deserted

harbor was to become dense with shipping. Great

transports were to swing at moorings beyond the

breakwater. Wasp-like destroyers were to ride at

their buoys in the inner harbor in rapidly

increasing numbers. Khaki-clad soldiers by the

hundred thousand were to look upon the gray town and

pass on to their duty in the north. And from

nothing, the establishment of the United States

Naval Forces in France was to expand, with

characteristic American enterprise, into a vast

coherent organization, embracing in its manifold

ramifications the complete machinery for the

successful accomplishment of the tremendous work in

hand.

| |

Brest - The old château and a bit of the inner

harbor

|

|

The landing at Brest

|

|

The first six months of our

activities on the French coast were in a large part

a period of experiment. The force was entirely

inadequate; the ships soon proved unsuited for the

work required and the officers and men of the

reserve force were new to the work. There has been

little glory credited to the work that was

performed, for it was at no time a kind of work with

which glory associates most freely. Here was

drudgery and danger; a silent service secretly to be

performed. It was work for which a destroyer

flotilla of the largest and fastest vessels would

have been none too good. But such vessels were not

available. The yachts were sent. As months passed by

came slowly the coal-burning destroyers. Later came

the great oil burners, and the yachts disappeared

into the obscurity of hazardous coastal convoys and

the deep-sea convoys of merchantmen in the rough

waters of Biscay.

On October 21, 1917, Captain

Fletcher was detached, and shortly after,

Rear-Admiral Henry B. Wilson arrived to take up the

command. To Captain Fletcher should be given the

credit for the inception and early organization of

our naval forces on the French coast, credit which

alone can offset the trials and disappointments of

those early days. With the arrival of Rear-Admiral

Wilson began the second and final period; a period

of constant organization and amplification.

Fortunately endowed in generous measure with those

executive qualities characteristic of an American

naval officer, Admiral Wilson was still further

happy in the possession of a diplomatic nature and

keen sympathy with the French people. With the

limited tools available, he planned and executed a

program which proved itself in its attainment of the

desired end. And, as the means for prosecuting his

purpose were increased, he developed his plans the

further to assure their more perfect accomplishment.

On November 27, 19 17, the

destroyers U. S. S. Roe and U. S. S. Monaghan

arrived at Brest from Saint-Nazaire. Utilized

previously for deep-sea escort duty from the United

States they had never before touched at a French

port, turning always in mid-Atlantic and returning

to the United States. On this occasion, however,

they had been assigned to escort the U. S. S. San

Diego, on which Secretary of War Baker made passage

to France, and arriving at Saint-Nazaire, found it

necessary to proceed north to Brest for coal. As

this duty was unforeseen, they were without coastal

charts and proceeded to explore their way through

the perilous mine and submarine zones with a large

ocean chart as their only guide. Ignorant of the

coast, they first explored the Bay of Douarnenez,

but finding no city there, they kept on up the

coast. Inasmuch as their ocean chart did not show

the channel of Raz de Sein, they did not find it,

and passed around it into the Iroise. A message was

sent to them to avoid the Iroise, but as that also

was not shown on their chart, they were forced to

ignore the warning. Happily, they finally reached

Brest without accident, where they were later

permanently joined to the destroyer force there. The

destroyer U. S. S. Warrington joined the Brest

forces at about the same time.

In the middle of December, the

torpedo boats U. S. S. Truxton and U. S. S. Whipple

reached Brest, and shortly after, arrived the U. S.

S. Wadsworth, the first thousand-ton destroyer to be

assigned to the French waters.

In the forepart of 1918, the

Stewart and Worden, two of our oldest torpedo boats,

made a hazardous but successful transatlantic

passage in the extreme weather of midwinter. On

February 18, 1918, the repair ship Prometheus, the

torpedo boat Macdonough and the converted yacht

Isabel moored in the harbor, and with the passing

months the fleet was further augmented by the

arrival of the destroyers Porter, Wainwrite, Jarvis,

O’Brien, Benham, Winslow, Drayton, Gushing, Tucker,

Burrows, Cummings, Ericsson, Fanning, and McDougal.

These were followed later by the first of the new

flush-deck destroyers: Little, Sigourney, and

Conner; and about a month before the signing of the

armistice these were followed by the Taylor,

Stringham, Bell, Murray, and Fairfax. A fourth

flotilla of yachts arrived during February, under

the command of Commander David F. Boyd, U. S. N.,

and included the U. S. S. Nokomis, U. S. S. Rambler,

and U. S. S. Utowana and the tug Gypsum Queen.

Another yacht, the U. S. S. May, was also added to

the force, having proceeded to Brest from Portugal,

where she had left a number of submarine chasers

which she had escorted across the Atlantic. In

addition to these vessels were also added during the

forepart of the year, the tugs Barnegat and Concord

and the repair ship Bridgeport. On the eleventh of

November, 1918, when hostilities were suspended by

the armistice, the United States Naval Forces in

France comprised a total of thirty-five destroyers,

five torpedo boats, eighteen yachts, eight tugs,

nine mine-sweepers, three repair ships and one

barracks ship, three tenders, and one salvage

vessel.

Much has appeared in magazines and

newspapers of the actual debarkation of American

troops on French soil. Of those landing in England,

or the ports of other countries, we are not here

concerned. It is the purpose of this narrative to

deal solely with the activities of the American

Naval Forces in France, and accordingly only with

those troop ships and store ships which sailed from

American ports directly to ports in France. The

first American troops reached Saint-Nazaire on June

26, 1917. Perhaps never in the world's history, has

the deeper and finer sentiment of a nation been so

thoroughly aroused as on that famous day when the

first few thousands of khaki-clad soldiers touched

foot on the soil of France. A nation by nature of

the deepest sentiment, the people of this seaport

town, realized in this slender vanguard the vivid

expression of a friendship begun in our own struggle

for national freedom and sustained for a century and

a half with almost unbroken continuity.

During the second half of 1917, a

constantly increasing flood of American soldiers

were transported in safety to the shores of France.

With the new year, a greater volume began to arrive

and in the month of January, 25,280 men were landed.

February showed a slight loss, with a total of

17,483, which was offset by the total of 53,043 in

March and 62,615 in April. In May, the full flood

began with a total of 119,110. In June, 104,249 were

landed, a number which increased in July to 133,993.

There was a sudden drop in August to 93,376, but the

September quota of 143,253, established a new

record, closely followed by a total of 107,547 in

October. The grand total for the ten months of 1918

was 859,949.

There is no more inspiring sight

than the arrival of a troop convoy and the

description of a single instance may illustrate, as

characteristic, any of the one hundred and two troop

convoys which arrived during these ten months of

1918. At dawn the convoy of eight troop ships which

had been proceeding in a double line of four ships

each, formed single column, with three destroyers on

either flank. The sea was calm and the sun rose in a

soft-blue, cloudless sky. On the eastern horizon a

white lighthouse lifted sharply from the thin line

of the coast. The great troop ships, famous liners

of other days, rose and fell heavily on the low

swells, their high sides stripped and blocked in a

strange dress of blue, gray, white and black

camouflage, their decks brown with a solid mass of

soldiers straining their eyes to catch a first

glimpse of France. High overhead, two great yellow

French dirigibles moved with smooth rapidity. From

four gray hydroplanes, soaring in wide circles, came

the distant reverberation of motors. On either hand

the destroyers, lean, lithe sea-whippets, shook

their dipping bows and rolled in the swells with a

quick jerking motion. Over the water came the sound

of music; an Army band was playing on board the

nearest transport. The convoy passed into the

channel. On the south, great brown rocks lifted from

the sea, and on either side of the entrance to the

harbor, the black cliffs of Finistere, like twin

Gibraltars, marked the approach. The convoy,

steaming slowly, moved up the channel. The broad

blue harbor of Brest unfolded, crowded with

shipping. In the outer harbor great steamers swung

at their moorings, and behind the breakwater the

water was gay with camouflaged vessels, clusters of

destroyers and the gray hulls of two great repair

ships. Beyond the harbor swung the circle of the

green hills of Finistere, and on the left the gray

and ancient city of Brest rose sharply from the

historic fortress at the water's edge. Quietly the

destroyers slipped into the inner harbor and the

transports anchored outside the breakwater. They

were "over;" delivered safely through the danger

zone by the United States Naval Forces in France.

| |

The Leviathan

|

|

Troop Ship at Brest

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

A French Dirigible

|

|

German Sea Mines

|

|

Such, in general, was the work of

the Navy in French waters during the sixteen months

of its activity. It was a labor unenlivened by those

inspiring engagements between ships of a class which

marked our naval activities in these waters a

century and a half before. Rather, it was a struggle

with a force secretive, elusive, and mysterious.

There were thrusts in the dark from an unseen enemy;

there were engagements fought and won between ships

invisible to each other. Never could there be a

moment of relaxation; never did an empty ocean, blue

under a summer sky or gleaming in the moonlight,

assure the absence of the enemy. Great vessels under

escort were torpedoed, vessels of coastwise convoys

and vessels of the deep-sea traffic were sunk, but

small was the percentage of loss compared with the

numbers of the mighty argosies that in safety sailed

the sea and of greatest significance stands the fact

that not one loaded transport was destroyed or the

life of a single passenger lost. Few were the

absolute confirmations of the destruction of

submarines, but later events have disclosed a

mortality that does compliment to Yankee

perseverance and the depth charge, that frightful

enemy of the submarine, which took lavish toll of

the sea-wolves of the underseas.

CHAPTER

II

BUILDING

THE

MACHINE

THE arrival of Rear Admiral Henry

B. Wilson at Brest on Thursday, November 1, 1917,

and the hoisting of his flag on the U. S. S.

Panther, marked the beginning of the second and

final period of our naval activities in French

waters. On the staff of the Admiral were Commander

John Halligan, Jr., U. S. N. Chief of Staff,

Lieutenant Mahlon S. Tisdale, U. S. N., and

Lieutenant J. G. F. Reynolds, U. S. N. R. F., who

had accompanied Admiral Wilson from Gibraltar.

Admiral Fletcher's staff was assimilated and this

small nucleus grew to some seventy officers before

the armistice was signed. It is impossible

adequately to chronicle the development of these

months of organization and accomplishment. From the

first establishment of Captain Fletcher, the

organization was consistently developed to meet new

requirements constantly arising, requirements

necessitating the occupation of quarters on shore

which finally extended to the complete equipment

which existed at the final suspension of

hostilities. Offices were acquired and new space was

constantly added. Quarters for men on shore duty

were provided. Offices for the pay department were

secured; a department that at the close of the war

was in itself a complete organization, handling a

volume of business undreamed of by any of our own

Navy Yards, with the probable exception of the

Brooklyn Navy Yard, in the former days of peace. To

maintain good order throughout the city, a naval

patrol was established. A great post office, which

in one day received fifteen thousand sacks of mail,

was created. Coal, oil, and water facilities for the

ships were planned and arranged for. Communication

systems were instituted. And in all these various

activities, a cooperation was maintained with the

French authorities, both maritime and civil,

unbroken in the consistent spirit of enthusiastic

friendliness.

The rapidly increasing importance

of the United States Naval Forces in France required

a coherent and yet flexible organization under

single leadership, and on the twelfth of January,

1918, after calling Admiral Wilson to London for

conference the first definite amplification of the

organization of the United States Naval Forces in

France was outlined by Vice-Admiral Sims, Commander

United States Naval Forces operating in Europe, to

Rear Admiral Wilson. Under this new organization,

Admiral Wilson received the title of

"Commander United States Naval Forces in France" and

took command of all United States naval vessels

operating in French waters. As a result of this

comprehensive command, the organization was

naturally divided into two parts: the naval forces

afloat, including all ships assigned to duty in the

Channel and the Atlantic coasts of France, and the

Port Organization and Administration, comprising the

three districts of Brest, Lorient, and Rochefort,

with an officer of captain's rank in command of each

of these districts.

Aviation, under the command of

Captain H. I. Cone, was also included under the

command of Rear-Admiral Wilson, but due to the many

problems in this new branch of naval activities, a

free hand was given to Captain Cone in the building

up and perfecting of the naval aviation service and

it may be considered practically a distinct

organization during the phase of construction and

until the stations began to operate against the

submarines.

Commander W. R. Sayles, U. S. N.

(naval attache in Paris) was placed in command of

the Intelligence Service, and Captain R. H. Jackson,

U. S. N., became an officer on Admiral Wilson's

staff, to act primarily as liaison officer between

the Admiral and the French authorities, although the

right naturally remained to Admiral Wilson to deal

directly with the French Ministry of Marine if he

should so desire. As an addition to the Intelligence

Service, a counter espionage service was organized

under the command of Commander Sayles, and in order

to clarify the work, the various activities were

separated into six principal fields:

Naval Forces Afloat; Port

Organization and Administration; Aviation;

Intelligence; Communication; Supplies and

Disbursements.

In regard to the control of

shipping, it was determined that all troop and cargo

transports and other vessels flying the American

flag should be escorted to their wharf, anchorage or

buoy by the Navy, and that thereafter, their

subsequent movements, until they should be ready to

leave port, should be controlled by the Army or

Navy, according to whom their cargo belonged, and

that, upon leaving port, they would again revert to

naval control.

In accordance with this outline,

Admiral Wilson designated the three districts as

follows:

Brest to include the territory

extending from Brehat to Penmarch, including

Ushant; Lorient, the territory from Penmarch to

Fromentine, including Belle-Ile, and Rochefort,

the territory extending from Fromentine to the

Spanish line and including the outlying islands.

The district commander in charge of

each of these districts received immediate control

of operations of all vessels placed under his

command and was further charged with the

responsibility of repairing and supplying of vessels

assigned to his district; the development and

maintenance of adequate naval port facilities; the

establishment and maintenance of all communication

with the Commander United States Naval Forces in

France, the prefet maritime, the naval port officer

of the district, and the other district commanders

and the supervision of American shipping and of

United States naval personnel on merchant ships.

Naval port officers at all of the

principal ports, were established, reporting

immediately to their respective district commanders.

The duties of these port officers were primarily to

facilitate the berthing, discharging, and sailing of

United States troop and store ships, a duty which

included all of the arduous details which constantly

present themselves whenever shipping in any quantity

is present. Among the many duties assigned to port

officers, the following were perhaps of major

importance:

To cooperate with the United States

Army and the French authorities in the despatch of

vessels; to keep the Commander United States Naval

Forces in France and the district commander promptly

informed of the arrival and the departure of all

United States vessels; to obtain from the commanding

officers or masters of these vessels upon their

arrival, all interesting information regarding the

incidents of their voyage and their particular

needs; to inspect the United States naval armed

guard and radio men on all United States vessels,

other than those regularly commissioned in the

United States Navy and report on their efficiency;

to assist in supplying these vessels with necessary

fuel and supplies; to pay the armed guard and

furnish them with clothing and small stores; to

investigate offences committed by United States

naval personnel on vessels other than those

regularly commissioned United States naval vessels;

to investigate and take action on all admiralty

cases involving United States Navy; to keep the

Commander United States Naval Forces in France

informed of the readiness of all vessels and of the

speed which they were capable to maintain through

the danger zone; to familiarize the masters of ships

with the precautions and the prescribed convoy

scheme to be followed within the danger zone; to

furnish each convoy and its escort commander, prior

to sailing, with the latest information regarding

submarine and mine activities and to keep the

commander in France constantly informed as to the

amount of Navy coal on hand, expended and received.

It has been ever a part of the

Navy's duty to stand ready to assume responsibility

for the fulfillment of whatever work might be

required to prosper the best interests of the

Nation, for which the Navy has been and must

continue to be its outward manifestation throughout

the world. To create an organization, such as

conditions in France required, sufficient not only

to meet temporary needs, but also future

requirements and at the same time to carry on an

active warfare with a powerful enemy, was a

commission of the most grave responsibility, for it

required not only the abilities of trained men of

business, endowed with native American energy and

promptness of decision, but there were also required

those traits which are presumed to attach solely to

trained diplomats. For in all this tremendous

operation and creation, it was necessary to maintain

the utmost harmony and cordiality with a people

speaking a different tongue and accustomed to those

more composed and conservative methods of

accomplishment generally characteristic of an older

nation.

| |

A sea plane makes a bad dive. Destroyers to the

rescue

|

|

The destroyer Monaghan

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The hammer-head bow of a destroyer

(possibly the bow of Jarvis after she had rammed

Benham)

|

|

Depth charges on the stern of a destroyer

|

|

Throughout the entire history of

our naval cooperation with the French nation, a

spirit of cordiality and cooperation was

consistently maintained. Nor were these relations

broken by a single incident to mar the perfect

accord. The following telegram was received by

Admiral Wilson on July 1, 1918, from the French Vice

Admiral Schwerer and seems particularly felicitous

in the exact expression of the spirit existing

between the two nations:

On

July 4, 1917, there arrived in our waters the

first eight ships of war sent to France by the

United States to fight with us against the enemy's

piracy. These vessels were the yachts Harvard,

Vedette, Kanawha, Sultana, Christabel, Noma,

Corsair and Aphrodite. Since that period these

vessels have constantly collaborated with us in

the protection of convoys and we have all been

witnesses of the ardor and the devotion brought by

their personnel to the difficult and sometimes

ungrateful tasks of the patrols.

This

squadron was the vanguard of a flotilla of ships,

each day more numerous and more powerful, which

arrived from the other shore of the ocean to take

part in the fight.

At

the moment when the anniversary of the arrival in

Brest of this vanguard approaches, I am sure that

I am the interpreter of all the officers, petty

officers, and enlisted men of the divisions of

Bretagne, in addressing to our American comrades

the expression of our fraternal esteem and of our

warm admiration of your great nation which has not

hesitated to throw itself into the most terrible

of wars for the defense of Right, of Liberty, and

of Civilization.

(Signed)

Vice Admiral Schwerer,

Commandant

Supérieur des Divisions de Bretagne. Brest, July

1, 1918.

On July 4, 1918, the following

telegram was received by the Commander United States

Naval Forces in France, from the Minister of Marine:

At

the moment when the magnificent battalions of the

American Army are marching in Paris past the

statues of our cities unjustly occupied by the

enemy, thus affiirming the high ideals of justice

which lead them to fight by the side of our

soldiers, I am particularly happy to address to

you my most cordial regards in recognition of the

perfect and devoted cooperation which our naval

forces in Brittany have not ceased to find with

the American naval forces placed under your high

direction and the systematic harmony of views and

sentiments which has not ceased to reign between

us.

Rear-Admiral Wilson replied:

To

the Minister of Marine:

It

is a great honor and satisfaction to receive the

cordial good wishes expressed in your message of

today. The American Navy is proud of its privilege

of working with the French Navy, a service for

which we have the highest admiration. Our personal

association with the flag officers of your Navy

has been an inspiration to me.

(Signed)

H. B. Wilson.

On September 21;, 19 18, Rear

Admiral Henry B. Wilson, U. S. N., Commander United

States Naval Forces in France was promoted to the

rank of vice-admiral, U. S. N., and his flag was

hoisted on the flagship Prometheus,

There are times when only

statistics can giye a definite conception, and a few

figures selected from the mass of data relating to

these impressive operations may indicate in some

measure the scope of the accomplishment. From

nothing, on July 1, 1917, the United States Naval

Forces in France had grown by October 1, 1918, to an

establishment of 22,111 officers and men; of these

1,422 were officers. Afloat, the personnel numbered

601 officers and 7,480 men. Of the shore forces, 160

officers and 2,187 men were distributed among the

three base organizations; 71 officers and 207 men

among the port offices, 578 officers and 9,789 men

among the 16 naval air stations; 24 officers and 488

men with the naval railway battery; 18 officers and

556 men with the high power radio detachment and 27

officers and 58 men on detached staff service.

During the first nine months of

1918 an approximate total of 752,402 troops was

convoyed safely through the danger zone and landed

at French ports. On one day alone sixteen ships

containing over forty thousand men were brought in

safety into a single port. Two hundred and sixty

convoys, comprising 1,499 vessels, were convoyed,

during the same period through the zone, proceeding

either to French ports or homeward bound. And this

was accomplished by a fleet, all told, which reached

eighty odd vessels only a few weeks before the

armistice was signed, and was manned by

approximately eight thousand officers and men.

During the closing months of the

war, the activities of the base at Brest assumed

proportions far in excess of the anticipation of any

of those who contributed to the early days of its

establishment. Repairs to escort vessels,

transports, merchant ships, and vessels wrecked by

storm or collision, or torn by torpedoes,

necessitated operations similar to those required by

the most modern Navy Yards in the United States.

Repair shops afloat and on shore were working in

shifts, in order that the vast volume of work might

be accomplished. The administrative force had been

constantly increased to keep pace with these

developments and a continuously growing number of

enlisted men had required additional barracks on

shore.

CHAPTER

III

IN THE

PATH OF THE SUBMARINE

In the many engagements between

Allied vessels and German submarines in French

waters the fortitude of the officers and crews of

the smaller merchantmen and particularly of the

French fishing vessels afforded many dramatic

instances. Due to the limited number of French and

American patrol vessels it was but natural that many

of the smaller vessels took a "long chance" and

endeavored to make their way unescorted along the

coast. Many of these vessels were attacked and a

large number were destroyed; but out of the total

number of engagements there are several which

particularly illustrate the temper of the French

seaman in the face of almost overwhelming odds.

At about eleven o'clock of the

morning of December 4, 1917, the St. Antoine de

Padoue, a three-masted sailing vessel left Britton

Ferry for Fecamp. She was making about three or four

knots in a S. S. E. direction when a shell fell

about two hundred meters off the starboard bow and a

violent explosion was heard astern. The pilot who

was standing on the poop deck with the captain saw

the submarine which was headed N. E. at a distance

of four thousand meters on the port quarter.

“General quarters " was immediately sounded; the

captain ordered a zigzag course to be followed in

order to confuse the aim of the submarine, and

opened fire with his own guns. After seventeen shots

had been fired by the St. Antoine, the submarine

submerged and disappeared. The engagement had lasted

fifteen minutes and no damage was done to the

sailing vessel. But fifteen minutes later the

submarine reappeared and resumed firing at a

slightly increased distance. The first shell fell

short on the starboard side. The captain promptly

responded with his stern gun and resumed his zigzag,

but within a few minutes the sighting piece of the

gun was shot away and damage to the breech put the

gun temporarily out of action. Undaunted, the

captain maneuvered to bring his forward gun into

action, but a shot from the submarine struck the

port side of the sailing ship, inflicting severe

damage. In spite of the heavy fire which continued,

the men stuck to their posts and continued what

seemed to be a hopeless struggle. At the darkest

moment, however, a British hydroplane made its

appearance and caused the submarine to submerge.

This was the third time that the St. Antoine had

escaped after having been attacked by German

submarines and the captain had already been cited as

a result of these engagements.

| |

Destroyers waiting for an incoming convoy

|

|

Troop ship escorted by a destroyer and two sea

planes

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Observation balloon on a destroyer

|

|

The

balloon

going up

|

|

On another occasion, the St.

Antoine de Padoue was engaged in fishing off Fecamp.

While the crew were attending to their nets, a small

boat with two leg-o-mutton sails appeared on the

horizon at a distance of two or three miles. In

waters frequented by fishing boats the appearance of

a craft of this nature would not normally attract

attention, but in this particular instance the

vessel sighted seemed to be pursuing a course

parallel to the course of the St. Antoine, at a rate

of speed in excess of that justified by the small

size of her sails. The suspicions of the captain

were promptly aroused and he sent his crew to battle

stations. Gradually the courses of the two ships

converged and the St, Antoine fired a shot, hoping

that the suspicious vessel would show a signal. No

signal, however, appeared and a few minutes later

the sails were hauled down and a conning tower was

clearly seen in silhouette against the horizon. For

some reason unknown, no attack was offered, probably

due to the apparent readiness which the captain of

the St. Antoine showed for battle; and shortly after

the submarine disappeared and the St. Antoine

proceeded on her course.

Another interesting attack was

reported as having occurred on the ninth of January,

1917, against the French steamer Barsac, bound from

Brest to Le Havre. The Barsac, entirely darkened,

was proceeding at a speed of about ten knots, when

at 6:35 P.M. a torpedo suddenly exploded against the

side, opposite No. 3 hatch, promptly filling the

engine-room with water. The ship filled rapidly by

the stern and sank in three minutes. No one on board

saw either the submarine or the torpedo.

With the utmost calmness the crew

manned the boats, the captain alone remaining aboard

the stricken vessel. When the ship went down the

captain was dragged after her by the suction, but

coming to the surface was rescued about twenty

minutes later by one of the ship's boats. The

surviving members of the crew were finally picked up

by a patrol boat, but eighteen men were lost

On December 21, at a little after

one o'clock in the morning the Portuguese steamer

Boa Vista in convoy with five other ships escorted

by two French patrol boats, the Albatros and the

Sauterelle, were proceeding north, enroute for

Quiberon. The sea was calm and the night clear and

brilliant although there was no moon. No sign of

submarine activities appeared on the still water.

Suddenly, the Boa Vista was struck by a torpedo on

the starboard side a little forward of the bridge.

For half an hour the ship sank slowly by the bow.

The patrol boats "stood by," rescuing the crew and

endeavoring to take in tow the lifeboats which she

had launched. Suddenly the conning tower of the

submarine appeared at a distance of five thousand

meters and fired a second torpedo at the Boa Vista

which sank rapidly and disappeared five minutes

later.

Early in January, the steam trawler

St. Mathieu left Brest on her way to the fishing

grounds about one hundred miles S. S. W. of Raz de

Sein. In the morning of the sixth, when

seventy-seven miles S. W. of Belle-Ile, the lookout

sighted a boat on the horizon and a few seconds

afterward a shell passed over the St. Mathieu. The

captain promptly hauled in his nets, sent his crew

to battle stations and heading for the enemy, opened

fire with his bow gun. A few minutes later, a shell

from the submarine shattered the upper part of the

bridge, wounding the man at the wheel and another

near the bow. Encouraging his crew, the captain of

the trawler continued his action until another shell

from the submarine mortally wounded three of the

guns' crew, but undaunted, the only survivor

continued to fire until the ammunition was

exhausted. The submarine was now relatively near the

trawler and her fire was extremely accurate. By this

time, out of a total crew of thirteen on board the

trawler, four were killed, four badly wounded, and

all of the remaining were suffering from minor

injuries.

It was now necessary to abandon

ship and the captain with the survivors put off in a

small boat. A few minutes later the submarine sank

the St. Mathieu by gunfire and promptly submerged.

Then followed thirty hours of great suffering on the

part of the crew of the trawler, all of whom were

more or less wounded. A heavy sea was running and

navigation was difficult. The night was very dark.

Toward morning a patrol vessel heard the cries of

the sailors, but in her attempt to effect a rescue,

ran into the lifeboat and capsized it, with the

result that four of the crew were drowned. The

survivors of the St. Mathieu were landed at La

Palice on the morning of the eighth of January and

later the captain was awarded the Military Medal and

all of the members of the crew were cited in orders.

At about noon on the tenth of

October, 1917, the captain of the French ship

Transporteur, was exchanging semaphore signals with

the Afrique II, a French patrol boat, when he

noticed in the sunlight, at a distance of about

three hundred meters, the wake of a torpedo coming

toward him, a little forward of the beam. He

immediately steamed "hard-right," reversed his

engine and warned his escort by whistle.

Unfortunately his action, although prompt, proved

unable to avoid the path of the torpedo, which,

striking the ship at the water line, caused a

terrific explosion and brought down the forward

mast. The ship listed and forty seconds later the

water was almost even with the forecastle. For a

brief period the vessel remained standing almost

perpendicular, its propeller continuing to turn

rapidly in the air; then perpendicularly and like an

arrow shot from a great height, it dived into the

sea. Of the twenty-four men comprising the crew,

twenty-one survivors were rescued by the Afrique II,

while swimming in the wreckage.

The engagement of the French

steamer La Ronce with an enemy submarine, is another

example of French fortitude. Sighting a torpedo on

the port beam headed in a direction which would

undoubtedly bring it up opposite the engine-room,

the officer of the deck put his rudder "hard-left"

with the result that the torpedo exploded by No. 4

hatch, tearing a large hole in the side of the

vessel. The stern gun being destroyed, the captain

manned his forward gun, but could not locate the

submarine. Little by little, the ship settled by the

stern and the after part of the deck being

submerged, the water began to enter the engine-room

through the hatchways. Seeing that it was impossible

to keep his vessel afloat much longer, the captain

ordered her to be abandoned and the crew embarked in

boats in a heavy sea. As several of the boats had

been destroyed by the explosion, those that were

launched were overloaded and when the order was

given by the captain to " push offf," he realized

their crowded condition and remained on board the

sinking ship with the engineer officer and radio

officer and with them went down with the ship.

The Voltaire II was bound for

Nantes. Sailing from Gibraltar on the eighth of

December, 1917, the captain opened his secret;

instructions, issued in the event of his leaving the

convoy, and proceeded about one hundred and forty

miles in a new direction. The night was very dark

and the ship was without lights. At twenty minutes

to four a torpedo struck the ship near the stern,

tearing loose the mainmast and throwing it on the

bridge. The wireless antenna was carried away by the

falling mast and the water rose so rapidly that it

became impossible to use the auxiliary antenna. Due

also to the rapidly rising water, the boats were

jammed against the davit-heads and with the

exception of the port whaleboat, which was launched

with four men, none of them could be lowered. The

ship disappeared in three minutes, taking with her

the captain and the greater part of the crew. About

twenty-four sailors were rescued by the whaleboat.

Sail was made and the boat was headed for Belle-Ile,

in a heavy sea. It was cold and the boat was so

overloaded that it was difficult to keep it afloat.

The men for the most part, were about half dressed

and became rapidly exhausted. During the evening of

the twelfth, the light of Penmarch was seen,

but soon after the mast broke and it became

necessary to continue with the oars. A few hours

after, they passed a convoy and later a single ship,

but their signals of distress were unnoticed.

Finally, at noon they were sighted by the French

trawler which rescued the men and took them to

Lorient. Two died from the cold and exposure. At no

time before or after the torpedoing did anyone see

the submarine or its periscope.

| |

The British mystery ship Dunraven, under fire from

a submarine. The white smoke at the stern is from

an exploding shell

|

|

The

Dunraven sinking

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The

Philomel

(British) sinking after being torpedoed

|

|

The

last of the Philomel

|

|

On her way from St. Malo, to join a

convoy of sailing vessels, the French schooner

Jermaine was attacked by a submarine which opened

with four shells and followed with a volley of fire,

meanwhile circling the sailing vessel. The Jermaine

was ably commanded by a former sergeant of colonial

infantry who promptly organized the crew and

prepared to defend the ship at all hazards. The sea

was running so high that it was impossible to see

the submarine except at rare intervals. Climbing

into the rigging, in order personally to watch the

shots which were fired by the Jermaine whenever the

enemy became visible between the troughs of the sea,

the captain tacked to run with the wind in order to

make use of his two guns. So accurate was the fire

of the sailing ship that at the fourth shot from the

Jermaine, the submarine abandoned the struggle and

rapidly changed its course.

The British ship Austradale left

Milford Haven on the sixteenth of October, 1917, in

a convoy of twenty-five ships, proceeding in columns

of eight. Her position was No. 1 in the left column.

About three days out, the Austradale sighted at a

distance of approximately three miles, an object

which appeared to be a capsized fishing boat. The

captain gave the signal “Suspicious object sighted "

and now believes it was put there by the submarine

in order to divert his attention from the subsequent

attack which came from the opposite side. At all

events, while watching the object, the ship was

suddenly torpedoed on the port side, on a line with

the engine-room, and sank in three minutes. The

forty-five surviving members of the crew embarked in

a whaleboat and two dinghies. The boats were well

provided with food and as danger was imminent, the

convoy proceeded and the small boats were soon lost

in the night. For seven days, the crew navigated

their small craft in heavy seas, covering a distance

of 330 miles. During this period, one man became

insane and jumped into the sea. Leaks developed

which required constant baling and reduced the

survivors to a state of almost complete exhaustion.

Two of the dinghies reached Port Kerrel, but one of

the men later died of exhaustion. The whaleboat,

containing twenty-four men, was never heard from.

On September 16, 1918, the Rambler

rescued forty-one survivors from the British S. S.

Philomel and carried them into Lorient. The Philomel

was the leading ship of the right column of a

south-bound convoy from Brest to La Palice and the

Rambler was one of the escorting vessels. No

submarine or torpedo was seen at any time, nor was

the submarine detected by the listening devices. The

Philomel was struck on the starboard side, under the

bridge, and, following the explosion, she swung to

starboard out of the column and was immediately

abandoned. At 6:14 P.M, about thirty minutes after

being struck, the Philomel began to sink by the bow,

taking a very sharp angle until her bow seemed to

rest on the bottom. A minute later she disappeared

from sight, with steam escaping and her whistle

blowing.

Relatively few were the disasters

which befell American troop and store ships. And of

those sinkings which occurred, the large majority

were among the empty vessels homeward bound. Perhaps

the slightly inferior escorts which took out the

returning ships may have been the reason, but it is

more probable to suppose that the enemy found a

resistance on the part of the eastwardbound convoys

which would have been unmeasurably intensified by

the knowledge, on the part of the officers and crews

of both escort and convoy that American lives other

than their own and property necessary for the

prosecution of the war were resting in their

protection below the vessels' decks.

Particularly to the credit of all

concerned, was the salvaging of the ships West

Bridge, Westward Ho, and Mount Vernon. Only through

the indomitable perseverance of the officers and men

were these wounded vessels brought into port. The

story of their rescue is one of the silent epics of

the war.

The torpedoing and rescue of the

Westward Ho has been told in a previous chapter but

the incidents attendant on the attacks on the West

Bridge and Mount Vernon deserve mention in this

narrative.

There was unusual activity of enemy

submarines to the west of the Bay of Biscay during

the early part of August, 1918, and three vessels,

the U. S. S. A. C. T. Montanan of 6,659 tons gross,

the U. S. S. A. C. T. West Bridge of 8,800 tons

gross, and the U. S. S. A. C. T. Cubore of 7,300

tons gross were torpedoed.

The Montanan was struck when

proceeding in convoy at about 7 P.M. on August 15

and sank at 3 P.M. on the following day. The yacht

Noma, acting in the escort, took aboard eighty-one

survivors and reported that five of the personnel

were missing.

The U. S. S. A. C. T. Montanan

reported that three torpedoes were fired. Of these

she succeeded in dodging two, but was hit by the

third torpedo abreast of the after end of the

engineroom. The explosion smashed a boat and put the

radio completely out of commission. The ship settled

rapidly and it was in abandoning ship that the two

members of the armed guard were drowned.

At one o'clock in the morning on

August i6, the West Bridge was torpedoed within a

few miles of the spot where the Montanan was sunk.

She was proceeding in the same convoy, but had

fallen back due to engine trouble and for some hours

prior to her attack her engines had stopped

entirely. While lying in this extremely vulnerable

position, she was struck by two torpedoes in quick

succession, the second torpedo being visible at the

moment when the first torpedo went home. The

Concord, Smith, and Barnegat were despatched to her

assistance, but the destroyers Drayton and Fanning

which were standing by her, were required to leave

her on the afternoon of August 16 to join a convoy.

One officer and three men were missing, probably

killed by the explosion in the engine-room. The

ninety-nine survivors were taken into Brest by the

U. S. S. Burrows.

At the time of the arrival of the

West Bridge in Brest, it was calculated that only

one per cent of the normal buoyancy of the hull

before loading, remained. The calculated buoyancy

having been reduced from ten thousand tons to one

hundred tons.

The Cubore was struck on August 15

at ten o'clock in the evening and sank an hour

later. Fifty survivors including the captain and the

armed guard were taken off by the French gunboat

Etourde.

The Westover of the Naval Overseas

Transportation Service was torpedoed on the morning

of the eleventh of July, 1918, and sank forty

minutes later. The vessel left New York in convoy,

but it had been forced to drop behind because of

engine troubles; due primarily to the inexperience

of her engineer force with turbine machinery. These

troubles were later overcome and at the time she was

torpedoed, the Westover was making her speed and

endeavoring to overtake the convoy. She was struck

by two torpedoes. The first struck on the starboard

side, abaft No. 3 hatch and the second aft on the

port side. Her cargo contained 1,000 tons of steel,

2,000 tons of flour, 10 locomotives and 14 motor

trucks, a deck load of 400 piles and 250 tons of

second-class mail.

The Warrington arrived on the scene

within a few hours of the time of the sinking of the

vessel. Five boats containing the survivors made the

French coast in the vicinity of Brest; but three

officers and eight enlisted men were lost.

On September 5, 191 8, the U. S. S.

Mount Vernon, westward bound from Brest for the

United States was proceeding in company with the U.

S. S. Agamemnon. At a little before eight in the

morning, her watch sighted a submarine forward of

the beam, in a position between the Mount Vernon and

the Agamemnon. The Mount Vernon immediately dropped

five depth charges and fired one shell in the

direction of the periscope. Ten seconds later the

ship received the torpedo amidships on the starboard

side, between fire-rooms three and four, killing

thirty-five of the engine and fire-room force and

wounding twelve. The Mount Vernon accompanied by

three destroyers started to return to Brest at a

speed of six knots, which was later increased to

fourteen knots, arriving at Brest about midnight;

the Agamemnon continued her voyage westward.

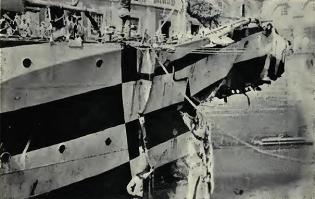

| |

The

bow of the von Steuben after collision

with the Agamemnon

|

|

The

Mount Vernon in dry-dock showing the hole torn in

her

side by a torpedo

|

|

On receipt of the news of the

disaster, the Sigourney, with two other destroyers

and the U. S. S. Barnegat and Anderton were sent out

from Brest to assist in escorting the Mount Vernon

into port. At the time of her departure from Brest,

the Mount Vernon was drawing twenty-nine feet aft.

On her return she was drawing thirty-nine feet, five

inches aft and thirty-three feet forward; four of

her fire-rooms being completely flooded. She was

also listing 10° to port. From the time the torpedo

struck the ship until its arrival in dock, in Brest,

all of the officers and men worked untiringly on

pumps, handy-billies, and buckets, putting

additional shores on the bulkheads and reinforcing

hatches and doors. The Mount Vernon docked at Brest,

repaired and later was again put into commission.

The U. S. S. Buenaventura, an

American cargo transport of 8,200 tons, sailed from

Le Verdon in convoy on the fourteenth of September,

1918, and was struck by two torpedoes and sank in

six minutes, shortly after the convoy had been

dispersed and the escort had left on its way to the

rendezvous of the incoming convoy. So sudden was the

attack and the final plunge of the vessel that only

three boats were able to get away. All reports

indicate that the behavior of the officers and crew

was excellent; the captain devoted his entire

efforts to save his crew, declining to the very last

to make any effort to leave the sinking ship. A

motor sailer and another boat which succeeded in

getting away were picked up by the French destroyer

Temeraire, and brought into Brest, and a third boat,

containing the commanding officer, the executive

officer, and twenty-seven men reached Corunna,

Spain, after a number of days at sea.

One of the last cargo carriers to

meet destruction by a submarine was the U. S. S. A.

C. T. Joseph Cudahy, which was struck by two

torpedoes on the seventeenth of August, 1918. The

first torpedo struck the Cudahy in the fuel tank;

the second in the engine-room. Two submarines took

part in the action. After abandoning ship, the

captain of the Cudahy was taken on board one of the

submarines and questioned concerning the destination

and whereabouts of the convoy. Sixty-two members of

the crew were lost.

A study of the circumstances,

surrounding the torpedoing of the Justicia,

President Lincoln, Covington, Tuscania, Antilles,

and Tippecanoe, as well as a number of other

vessels, shows that all of these were sunk by

quartering shots. This indicates that the probable

procedure of the submarine was to submerge in

advance of the convoy and at right angles to its

course, having estimated from previous bearings the

convoy's general direction and the probable nature

of the zigzag, emerging when its hydrophones

indicated that the convoy had passed. From such a

position, the danger to the submarine would be

materially reduced, inasmuch as the convoy would be

soon in advance of the position occupied by the

submarine; provided, of course, that no escort was

occupying a position astern of the convoy. High

speed on the part of the vessels attacked, would

naturally, from this supposition, prove a great

asset of safety.

Large as were the dangers due to

the submarine, it is to the credit of the yachts and

destroyers on the French coast that the record of

the American debarkation in France was achieved, and

also, that of the ships which were lost, the great

majority were homeward bound and hence empty of

troops or cargo.

CHAPTER

IV

THE

CONVERTED YACHTS

It is fair to presume that in the

years to come the part which the United States Navy

played in the Great War will be in a large part

judged by the safe conduct of troop and store ships

to and from the coast of France. As the territory

stretching from Switzerland to the Belgian coast

formed the front line of our land forces, so the

fighting front of the United States Navy may be

considered, in the large part, the western coast of

France.

During the long months of submarine

warfare bodies of troops were safely transported

across the Atlantic, escorted through the submarine

danger zone and landed on foreign soil, in numbers

never exceeded by any similar instance in the

history of the world. Not only was an army thus

convoyed in safety, but, and of equal importance,

were the vast quantities of stores necessary for its

subsistence and for the prosecution of the war

carried safely through an area infested with enemy

submarines. To meet the enemy two classes of vessels

were assigned to the work. Of these the destroyers

were by their construction best fitted for the duty