Dar-es-Salaam

was left alone for over a month,

but the Senior Naval Officer was

never satisfied that the

obstruction really blocked the

fairway, and he had even less

faith in the pledge of the

governor that the ships would

not try to escape. On 28th

November H.M.S. Fox and Goliath,

with two small vessels in

company, anchored off Makatumbe

Island, which lies a few miles

out to sea from Dar-es-Salaam,

and hoisted the international

signal to the people ashore to

send off a boat. It must be

explained that the situation had

changed completely, since those

early war days, when the Astrea

paid her visit there. The

exploits of the Konigsberg had

clearly indicated that East

Africa was not to be excluded

from the war zone, whatever

might be the pledges of the

local governors; and then came

our military disaster at Tanga,

when we altogether

underestimated the resistance

likely to be offered by the

enemy, with the result that we

came off with 800 casualties -

and some valuable experience.

Moreover, the Navy had been busy

in the Rufigi River, bottling up

the Konigsberg, so that when

they arrived off Dar-es-Salaam

they were there for business,

and in no mood for anything

else.

At

the same time it must be

remembered that Dar-es-Salaam

purported to be an undefended

harbour, and was entitled to be

treated as such, until there was

evidence of hostile intentions

on the part of its inhabitants.

So the Senior Naval Officer

hoisted the signal for a boat

and waited on events. After an

hour or so a motor-boat came out

of harbour, flying a flag of

truce, and brought up alongside

H.M.S. Fox. In it were the

acting governor, the district

commissioner, and the captain of

the port, who all came aboard,

and were conducted to the Senior

Naval Officer's cabin. Mr. King,

formerly British Consul at

Dar-es-Salaam, acted as

interpreter.

The

Senior Naval Officer reminded

the German officials that the

ships in Dar-es-Salaam Harbour

were all British prizes, and

informed them that he had come

to inspect these ships, to take

such steps as might be necessary

to disable them, and to withdraw

from the harbour or disable any

small craft which might be used

against the British forces. Now,

one of the ships in the harbour

was the s.s. Tabora. which had

been painted as a hospital ship,

and according to the Germans was

being used as such, At Lindi we

had found the s.s. Prasident

painted in the same way, and had

been told the same yarn - that

she was being used as a hospital

ship - but we had discovered by

inspecting her that the yarn was

all a tissue of lies, and that

the ship was palpably a collier,

which had recently been used for

supplying the Konigsberg. So we

were naturally suspicious about

the Tabora, and the Senior Naval

Officer pointed out to the

German officials that she had

not complied with the

international regulations,

necessary to convert her into an

accredited hospital ship. He

added, however, that he had no

wish to cause suffering to any

sick persons, who might be

aboard her, and that he would

send a medical officer to

inspect her. He would also send

a demolition party to disable

her engines, but nothing should

be done in this direction if the

medical officer was of opinion

that it would be injurious to

any of the patients on board. He

further assured them that no

damage should be done to the

town or its inhabitants, so long

as no opposition was offered to

the working parties, whom he was

going to send into the harbour,

to do what was necessary for the

disablement of the engines of

the various ships.

The

acting governor was obviously

very uncomfortable and ill at

ease. All he could say was that

he would like to confer with the

military authorities at

Dar-es-Salaam. Military

authorities in an undefended

port seem to be rather out of

place, but the Senior Naval

Officer waived the point, and

merely told him that he would be

given a good half-hour or so

after landing, before the

British boats entered the

harbour. The governor then asked

rather a curious question. Would

these boats carry on their

operations under the white flag

? The Senior Naval Officer,

somewhat surprised at such a

question, naturally answered in

the negative, and at that the

German officials took their

departure and returned to the

town.

A

good deal more than the

half-hour's grace was allowed

before a steam-cutter was sent

in to sound and buoy the channel

into the harbour. It was noticed

that two white flags had been

hoisted on the flag-staff over

against the look-out tower at

the entrance, and these floated

conspicuously in the breeze, so

that they could be seen from all

directions. The occupants of the

steam-cutter, as soon as they

rounded the bend, noticed a lady

driving in a carriage drawn by a

pair of horses along a road

close to the water's edge.

Everything looked so peaceful

that one would have imagined

that our dear German brothers in

Dar-es-Salaam had never heard of

the war.

When

a channel had been buoyed, one

of the tugs (the Helmuth),

accompanied by the Goliath's

steam-pinnace, was ordered to

proceed into the harbour with

the demolition party. The other

tug (the Duplex), owing to some

engine-room defects, did not

enter the harbour, but lay at

anchor about two miles from it.

The two ships. Fox and Goliath,

were about five miles from the

shore, and those on board them

were taking only a languid

interest in the proceedings, for

the two white flags at the

lookout tower were flaunted in

their faces, and war seemed to

them a very tame affair after

all. It is very easy to be wise

after any event, and to say that

this or that precaution should

have been taken, but it must be

borne in mind that there were

the two white flags, conspicuous

to everyone, and the enemy was

not a barbarous tribe from the

African jungle, but purported to

be a civilised European people.

So

the Helmuth proceeded up the

harbour to where two ships,

called the Konig and

Feldmarschall, were lying, and

the demolition party boarded the

Konig, and proceeded to destroy

her engines by placing an

explosive charge under the

low-pressure cylinder, followed

by another one inside it. The

crew of the Konig appeared to

consist mainly of Lascars, and

the only officers on board were

the chief engineer and the

fourth officer. From these it

was learned that all the rest of

the officers and men were

ashore, and at the time it did

not occur to Commander Ritchie,

who was in charge of the

demolition party, that there

could be anything unusual in

this circumstance. He ordered

all the Konig's crew to go down

into the ship's boats, informing

them that they were prisoners of

war.

Shortly

afterwards the Goliath's

steam-pinnace came up, bringing

some more men of the demolition

party, with Lieutenant-Commander

Paterson in charge. Commander

Ritchie instructed this officer

to complete the disablement of

the engines of the Feldmarschall

and Konig, while he himself went

farther up the creek in the

Helmuth to another ship, called

the Kaiser Wilhelm II. The

Helmuth, however, ran on the

mud, and had some difficulty in

getting off, so Commander

Ritchie took her back to the

Konig, and tried the

steam-pinnace in place of her.

In this he successfully reached

the Kaiser Wilhelm II, disabled

her engines, and destroyed two

lighters that were lying near

her. But what first gave him a

sense of uneasiness was the fact

that the Kaiser Wilhelm II was

absolutely deserted. Her crew

were nowhere to be seen, but on

her deck were found some Mauser

clips - one containing three

bullets with the pointed ends

sawn off - suggesting that the

ship's crew had recently been

busy overhauling their rifles.

The absence of the officers and

white ratings from the other two

ships now assumed a new

significance.

Lying

near the ship were five other

lighters, and it occurred at

once to Commander Ritchie that

it might be useful to have one

of these on each side of the

steam-pinnace, by way of

protection, for there was

evidently mischief of some kind

or other brewing.

The

other three lighters he towed

astern, and, thus encumbered,

the pinnace made the best speed

she could down the creek. As she

passed the Konig and

Feldmarschall, Commander Ritchie

saw that the Helmuth had already

started her return voyage, and

though he scrutinised the two

ships carefully through his

glasses, he could see no signs

of anyone in either of them. So

he proceeded down the creek, but

found that the pinnace made such

slow progress that he was

finally obliged to drop the

three lighters astern, only

retaining the two which were

made fast on either side of the

pinnace.

In

order to keep to the

chronological order of events,

we must now return to the

Helmuth and Lieutenant-Commander

Paterson. He was engaged with

his demolition party on the

engines of the Konig and

Feldmarschall, and in the

meantime some thirty prisoners

from the Konig were sitting in

the two boats belonging to that

ship. Lieutenant Orde had

received instructions from

Commander Ritchie to proceed

down the harbour, towing these

two boats, to stop at the s.s.

Tabora and put Surgeon Holton

aboard there to inspect the

ship, and then proceed out to

sea and deliver his prisoners

over to the Duplex, afterwards

returning to the Tabora to pick

up Surgeon Holton. This, at any

rate, was how Lieutenant Orde

understood his instructions, and

he not unnaturally concluded

that Lieutenant-Commander

Paterson and his working party

intended to return in the steam

pinnace with Commander Ritchie.

It is not very clear why he

should have thought that the

sole object of his returning to

the Tabora, after the safe

delivery of his prisoners, was

to pick up Surgeon Holton, for

it had always been intended that

a demolition party should board

the Tabora, and should disable

her engines if Surgeon Holton

was of opinion that this could

be done without injury to any of

the patients. Possibly, however,

Lieutenant Orde was unaware of

this arrangement.

It

may here be stated that the

Tabora was genuinely being used

as a hospital ship. There were

doctors and nurses and some

wounded men in her, and she was

fitted with cots and other

hospital equipment.

And

now we must return to H.M.S. Fox

and the Senior Naval Officer. It

was late in the forenoon when he

ordered the steam-cutter

alongside, and, accompanied by

an army staff officer, went in

to have a look at the sunken

dock at the mouth of the

harbour. It was a morning of

bright sunshine, and through the

clear water he could see the

obstruction lying about ten feet

below the surface, but, without

sounding, it would be difficult

to say whether or not it

effectually blocked the channel.

He then thought he would go

round the bend, and see what the

harbour looked like, and how the

demolition parties were getting

on. He gave the order to the

coxswain to go ahead, and leaned

comfortably back in the

sternsheets of the boat,

enjoying the pleasant sunshine

and possibly wondering why the

Germans had hoisted two white

flags on the flag-staff, when

one would have answered the

purpose.

Suddenly

the sharp crack of a rifle was

heard, and a bullet struck the

water on the port side of the

steam-cutter. Next moment a

blaze of rifle fire came from

either bank, and bullets began

to rain against the sides of the

boat. The hottest fire seemed to

come from the vicinity of the

flag staff, where the two white

flags still floated in the

breeze. "Lie down everyone,”

shouted the Senior Naval

Officer, and to the coxswain he

gave the order “Hard-a-port.”

The bullets were whistling over

their heads, were pouring into

the boat, and were piercing the

thin iron plates, which had been

rigged for the protection of the

boiler and of the coxswain in

the sternsheets.

The

stoker tending the fire was

dangerously wounded, but

Lieutenant Corson ran forward

and took his place. In the after

part of the boat a seaman was

hit in the head, and the

coxswain had a bullet through

his leg, but pluckily stuck to

his job, although another wound

caused the blood to pour from

his mouth. “That's nothing,

sir,” he said. "I'm all right.

We shall soon be out of the

channel.”

No

one in the boat was armed, and

so there was no way of replying

to the fire. To make matters

worse, speed had slackened owing

to the furnace having been

neglected before it was noticed

that the stoker was wounded. But

the efforts of Lieutenant Corson

soon increased the steam

pressure, and after a while the

boat got beyond the danger zone.

The coxswain stuck to his post

in spite of his wounds, and

eventually brought the boat

alongside the Fox about half

-past one in the afternoon.

Stoker Herbert T. Lacey died of

his wounds.

Immediately

afterwards the firing broke out

again, and the Senior Naval

Officer saw that the Helmuth was

coming through the neck of the

harbour, towing astern of her

two boats full of prisoners. She

had put the doctor on board the

Tabora, and was on her way to

the Duplex to hand over the

prisoners, when field-gun,

rifle, and machine-gun fire was

opened on her from the north

bank. The coxswain was

immediately wounded, and his

relief had no sooner taken his

place than he, too, was wounded.

Then Lieutenant Orde. who was in

command, received a wound, but

the worst piece of bad luck was

that a bullet struck the

breech-block of the Helmuth' s

only gun - a 3-pounder - and put

it out of action, so that she

became as defenceless as the

Fox's steam cutter had been. The

bullets came pouring into her,

and some of them punctured the

steam pipes, with the result

that there was a heavy escape of

steam, and the speed of the tug

slackened considerably. There

was a certain amount of grim

satisfaction in seeing a stray

bullet hit one of the boats

astern, and wound a German

prisoner, but this was the only

consolation to be derived by the

Helmuth's unfortunate victims.

The

Senior Naval Officer in the Fox

promptly signalled to the Duplex

to open fire on the shore with

her 12-pounder, and both the Fox

and Goliath bombarded the shore

whence the enemy's fire seemed

to be coming. This had the

desired effect of causing some

slight abatement, and after a

while the Helmuth got beyond the

danger zone. The Goliath was

then ordered to put a few shells

into the governor's palace,

which she proceeded to do with

one of her 12-inch guns, and

after two or three rounds the

palace was reduced to a heap of

ruins. Then there came a lull in

the proceedings, and one would

have supposed that the Germans

hiding in the vicinity of the

look-out tower would have

occupied their leisure in

hauling down the white flags

from the flag-staff. But the

white flags continued to float

serenely in the breeze, and the

Germans beneath them stood

waiting for their next victims.

We

must now return to the

steam-pinnace and Commander

Ritchie. Having satisfied

himself that there was no one

aboard the Konig or the

Feldmarschall, he continued his

way down the harbour, and, as

already related, he dropped the

three lighters which were in tow

astern, in order to increase

speed. When he was approaching

the Tabora he saw Surgeon Holton

put off from her in a boat, and

head towards the steam-pinnace.

He had just eased down the

engines to enable the doctor to

come alongside, when a heavy

fire was opened on him from both

sides of the harbour. The crew

of Surgeon Holton' s boat took

fright, and began to pull back

to the Tabora. At this the

steam-pinnace tried to get up to

the boat, but with her two

lighters in tow on either side

of her, she was difficult to

steer, and finally had to

abandon the attempt. But the two

lighters proved to be her

salvation, for some field guns

were now firing shells at her,

and without the protection of

these lighters she must

inevitably have been sunk.

As

she rounded the bend the shot

and shell came at her from all

directions, and though the Fox

and Goliath again opened fire to

cover her retreat, it did not

seem to make much appreciable

difference. For the enemy were

well hidden among the palm

trees, and from the ships, lying

five miles out to sea, it was

impossible to locate them. Two

men in the steam-pinnace were

hit almost at the outset; one of

them was the coxswain. Petty

Officer Clark, whose place was

taken by Able Seaman Upton. Then

Upton was hit, and Clark, whose

wound had been temporarily

dressed, tried to resume his

place at the wheel, but fainted

away from loss of blood. This

was the critical moment, for the

narrow entrance of the harbour

and the sunken dock still lay in

front of them, and there was

need of a cool head and a steady

hand to steer the boat through.

Commander Ritchie had by this

time been wounded in several

places, and was in considerable

pain, but he saw that the only

chance of escape lay in skilful

steering, and so he took the

wheel himself. Amidst the

ceaseless shower of bullets

whistling over his head and

singing past his ears, he

piloted the boat through the

neck of the harbour, and had

just got clear of it when a

bullet struck him in the leg. It

was his eighth wound;

simultaneously the boat ran on a

sand-bank, and the commander

fainted. Fortunately, however,

the worst of the danger was now

over; the boat got afloat again

without much trouble, the two

lighters, having served their

purpose, were slipped, and in

less than an hour the boat

reached the Fox. In addition to

the commander, one officer and

five men were wounded.

Throughout

the whole or these proceedings,

the two white flags flew

majestically from the flag-stall

- the emblems of Germany's high

ideal of universal peace and the

brotherhood of man. But the

whole of the tale of treachery

is not yet told. It soon became

known that Lieutenant-Commander

Paterson and his section of the

demolition party were missing.

The party included Lieutenant

(E) V. J. H. Sankey, Chief

Artificer Engineer W. E. Turner,

one chief petty officer, and

seven other ratings. The

solution of the mystery of their

disappearance was only revealed

when these officers and men were

released from their captivity

nearly three years later. It

appears that while the party was

at work in the Konig,

Lieutenant-Commander Paterson

became aware that armed troops

were on the river-bank in a

position commanding the deck of

the ship. When the firing

started lower down the harbour,

he realised at once that they

were in for trouble, and, in

fact, he had anticipated it. He

therefore kept the whole of his

party down below, fully

expecting that Commander

Ritchie, when he returned with

the steam-pinnace, would come

alongside the ship. Presently he

saw on the other side of the

estuary two large lighters, with

the funnel of a small steamboat

just appearing above them. At

first he failed to recognise

that this was the steam-pinnace

of his own ship, but when it had

steamed straight past the Konig,

and he was able to get a better

view of it, he realised the

awful truth that there had been

some misunderstanding, and that

he and his party were left in

the lurch. He knew that if he

showed himself on the upper deck

the Askaris would open fire on

him, and he knew that Commander

Ritchie would not be able to

hear his voice, unaided by a

megaphone. There was only one

chance that if they all kept

very quiet the troops on the

bank might think they had left

the Konig, and under cover of

night they might be able to find

a boat and slip out of the

harbour. It was a forlorn hope,

and unfortunately it was doomed

to disappointment. In the early

evening the Germans came and

took them all prisoners.

On

30th November 1914 the Senior

Naval Officer addressed a letter

to the governor of

Dar-es-Salaam, recapitulating

what had taken place, and

warning him that the town would

be subjected to bombardment, but

the Tabora would be spared, not

as an accredited hospital ship,

but because there were reported

to be wounded men in her. The

governor's reply (which was

somewhat belated) was a truly

marvellous piece of composition.

First of all he said that though

he had agreed to the British

visiting the ships in the

harbour, he had never agreed to

allow them to disable the

engines; then he stated that the

British boats came into the

harbour filled with armed men;

and finally he excused the

presence of the white flags by

saying that there was no

possibility of hauling them down

because the fight was so

intensive. Apparently his idea

of an intensive fight is hiding

behind a palm tree, and potting

at defenceless men in open

boats. The letter was a poor

production, even as a specimen

of German mendacity.

At

half-past two that afternoon

there was another "intensive

fight” in Dar-es-Salaam, in

which the government buildings,

the warehouses, the railway

stations, the customs house, and

the barracks received special

attention. The debris of these

buildings was seen flying above

the tree-tops, but only two

small fires were started, as

most of the houses were built of

coral slag. But it is a fair

surmise that, by the time the

entertainment was over, the

governor and people of

Dar-es-Salaam had had enough of

“intensive fighting.”

Commander

Henry Peel Ritchie, for his

heroic conduct in taking the

wheel of the steam-pinnace, and

bringing the boat out of

harbour, after he had received

eight wounds, was awarded the

Victoria Cross.

CHAPTER

II

BOTTLING

UP THE "KONIGSBERG"

(click

map to enlarge)

During

the month of September 1914

H.M.S. Pegasus - an old light

cruiser of about 2,000 tons -

put into Zanzibar Harbour to

repair her boilers. Now Zanzibar

is a British protectorate, but

this fact afforded no guarantee

at that time that the island was

not swarming with German agents,

and lying as it does not far

from the mainland of German East

Africa, it followed as a matter

of course that the Germans were

kept fully informed as to what

was happening at Zanzibar. By

means of wireless stations,

which were quite plentiful down

the coast of German East Africa,

they were able to communicate

interesting news to any of the

German cruisers that were

roaming the seas in those days.

And so it came about that the

German cruiser Konigsberg

received a message to say that a

small British cruiser was lying

disabled in Zanzibar Harbour -

an old third-class cruiser with

out-of-date guns, that could not

be expected to put up any kind

of a fight, and could be easily

outranged by the German guns.

Here was just the kind of job

the Konigsberg enjoyed, and so

on 20th September she pounced

down on her prey, and very

quickly pummelled the poor old

ship to pieces.

Out

of the destruction of the

Pegasus the only compensation to

be gained was the knowledge that

the elusive Konigsberg was oil

the East African coast, and it

was a fair assumption that she

was receiving her supplies of

coal and stores from the shore,

by means of German merchant

vessels. There were several of

these vessels dancing attendance

on the raider, and, according to

information received, one of

them was called the Prasident,

and another the Somali. There

were other ships in

Dar-es-Salaam Harbour, which

were under suspicion, but the

Germans had themselves blocked

the mouth of that harbour by

sinking an obstruction, and for

the present we were content to

believe that the obstruction was

effective, and to leave the

Dar-es-Salaam ships out of the

account. When, therefore, three

British cruisers were told off

to search for the Konigsberg,

they worked upon the basis that

the discovery of the Prasident,

or the Somali, or both, might be

of material assistance.

The

search was not an easy one,

because the coast for the major

part is fringed with thick belts

of palm trees, behind which the

harbours, formed by the

estuaries of the rivers, wind

away out of sight. Thus at

Lindi, near the southern

extremity of the colony, the

Weymouth had a look at the outer

harbour, which was empty, but

could see nothing of the inner

harbour behind the palm trees,

nor of the river beyond it, and,

owing to shallow water, was

unable to approach to such a

position as would command a view

of these. But a few days later

the Chatham called at Lindi, and

sent in a steamboat, armed with

a maxim-gun. Commander

Fitzmaurice went in with the

steamboat, carrying a letter to

the governor of Lindi, which was

only to be delivered if it were

found that a German ship of any

kind was lurking in the inner

harbour. The letter contained an

order to the governor, to send

out to sea any ships that might

be in his harbour, and gave him

half an hour to carry out this

order, before anything

unpleasant should happen to him.

Now,

as soon as the steamboat turned

the corner, the first thing to

meet the gaze of Commander

Fitzmaurice was the Prasident

moored about three and a half

miles up the river. But he had

to rub his eyes to make sure of

her, for, instead of a ship

looking like a collier, or even

like an ordinary merchantman, he

saw what looked uncommonly like

a hospital ship. At her

mast-head the Geneva Cross was

floating in the breeze, and on

her side was painted a large

white cross. And yet she was not

by any means perfect in her

make-up, for she had not painted

her hull white, nor had she the

broad band of either green or

red running from stem to stern,

which is used to denote the

hospital ship. For once the

Teuton lacked thoroughness in

his methods.

Next

came a boat from the shore,

flying a white flag, and in it

sat the governor's secretary, to

whom Commander Fitzmaurice

delivered the letter. Then came

an interval of waiting for an

hour or two, while the governor

was considering his reply.

Presently the secretary came off

again in the boat with the white

flag, and the governor's reply

in his best official German was

duly conveyed to the Senior

Naval Officer. In a tone of

injured innocence the governor

asked plaintively how could he

comply with the Senior Naval

Officer's order. The Prasident

was the only ship in the

harbour, and how could he be

expected to order a hospital

ship to go to sea ? It was

affording shelter to the women

and children of Lindi, and to

all the sick men of Lindi; to

send it to sea would be an act

of barbarism. Moreover, its

machinery was incomplete, and

the wheels would not go round,

so the Senior Naval Officer

would see at once that it was

quite out of the question to

send it out of the harbour.

Meanwhile,

however, the Senior Naval

Officer had been writing another

letter to the governor, which

proved to be a very suitable

reply. He pointed out that the

name of the Prasident had not

been communicated, either to him

or to the British Government, as

a hospital ship, in accordance

with the terms of the Hague

Convention, and that her hull

had not been painted as the hull

of a hospital ship should be

painted. He then briefly

informed the governor that he

was sending an armed party to

board her, and, if possible, to

bring her out of the harbour,

or, if this proved to be

impossible, to disable her

engines.

That

was the end of the negotiations;

the governor made no further tax

upon his powers of romance, but

bowed to inexorable Fate. And so

the armed party was sent into

the harbour in a steamboat, and

went on board the Prasident.

There are still some

strange-minded folk who cling to

their faith in the honesty of

purpose of the much-abused

German; it may come as a shock

to them to learn that the

hospital ship Prasident had no

cots, no medical equipment of

any kind, no doctors, and no

nurses; nor were there any sick

men on board, nor any women, nor

any children. There were,

however, unmistakable traces of

the collier to be seen

everywhere about her; and it was

evident that she had been

recently employed in this

capacity. There are other

strange-minded folk who will

exclaim, “How clever those

Germans are ! “But when they

come to think it out, they will

see that there was nothing

remarkably clever in painting a

white cross on a collier, when

she was threatened with capture

or disablement. It was a

childishly simple trick, as most

of the German tricks are.

The

Prasident' s engines were

disabled by the boarding party,

and they brought away with them

a few useful mementoes, such as

a chronometer, a set of charts,

a set of sailing directions, and

some compasses. So ended the

career of the Prasident, collier

and supply ship to the German

raider Konigsberg.

Nearly

a fortnight later, on 30 th

October, the Chatham lay at

anchor off the Rufigi River

delta, and sent in a steamboat

to the shore, in quest of

information. Three natives were

seen wandering about among the

palm trees, and were persuaded

by cogent arguments that it was

their duty to pay an official

visit to H.M.S. Chatham. In

other words, they were brought

off to the ship in the

steamboat, and through the

medium of an interpreter they

unfolded their tale. Yes, there

were two ships lying up the

Rufigi River behind the forest

of cocoanut palms, and one of

them had big guns, that made a

big noise. Boom ! The other was

like a handmaiden to the fellow

with the guns - like a good and

faithful wife to him, who waited

on him and gave him ghee and

rice and dhurra when he was

hungry. They described the ships

in their own language, and the

description was good enough to

set all doubts at rest. The

Konigsberg and the Somali had

been traced to their lair at

last. From the Chatham's foretop

it was just possible to see the

masts of two ships sticking up

above the palm trees, but

nothing could be seen of their

hulls. One useful piece of

information derived from the

natives was that the Konigsberg

had run short of coal, and that

her men had been felling palm

trees to obtain fuel. This

shortage of coal served to

explain why she had been lying

idle up the Rufigi River ever

since her exploit at Zanzibar a

month ago, when the old Pegasus

met her doom.

It

was one thing to discover the

Konigsberg, and quite another

thing to get at her. To start

with, there was a bar between

the open sea and the mouth of

the river, which the Chatham

could only cross at high water;

then there was a likelihood of

obstructions sunk in the river

channel, and of mines; and then

there was the certainty of

opposition from the shore on

either side of the river mouth,

for the Germans had been busy

digging trenches, rigging up

barbed wire, and making gun

emplacements, in which they had

mounted the guns of the

Konigsberg's secondary armament.

All these defences were well

concealed behind the palm trees

and thick undergrowth.

The

first thing the Senior Naval

Officer did was to inform by

wireless the Dartmouth and the

Weymouth, who were searching the

coast farther south, that their

quest was at an end, and that

they were to rejoin the Chatham.

He then set about sounding and

buoying a channel towards the

river mouth. By the river mouth

must be understood that passage

through the delta where the two

channels, called Simba Uranga

and Suninga, make their exit to

the sea. According to the

information gleaned from the

natives the other three channels

were impassable by large ships.

Meanwhile

the range was taken of the

Somali, which was lying a little

nearer than the Konigsberg. It

was found to be just over 14,000

yards, and so the Chatham opened

fire on her with 6-inch lyddite

shells. The effect of the fire

could not be ascertained, for

the Somali's hull was invisible

behind the palm trees, and even

her masts could only be seen by

the spotters at the mast-head.

One result of the bombardment,

however, soon declared itself.

The masts of the Konigsberg were

seen to move, slowly at first,

but as the ship gathered way,

they glided rapidly past the

tops of the palm trees. For a

moment there was a state of keen

anticipation on board the

Chatham, for they really thought

that the German cruiser was

coming out to engage them, and,

as Alexander Pope says, hope

springs eternal in the human

breast. But the Konigsberg had

no such intention; all she

wanted to do was to make sure of

being outside the Chatham's

range, so she slunk away another

six miles farther up the river,

and there dropped her anchor

again.

Was

she now safe from bombardment?

It must be remembered that the

Chatham was five or six miles

out to sea, but, supposing she

managed to cross the bar and to

reach the river's mouth, it was

just possible that she might

find the Konigsberg within her

range then. At all events it was

worth trying, and so the work of

buoying a channel continued

briskly. One morning, however, a

look-out from the mast-head

reported that the Konigsberg' s

masts had disappeared, and he

could see nothing of her

anywhere.

Here

was a startling mystery, but the

explanation of it was not hard

to guess, and the Chatham

carried on with her work. As

soon as the channel had been

buoyed and the spring tide came

round, she crept in gingerly,

passed over the bar, and

anchored about a mile and a half

from the entrance to the river.

And then the look-out in the

foretop was able to solve the

mystery of the sudden

disappearance of the

Konigsberg's masts. The

top-masts had been struck, and

in their place had been rigged

the tops of two cocoanut palms,

so that in the distance nothing

but these could be seen. It was

a better trick than painting a

white cross on a collier's hull,

and besides having the merit of

being a legitimate device of

warfare, it was worthy of any of

those animals who make a

practice of protective mimicry,

such as the arctic fox, who

changes his coat to white when

the snow comes, or the mantis,

who pretends he is a pink

flower.

The

Chatham opened fire at once, for

she had no time to lose if she

was to get back across the bar

with the ebb of the tide. Her

trouble was that the gunlayers

could see absolutely nothing of

their objective, and her

spotters found it almost

impossible to spot the fall of

the shells amidst the thick

vegetation of the delta. It

became very obvious that there

was very little chance of

settling accounts with the

German raider until some

aircraft arrived to help in the

operations. When the Chatham

recrossed the bar she had less

than a foot of water underneath

her, and her captain made up his

mind that he had had quite

enough of that experiment.

Meanwhile

the Dartmouth and the Weymouth

had arrived on the scene, and

had filled in their time with

frequent bombardments of the

trenches and barbed-wire

entanglements on either side of

the river entrance. The result

was that the trenches at the

extreme ends were evacuated by

the Germans, who came to the

conclusion that life in them had

too many crowded hours to it to

be comfortable. The Chatham

devoted her attentions to the

Somali, and though her fire was

indirect, and the spotting

extremely difficult, she

succeeded in plumping at least

one shell into the ship, and in

causing a fire to break out on

board.

The

next experiment was a scheme to

send in armed picket-boats,

carrying a couple of torpedoes,

to be fired at the Somali, but

it turned out a failure. The

boats were greeted with a heavy

fire from rifles and

machine-guns, which were so

effectually hidden in a mangrove

swamp on the south side of the

river that it was impossible to

locate them. An extraordinary

accident occurred to one of the

torpedoes, which no one was able

to explain. Possibly the

releasing gear was struck by a

bullet, or possibly a torpedo

man lost his nerve amidst the

rattle and clatter of the

enemy's shot; but, anyhow, the

torpedo was released

prematurely, and all it did was

to sink to the bottom without

either a run or an explosion.

The other torpedo was out of

gear, and so the experiment had

to be abandoned, and the boats

returned to their respective

ships, fortunately with nothing

more than very light casualties.

One

result of these experiments was

the decision that, since the

Konigsberg refused to come out

of her retreat, she had better

be locked up inside it. With

this object in view, a large

collier of venerable antiquity

was brought from Zanzibar and

preparations were made to take

her into the river, moor her

athwart the fairway, and then

sink her, so as to block the

channel. Iron plates were fixed

round the steering-wheel of her

forebridge to protect the

helmsman from rifle fire, and

her crew were taken out of her

and replaced by officers and men

of the Chatham. A flotilla of

steam-cutters and a picketboat

belonging to the three ships,

together with a vessel of light

draught, called the Duplex, were

to accompany the Newbridge,

covering her advance, as far as

possible, by their fire, and

assisting her in various other

ways. The picket-boat was to

carry a torpedo, which was to be

fired at the Newbridge, if other

methods of sinking her failed.

One of the steam-cutters was to

stand by to take off her crew

when she was abandoned. Another

steam-cutter was to land a party

on the left bank of the river,

to see what they could find

there. All the men were to wear

life-belts, and to carry their

rifles, and the steamboats and

the Duplex were to be armed with

maxims.

Before

daybreak on 7th November the

flotilla headed for the mouth of

the river, the Newbridge

leading, and arrived there at

half-past five in the morning.

All seemed quiet at first, and

not a soul was to be seen on

shore, but as soon as the

Newbridge turned round the bend,

the music of maxims and rifles

broke the silence, and the

bullets pattered like hailstones

against the iron plates which

protected her crew. But she kept

steadily on her course, entered

the Suninga Channel, and just

before six o'clock reached her

destination.

It

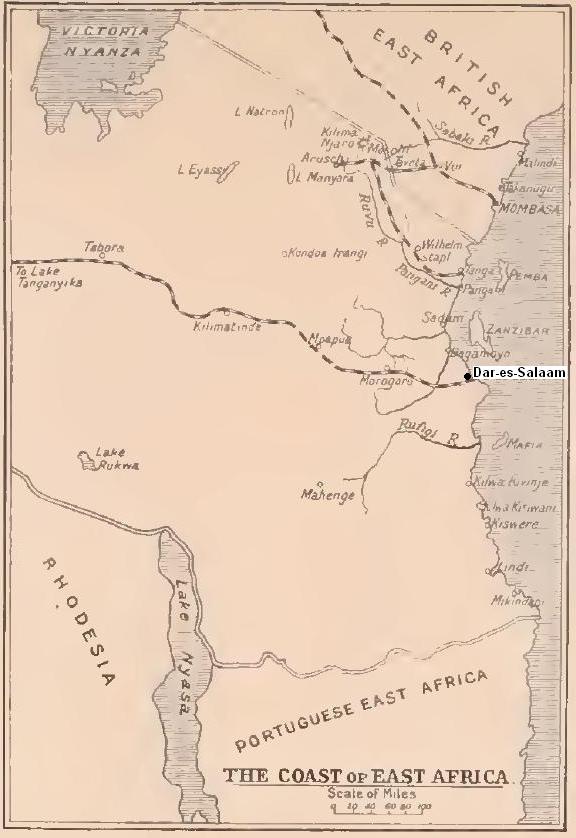

is not very obvious from the map

of the Rufigi Delta why the

Suninga Channel was selected to

be blocked. More direct access

to the sea is afforded by the

Simba Uranga Channel, and it was

in this channel that the

Konigsberg was lying when she

was first discovered. Since then

she had moved up above the point

where the two channels met, and

one might suppose that either of

them could be used by her. This,

however, was not the case,

according to the opinion of the

natives. They were unanimous in

the view that only the Suninga

Channel had water enough to

admit of the passage of a ship

of the Konigsberg's size, and

for the present we had to be

content to accept this view as

correct.

When

the Newbridge arrived at the

position marked C on the map,

she shut off her engines, and

proceeded to anchor bow and

stern. This was carried out to

the accompaniment of a ceaseless

patter of bullets, occasionally

varied by the dull thud of

something heavier striking her

sides and superstructure. The

enemy evidently had some small

guns commanding the spot, and

they were resolved to make

things as unpleasant as they

possibly could. To sink a vessel

in the exact position required

for blocking a channel is not so

easy as it sounds. The Turks

tried it many times up the

Tigris and Euphrates, and

invariably made a mess of it;

the Germans tried it on a large

scale to bar the approaches to

Duala, in the Cameroons, and

they, too, did the work very

badly, using up quite a large

number of ships before they

succeeded in making a barrage.

It is the kind of job which

cannot be done in a hurry, and

to do it under fire requires a

remarkably cool nerve. The

Germans knew this, no doubt, and

by pouring shot and shell into

the Newbridge they hoped to

spoil the operation.

This

hope, however, was doomed to

disappointment. As soon as the

ship was moored securely across

the channel, the main inlet

valve was opened, and she began

to settle by the stern. Her

commanding officer was fearful

at first lest the force of the

current should carry her stern

round, but the anchors held

firmly, and in a short time the

stern had grounded on the

bottom. The crew were ordered to

assemble near the port ladder,

and in spite of the heavy fire

directed at them, they fell in

as unconcernedly as though they

were in Sheerness Harbour and

the quartermaster had piped

“Both watches fall in for

exercise.” The steam-cutter,

which was waiting to take them

off, also came in for her share

of the enemy's fire, but it

failed to disconcert her crew.

The

last thing to do before

abandoning the ship was to place

an explosive charge in her, and

connect it to an electric

circuit, of which the ends were

carried into the steam-cutter,

and, as soon as they were at a

sufficient distance, the charge

was exploded and the ship,

listing to port, sank to the

bottom of the river, where she

lay very nearly at right angles

to the line of the channel. No

one could have made a neater job

of it.

Then

came the exciting business of

getting out of the river again.

The enemy's 3-pounders, rifles,

and machine-guns were busy all

the time, but our boats were

also armed, and replied as well

as they could, though the

Germans took good care to keep

themselves in hiding. The Duplex

was there to lend her support,

and did useful work in keeping

down the enemy's fire. But her

commanding officer, Lieutenant

Triggs, R.N.R., received a nasty

wound in the back of his

shoulder from a bursting shell.

The coxswain of one of the

steamboats and the leading

torpedo man in the picket-boat

were unfortunately killed, and

eight other men were wounded.

But considering the nature of

the work to be performed, our

casualties were remarkably

light.

So

the Suninga Channel was blocked,

and at the time we confidently

believed that the Konigsberg was

bottled up. But after a few days

the Kinfauns Castle arrived,

bringing a seaplane with her,

and the aerial reconnaissances

started. The officers of the

R.N.A.S. would seem to take a

positive delight in upsetting

everybody's preconceived

notions, and they found that the

Rufigi River gave them endless

scope for this pastime. First of

all they said that the Simba

Uranga was a beautiful channel,

such as would delight the heart

of the Konigsberg's navigator;

whereat the Senior Naval Officer

said, "Then we will block it,”

and began to make arrangements

to bring another old packet from

Zanzibar to be sunk as an

obstruction. Then the airmen

said that the Kikunja Channel,

although not so attractive to a

navigator as the Simba Uranga,

was sufficiently tempting to

induce a bold spirit to try his

luck there. Finally they said

they that did not believe that

the Suninga Channel was blocked

by the Newbridge, as there

seemed to be quite a lot of

space between the wreck and the

north bank. And then the Senior

Naval Officer decided that he

would sink no more vessels in

the Rufigi River, for he might

continue that game until he had

sunk the whole of Great

Britain's mercantile marine, and

even then the R.N.A.S. would not

be satisfied. He still had his

own private opinion that the

Konigsberg was securely bottled

up, but in view of these reports

of the airmen there was no

alternative but to keep watch

outside, until measures could be

taken to destroy the Konigsberg

in her lair. He knew that she

was short of coal, even if she

could negotiate the channel, but

in war-time the Navy must take

no risks, and so the Chatham,

the Fox, the Kinfauns Castle,

and the Weymouth by turns kept

guard over all the exits from

the Rufigi Delta.

The

Chatham spent Christmas Day upon

this wearisome job, and it was

only natural that her officers

should have felt that something

should be done to mark the

occasion. In those early days of

the war, before our stubborn

English minds had received an

adequate comprehension of the

German species, the practice of

fraternising was rife

everywhere, and the illustrated

papers of December 1914 contain

many touching little pictures of

Tommy and Fritz expressing their

brotherly love for each other.

It is not easy, however, to

fraternise with an enemy some

twelve miles away, when he

stoutly refuses to come any

nearer. The Chatham's officers

saw this difficulty, and so they

had a raft built, and on the

raft they placed the largest

lump of coal which could be

found in the bunkers, and on

this lump of coal they affixed a

message of Christmas greetings,

and then they let the raft float

up the river with the tide. The

message ran, “Wishing you a

merry Christmas. Get up steam

for fifteen knots, and Come

Out.” But neither the present

nor the invitation was even

acknowledged.

The

occupation of Mafia Island took

place early in January 1915. It

was a necessary preliminary to

the maintenance of a strict

blockade on the coast of German

East Africa. Several dhows,

which had been trading with the

enemy, were captured, and these

we armed and turned into patrol

vessels. Before long the German

forces were faced with the fact

that they must rely upon

internal resources for food and

stores, since the great ocean

highway was completely closed to

them.

CHAPTER

III

DESTRUCTION

OF THE "KONIGSBERG"

(click

map to enlarge)

On

7th November 1914 the Newbridge

was sunk in the Suninga Channel

of the Rufigi River, with a view

to botthng up the Konigsberg,

but shortly afterwards our

seaplanes reported that in their

opinion the German raider could

still find a passage out of the

river. Consequently a strict

guard was kept over all the

outlets, until such time as

means could be found of giving

the raider her quietus.

Six

months later two of our

monitors, the Severn and the

Mersey, arrived on the scene,

and under the directions of

Vice-Admiral King-Hall

preparations were made for the

attack. The Germans were still

strongly entrenched on either

side of the only channels which

were believed to be navigable,

and they had taken the guns of

the Konigsberg's secondary

armament to support their men in

the trenches. Both trenches and

guns were well hidden in the

mangrove swamps, forests of palm

trees, and thick undergrowth,

which fringe the banks of the

river, so that it was impossible

to say what was the strength of

the enemy's forces here. To land

in a mangrove swamp, and make a

frontal attack on hidden

trenches and guns, is bound to

be a costly operation at all

times, and was certainly to be

avoided if other means could be

found of getting at the

Konigsberg. The monitor seemed

to offer the best solution of

the problem, for its light

draught would enable it to

proceed by channels which were

impassable by the ordinary ship,

and its long-range guns would be

able to compete with the guns of

the Konigsberg with some degree

of equality. In fact, the guns

of the two monitors were of

larger calibre than those of the

Konigsberg, but the latter had

the advantage of better

facilities for spotting, and the

still greater advantage of

having the ranges of various

points along the river carefully

calculated.

The

spotting for the monitors could

only be carried out by aircraft,

for in that dense belt of

vegetation it was impossible

from their fighting tops to see

anything more than the

Konigsberg's masts, and even

these were invisible to the

gunlayers below. The hull of the

ship was never seen throughout

the operations by anyone except

the observers in the aeroplanes.

The enemy on the other hand had

no aircraft for spotting

purposes, but a very simple

device took the place of it.

They knew all the possible

positions from which we could

attack, and so they stationed

men in the tree-tops somewhere

in the vicinity of these

positions, and arranged a simple

code of signals. As will be seen

later on, it was some time

before we discovered this

device.

On

6th July 1915, about four

o'clock in the morning, the

Severn and the Mersey proceeded

to cross the bar, and by

half-past five they had entered

the Kikunga Channel of the

river. As will be seen from the

map, this is the northernmost

channel, which, according to

seaplane reconnaissances,

afforded a possible exit for the

Konigsberg, but according to the

opinions of the natives was not

navigable by any large craft.

The monitors were followed as

far as the entrance to the

channel by a variety of craft,

which came in to support them.

The Tweedmouth, a light draught

steamer, bore the flag of the

Commander-in-Chief; two small

whalers, the Echo and Fly, swept

ahead for mines, while the

Childers sounded to find the

channel; and the light cruisers

Weymouth and Pyramus also

crossed the bar.

The

Weymouth then proceeded to

bombard a position on the delta

known as Pemba, where we were

informed that the enemy had a

spotting station. It meant

long-range firing, without the

satisfaction of knowing the

result, for there was no

aircraft spotting for the

Weymouth. It seems fairly

certain, however, that the

German observation station at

Pemba, assuming that it existed,

was of very little service to

them. More important work for

the Weymouth was that of keeping

down the fire of the enemy's

anti-aircraft guns, for it was

essential that our aeroplanes

should be as free as possible

from interruption in their work.

It is at all times

unsatisfactory to fire at an

invisible target in the thick of

a forest, but there is no doubt

that the Weymouth succeeded in

planting shells near enough to

the antiaircraft guns to

restrict their activities within

reasonable limits.

It

must be remembered that the

Konigsberg was defended by a

good deal more than her own

guns, that military forces and

military guns of unknown

strength were hidden in the

thick vegetation, and that the

destruction of a ship, situated

as she was behind an

impenetrable delta, was no

ordinary naval operation. The

operation would, in fact, have

been almost an impossibility had

it not been for the assistance

of the aeroplanes. The aerodrome

was on Mafia Island, some thirty

miles from where the Konigsberg

was lying, and as there were

only two aeroplanes available,

and they necessarily had to

relieve each other from time to

time, there were some wearisome

pauses in the proceedings.

Flight

Lieutenant Watkins started off

at half-past five from the

aerodrome, carrying six bombs,

which he dropped as near as he

could to the Konigsberg, to keep

her attention occupied while the

Severn and the Mersey were

getting into position. The two

monitors on their way up the

river had been liberally fired

on by pom-poms and 3-pounders,

but this had not worried them

much, and by half-past six in

the morning they were anchored

head and stern at their allotted

stations. By this time the

second aeroplane had arrived,

with Flight Commander Cull as

pilot, and Flight Sub-Lieutenant

Arnold as observer, and the

monitors opened fire.

Let

no one imagine that spotting

from an aeroplane is a simple

job. It is hard enough for a

stationary observer to declare

with any degree of accuracy the

number of yards by which a shot

falls beyond or short of its

objective, but when the observer

is moving through the air at a

speed of eighty miles an hour or

more, the problem is rendered a

good deal harder, and when

shells from anti-aircraft guns

are popping all round him like

champagne corks at a banquet, he

is apt to be distracted by the

thought of such pleasant

associations. The aeroplane

observers over the Rufigi Delta

had other little troubles all

their own. The climate was

responsible for the worst of

these, for the effect of a cool

monsoon wind blowing over a

surface of land heated by a

tropical sun is very startling

at times. A “bump“ of 250 feet

is not uncommon, and I suppose

the scientific explanation is

that a stratum of warm air rises

rapidly through the cold air,

and when the aeroplane strikes

it the diminished density has

much the same effect as

releasing the catch on a winch

with a heavy weight at the end

of the hawser. Another trouble

was the thickness of the palm

forests surrounding the

Konigsberg. In these the

monitors' shells fell to explode

unseen, like flowers wasting

their sweetness on the desert

air.

On

6th July the two aeroplanes

between them covered a distance

of 950 miles. The first one

broke down soon after midday,

and the other one followed suit

about half-past three in the

afternoon, whereat it became

useless to continue the

operations, and the two monitors

had to withdraw from the river.

Their

experiences had not been by any

means devoid of excitement. The

Severn had no sooner reached the

river entrance in the early

morning than she saw two men

seated in the boughs of a tree

overhanging the water's edge.

Beneath them was a log, and

alongside the log was a torpedo.

Three rounds of lyddite promptly

fired from one of her guns left

nothing recognisable of either

the torpedo or the log, and the

two men disappeared completely.

When she got into her position

up the river, the Konigsberg

opened fired on her with four

and sometimes five guns, and the

firing was marvellously accurate

for range, but slightly out for

direction. This was a fairly

clear indication that the

Konigsberg's gunnery lieutenant

had been carefully calculating

the ranges of certain points on

the river. Presently the Mersey

was hit twice, one shell

striking the gun-shield of one

of her big guns on the port

side, and killing four men,

while part of the burst shell

went through a bulkhead into the

sick bay, and wounded the sick

berth steward. The other shot

struck a motor-boat lying on the

port side, and sank it, but did

no further damage beyond making

a dent in the ship's bottom. It

was a piece of luck that the

motor-boat was there, or the

Mersey would undoubtedly have

had a big hole below her

water-line.

After

this she retired, and had only

just left her anchorage when

another salvo fell upon the

exact spot. She anchored 500

yards lower down-stream, where

she found the atmosphere rather

more healthy. The Severn then

received the enemy's attention,

and later on, after a long pause

occasioned by the absence of our

aeroplanes. Captain Fullerton

came to the conclusion that it

would be wise to try a change of

billet. As the stern of his ship

swung round three lyddite shells

fell together on the position he

had just vacated, showing beyond

doubt that the enemy had both

range and direction to a nicety.

It

was just about this time that

somebody in the Severn spied a

party of four men up a tree.

Here was a complete explanation

of the Konigsberg's accurate

firing, and it showed that she

had a very shrewd idea as to

where the monitors would come to

make their attack. A few shots

from a 3-pounder gun brought

those four down with a run, and

after that the Konigsberg's

firing was far from accurate.

Captain Fullerton, however,

suspected the presence of

another observation post at

Pemba, and was careful to keep

well in to the west bank, so

that the hull of his ship could

not be seen from that direction.

Soon afterwards the second of

our aeroplanes broke down, and a

withdrawal from the river became

necessary.

The

result of the day's proceedings

was not altogether satisfactory.

According to the aeroplane

observers, four hits were

recorded on the Konigsberg, but

it was quite evident that a

further attack would have to be

made in order to complete her

destruction. It was not by any

means a pleasant occupation to

take ships up that shallow

channel, with every possibility

of running aground at any

moment, and with unseen field

and naval guns firing

continually from the recesses of

the forest to supplement the

shells coming from the

Konigsberg. The Mersey already

had four men killed and four

wounded (of whom two

subsequently died of their

wounds), and one of her port

guns had been put out of action.

The Severn was more fortunate,

having neither casualties nor

damage to report. But the day's

experiences were enough to show

that the task undertaken was far

from being a light one.

Five

days later, on 11th July, the

aeroplanes were again ready for

service, and the two monitors

crossed from Mafia Island and

entered the Kikunga Channel

shortly before noon. Their

progress up the river was

heralded by a chorus of

field-guns, machineguns, and

rifles, mostly from the east

bank, and the Mersey had three

men wounded by a 9-pounder

shell. But our return shot,

crashing blindly through the

thicket in the direction of the

sound of the hostile guns, soon

had the effect of quieting them.

Shortly afterwards the

Konigsberg opened fire with four

guns, concentrating her fire on

the Severn. This was

inconvenient, because the

arrangement was that the Severn

should get into position first,

and the operation of anchoring

bow and stern is not an easy one

under fire. So the Mersey

remained in the open to attract

the Konigsberg's gunners, and in

a very short time the Severn was

in position 1,000 yards nearer

the enemy than she had been

before, and comfortably steady

between her anchors. A sharp

look-out was kept for spotting

parties in the tree-tops, but

apparently they had come to the

conclusion that it might be too

warm up there to be healthy.

None

the less the Konigsberg's fire

was uncomfortably accurate. The

splash of her shells flooded the

quarter-deck more than once, but

fortunately no damage was done.

About half-past twelve one of

the aeroplanes came on the scene

with Flight Commander Cull and

Flight Sub-Lieutenant Arnold,

and the Severn opened fire. The

first five salvoes were lost in

the thick forest of palm trees,

and the aeroplane could give no

account of them. But the officer

in command of the Severn's guns

took upon himself to make a big

reduction in the range, which

turned out to be a fortunate

guess. The sixth salvo was

signalled by the aeroplane to be

100 yards over and to the right.

The necessary adjustment was

made, and the gun fired again.

This time the aeroplane

signalled too much to the left.

Again the direction was

adjusted, and another round

fired. All eyes were impatiently

watching the aeroplane to learn

the verdict. As it gracefully

swooped round in its circle

Sub-Lieutenant Arnold signalled

the joyful message - a hit! The

Severn's guns were all adjusted

to the ascertained range and

direction, and for the next few

minutes Arnold was kept busy

making the same signal.

Occasionally, however, he had to

record a short, or an over, or a

left, or a right, but the

finding of the range had been

accomplished, and the hours of

the Konisgberg were numbered.

In

the Severn they were all so much

engrossed in their task, which

had now for the first time

promised a successful issue,

that they had no time to notice

any peculiarity in the movements

of their friends in the sky. The

aeroplane had been at an

approximate height of 3,200

feet, but just as the first of

the Severn's shells had been

spotted, a lucky shot from the

anti-aircraft guns burst beneath

them, and a piece of it hit

their engine. There was no room

for doubt about it, for the

behaviour of the engine afforded

ample evidence, and in ten

minutes Flight Commander Cull

found that he had descended to

2,000 feet. The situation became

decidedly ticklish, for at that

height a direct hit by a shell

was well within the range of

possibilities, and the chances

of coming out of the ordeal

alive would be remote, to say

the least of it. But Commander

Cull realised that the crucial

moment had come, and that to

leave the scene just when the

Severn was getting on to her

target might very well ruin the

chances of the whole

undertaking. So he set his

teeth, and determined to hang on

as long as ever he could.

Then

Sub-Lieutenant Arnold signalled

the first hit, and the

excitement grew as the hits

became fast and furious. But all

the time the anti-aircraft

shells were bursting round them,

and presently another fragment

struck the aeroplane's engine.

Nothing remained now but to

volplane down as best they

could, so they made a signal to

the Severn, “We are hit; send

boat for us,” and Commander Cull

steered with a view to landing

in the river somewhere near the

two monitors. During the descent

Sub-Lieutenant Arnold continued

to send his spotting

corrections, until the machine

dipped below the tree-tops and

the Konigsberg was lost to view.

The observer's last signal to

the Severn was to bring her

salvoes farther aft, and he had

the satisfaction of seeing her

shells fall into the Konigsberg

amidships before the palm trees

obscured his view. By that time

nine salvoes had been signalled

as having hit the enemy.

The

aeroplane fell into the river

not far from the Mersey, who

promptly sent a boat to the

rescue. Sub-Lieutenant Arnold

was thrown clear of the machine

into the water, but Commander

Cull was strapped to his seat,

and was in an awkward

predicament, as the machine

turned right over. But Arnold

went to his assistance at once,

and managed to extricate him;

within a few minutes both of

them were safely in the Mersey's

boat. The wreck of the aeroplane

was blown up by gun cotton, as a

precaution against its falling

into the hands of the enemy.

By

this time two of the

Konigsberg's guns had ceased

fire; a few minutes later only

one of the guns was firing, and

after another minute or two

there was silence. But the

silence did not last long, for

almost immediately a loud

explosion was heard, and dense

clouds of smoke rose up above

the palm trees, and drifted away

in the wind. The Severn still

continued firing with two of her

guns, and soon there were no

less than seven distinct

explosions heard, and the yellow

smoke made a big cloud over the

tops of the trees.

The

monitors were then ordered to

proceed upstream and close to

within 7,000 yards of the enemy.

The navigation was no easy

matter, as there appeared to be

a bar right across the river,

but they crept up gradually, and

when the soundings showed eight

feet of water, the Mersey put

her helm over and dropped

anchor. By this time the other

aeroplane had arrived with

Flight Lieutenant Watkins and

Flight Sub-Lieutenant Bishop,

and with her third round the

Mersey scored a hit. The

Konigsberg was now visible from

the topmast heads of the

monitors, in their new position,

and Captain Fullerton himself

went aloft to reconnoitre. He

saw that the enemy was on fire

both fore and aft, that her

foremast was leaning over and

looked on the verge of collapse,

and that streams of smoke

enveloped her mainmast. In fact

she was a complete wreck, and at

half-past two in the afternoon

the Admiral, satisfied that the

difficult task at last had been

accomplished, signalled to the

monitors to retire.

Captain

Fullerton of the Severn,

Commander Wilson of the Mersey,

Squadron Commander Gordon in

charge of R.N.A.S. detachment,

Wing Commander Cull, and Flight

Lieutenant Arnold were all

awarded the Distinguished

Service Order for their

respective shares in this

achievement. It was a task which

in many of its features was

unique in the annals of the

Navy. Certainly no naval

engagement has ever before been

fought under circumstances even

remotely similar, for it may be

described as a naval battle in

the midst of a forest. It is

equally certain that the new

branch of the Navy, the Royal

Naval Air Service, had never

before been called upon to carry

out such important work under

such climatic conditions.

Perhaps only flying men can

appreciate how difficult those

conditions were, but the story

of those exciting minutes

when, with damaged engine, the

spotters were guiding the

Severn's shots nearer and nearer

to the target, is dramatic

enough to appeal to the

imagination even of the most

prosaic among laymen.

CHAPTER

IV

AN

AIRMAN'S ADVENTURES

(click

map to enlarge)

At

Chukwani, in the island of

Zanzibar, Squadron No. 8 of the

Royal Naval Air Service

established its headquarters for

the purpose of making

reconnaissances over enemy

territory in East Africa, taking

photographs, dropping bombs, and

otherwise aiding the military

operations. The seaplane

carriers, H.M.S. Himalaya and

Manica were lying off the

island, and the Flag Commander,

the Hon. R. O. B. Bridgeman,

D.S.O., had general charge of

the operations. Although he was

not an airman himself, he was

keenly interested in the

airman's craft, and moreover he

fully appreciated the special

difficulties attending aviation

in that climate. The R.N.A.S.

had every reason to be grateful

to him, for he helped them in

their work as only an officer

with a sympathetic understanding

of their troubles could help

them.

In

January 1917 the Manica and

Himalaya were lying off the

island of Nyroro near the Rufigi

Delta, and on the 5th of the

month the former ship sent

Flight Sub-Lieutenant Deans over

the delta in a seaplane. On his

return journey, when he was just

over the wreck of the Konigsberg

and was circling round to get a

photograph of a pinnace in her

vicinity, he was fired at by

rifles, one shot hitting his

port wing. He was fired at again

lower down the delta, but

suffered no further damage, and

returned in safety. His machine

had refused to ascend with an

observer on board, and he had

therefore made the flight alone.

Since

the Manica's seaplane was

temporarily incapable of

carrying both pilot and

observer, it was decided next

day to send up the Himalaya's

machine, piloted by Flight

Commander E. R. Moon, and with

Commander Bridgeman himself as

observer. Soon after seven

o'clock in the morning they

started off, taking with them a

camera and enough petrol to last

for three hours, and they flew

over the delta with the

intention of making a thorough

reconnaissance of it. As the

hours slipped by, and there was

no sign of them, their shipmates

began to grow anxious, and, when

anxiety had given place to

alarm. Flight Sub-Lieutenant

Deans was sent off from the

Manica to discover what had

happened to them.

He

searched up and down the various

channels and creeks, but at

first could see no trace of

them. On his return, just as he

was passing over the Suninga

Channel, he noticed something

lying on the water at a spot

which he estimated to be about

six miles from the mouth of the

channel, and on descending

towards it, he found it to be

the wreck of the missing

seaplane. He came down close

beside it, and saw that it was

lying upside down with the

bottom of the floats just above

water, and that large portions

of the wings, tail, and rudder