|

|

Admiral

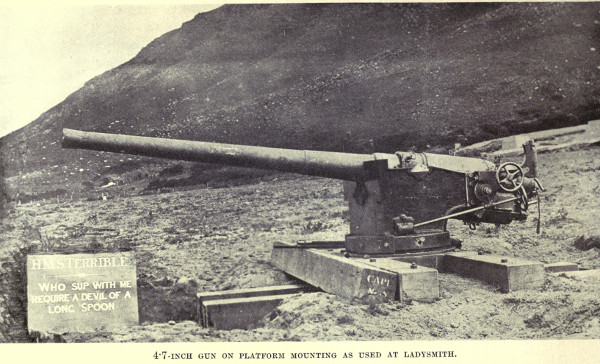

Sir Percy Scott, 4.7in gun as used at Ladysmith (click

to enlarge) |

return to "Pax Britannica", 1815-1914 |

|

A Modern Introduction

Admiral

Scott's memoirs are a valuable introduction to the Navy

in the second half of the Victorian era and to the

development of modern gunnery. I have heard him

described as the father of gunnery, and see nothing in

this book to contradict that. His scientific

investigations and technological solutions were

impressive, and his leadership and seamanship skills

equally so.

Any

transcription and proofing errors are mine.

Gordon Smith, Naval-History.Net |

FIFTY YEARS IN THE ROYAL NAVY

by

ADMIRAL

SIR PERCY SCOTT, BT., K.C.B., K.C.V.O., HON. LL.D. CAM

With Illustrations London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, W 1919 Images of some of the ship he served on have been added for the reader's information |

Entry into the Navy - Life in the Britannia - My First Seagoing Ship - A Sailing Passage to Bombay - Discipline on Board - Chasing Slave Dhows - The Slave Market at Zanzibar - Lessons in Seamanship - Gazetted Sub-Lieutenant - With H.M.S. Active on the West Coast of Africa - Life on Ascension Island - A Punitive Expedition up the Congo - A Successful Operation - More River Expeditions - On Board the Guardship at Cowes - An Incident of the Crimea, page 1

Admiralty Attitude towards Gunnery - Uselessness of Inspection - A Typical Report of the Period - Course of Instruction on board H.M.S. Excellent - Mud Island - Convict Labour - A Scheme of Drainage - Gunnery Lieutenant of H.M.S. Inconstant - A Training Squadron - Masts and Sails - The Young Princes as Midshipmen - The Boer War takes us to the Cape - Voyage to Australia - Parting with the Bacchante - Invention of an Electrical Range Transmitter - How the Admiralty regarded it - Back in Simon's Bay - A Fire on Board - Putting out the Flames in a Diver's Dress 25

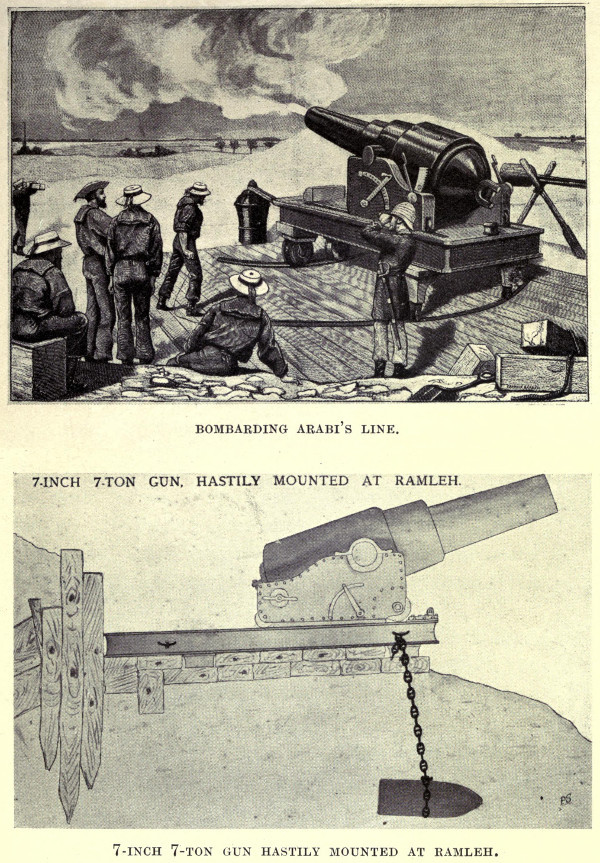

Ordered to Alexandria - Naval Brigade Ashore - Collecting Unexploded Shell - Fleet's Deplorable Shooting - Improvisation - Mounting 7-ton Guns - Blowing up a Dam - Queen Victoria and her Troops - Bluejackets and their Medals, 46

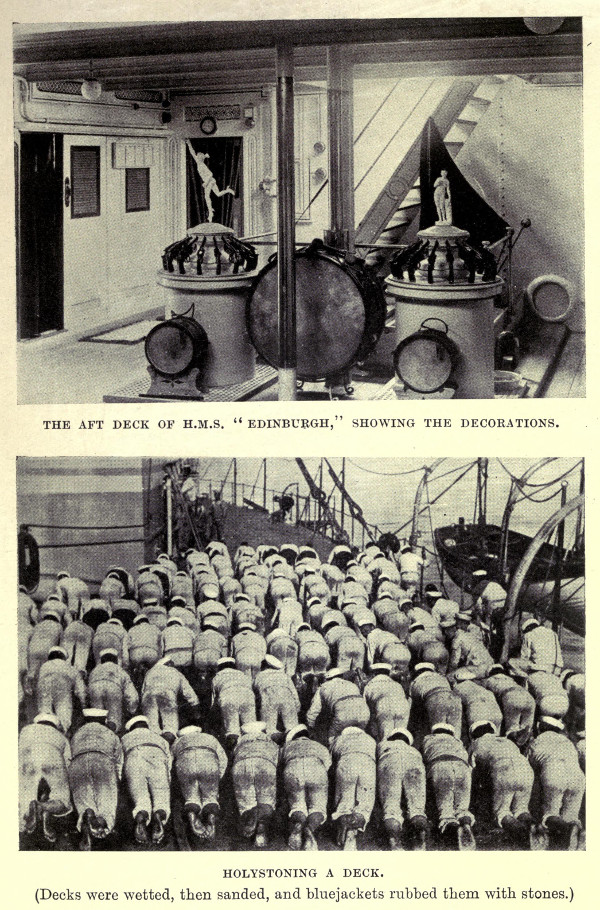

H.M.S. Excellent again - King George's Gunnery Course - Improvements in Big Gun Targets - Service on board H.M.S. Duke of Edinburgh - Making Ships look Pretty - Duke of Edinburgh's Interest in Gunnery - Invention of a Signalling Lamp - How the Admiralty treated it - Sinking of H.M.S. Sultan - A Unique Salvage Operation - Back to Whale Island - A Prophecy fulfilled - How a Cricket Pitch converted the Admiralty - Convict Labour - A Committee on Naval Uniform - A Naval Barnum - How the Royal Naval Fund was instituted - Farewell to Whale Island, 58

In the Mediterranean again - Condition of Gunnery and Signalling - Revolutionising Night Signalling - The Admiralty and Inventions - A Source of Discouragement - The Boat that went Adrift - The Scylla's Cruise - Improvement in Gunnery - A New Sub-calibre Gun and Target - History of the "Dotter" - Prize Firing - The Scylla's Triumph - On Half-pay, 73

In Command of H.M.S. Terrible - State of the Ship's Gunnery - Useless Appliances - Making Good Defects - Arrival at the Cape - The South African War - Deficiency in Long-range Guns - Mounting Naval Guns for Service Ashore - Why the 4.7-inch Guns were sent to Ladysmith - Admiral Sir Robert Harris's Statements - A Recital of the Facts - How the Mountings were turned out - The Value of the 12-pounders - Appointment as Military Commandant of Durban - Prince Christian Victor of Schleswig-Holstein - A Keen Soldier - Assistance in the Defence of Durban - General Buller's Visit - The Man-hauled 4.7-inch Gun - An Effective Object Lesson - Communication with Ladysmith - Mounting the Terrible's Searchlight on Shore - Successful Signalling, 90

Military Commandant of Durban - Multifarious Duties - Censorship: an Effective Threat - The Spy Trouble -A Boer Agent's Claim for Damages - Contraband Difficulties - The Bundesrath - Guns for General Buller - A Gun-Mounting in Fifty-six Hours - Hospital Ships - Mr. Winston Churchill - Relief of Ladysmith - A Letter from Sir Bedvers Buller - Farewell to Durban, 113

H.M.S. Terrible's Welcome in the East - Hong Kong's Lavish Hospitality - News of the Boxer Outbreak - Orders at last! - Arrival at Taku - Tientsin's Plight - The Relief Column - Long-range Guns left behind - A Neglected Base - Anomalies of the Situation - Useless Appeal to the Admiral - Belated Use of the Rejected Guns - Capture of Tientsin - Relief of the Legations, 128

A Return to Gunnery at Sea - Results of the First Prize Firing - A Machine to increase Efficiency in Loading - The Deflection Teacher and its Effect on Shooting - Re-modelling the Target - Target Practice of the Fleet - Underlining an Inference - Admirals and Prize Firing - Back at Hong Kong - Raising the Dredger Canton River - Lieut. Sims, U.S.A., and Gunnery - Sir Edward Seymour's Valuable Reforms - Admiralty Opposition - Prize Firing of 1901 - First Ship of the Navy - The Barfleur and the Terrible's Example - The Admiralty and Improved Shooting - A Disastrous Order, 138

Wei-hai-wei Controversy - Naval Base or Seaside Resort? - Wei-hai-wei's Useless Forts - A Report to the Admiralty - Further Work stopped - Final Prize Firing - Petty Officer Grounds' Record - The Homeward Voyage - A Congratulatory Address - Reception at Portsmouth - Visit to Balmoral - The King's Deer Drive - How I shot a Hind - His Majesty's Interest in Naval Gunnery, 164

Efforts towards Reform - Admiralty Obstruction - Waste of Ammunition - Official Reprimands - Two Gunnery Committees appointed - Conflicting Reports - The Centurion's Gun Sights - A Tardy Discovery - The Dawn of a New Era, 178

My Appointment as Inspector of Target Practice - Battle Practice Conditions - Order out of Chaos - Improvement at Last - My Visit to Kiel - The Chief Defect of the German Navy - A Lost Experiment - "Director Firing", 189

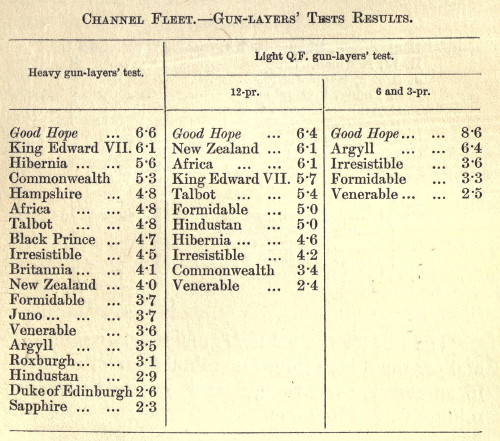

In Command of the Second Cruiser Squadron - Obsolete Ideas - Inadequate Training for War - Housemaiding the Ship Paramount - The Test of War - Confusion and Unreadiness - Wrong Pattern Torpedo - Lord Charles Beresford and the Admiralty - H.M.S. Good Hope's Gunnery - First in the whole Fleet - Our Cruise in Northern Waters - My New Appointment - An Independent Command - A New Routine and Efficiency, 198

En route to the Cape - Durban's Welcome - The National Convention - Old Foes and New Friends - An Inland Trip - At Pretoria and Johannesburg - Lavish Hospitality - Farewell to Durban - Festivities at Capetown - Farewell Messages - Off to the New World - Arrival at Rio - Promoted ViceAdmiral - Brazilian Enthusiasm - The President's Visit to the Good Hope - Uruguay and the Navy - Speeches at Montevideo - The Pelorus at Buenos Ayres - A Great Modern City - Departure from Montevideo - Battle Practice at Tetuan - I haul down my Flag, 214

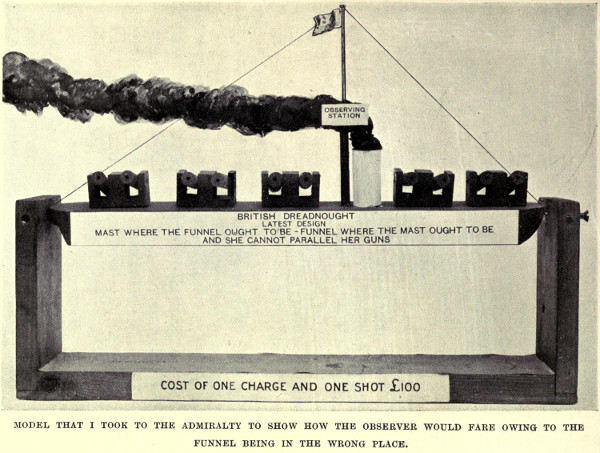

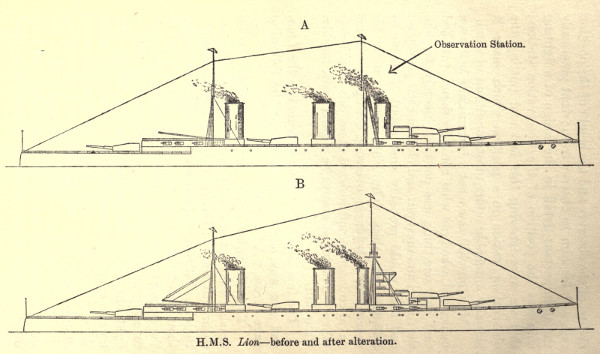

My New System of Routine - Approved by Lord Fisher but generally Opposed - What Naval Gunnery means - No further Employment at Sea - Back to Director Firing - Success of the Neptune Trials - The Thunderer and Orion Test - Superiority of Director Firing demonstrated - More Admiralty Delay and a Stiff Protest - Warning unheeded and Proposals rejected - Tragic Fruits of Neglect - History of Parallel Firing - Position of Director Firing at the Outbreak of War - The First Dreadnought - Position of the Mast - Perpetuating a Blunder - Mr. Churchill's Wise Decision - A New Blunder in Exchange for the First, 241

A Letter from Prince Henry of Prussia - Created a Baronet and promoted to Admiral - Menace of the Submarine - Protective Measures necessary - The Official Attitude - Lessons of Manoeuvres - The Admiralty unconvinced - Mr. Winston Churchill's Suggestion - Director Firing - My Services dispensed with - A Remarkable Letter from Whitehall, 268

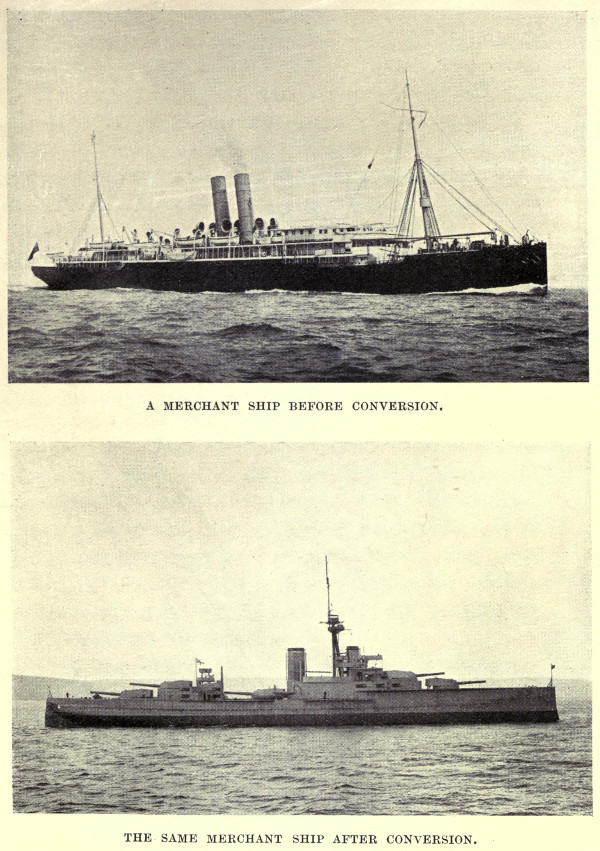

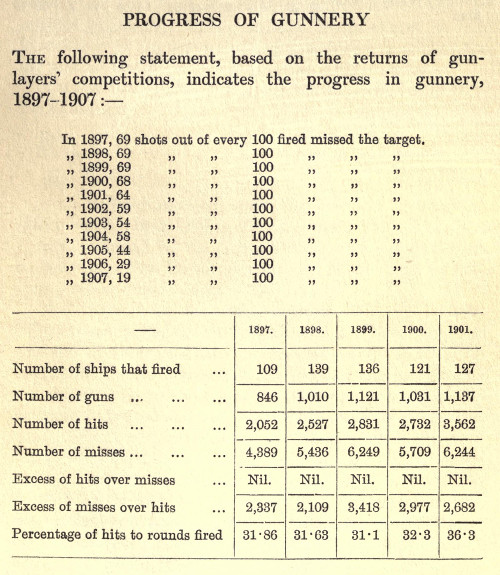

The Shadow of Ireland - Letter to the Times on Submarines - Criticisms by many Naval Officers - The War settles the Controversy - The War Office and the Lack of Big Guns - Lord Roberts' Advice ignored - Ten Months' Delay and Repentance - The Fleet's Gun Equipment - Recall to the Admiralty - Fitting out the Dummy Fleet - The Submarine Problem demands Attention - Visit to the Grand Fleet - The Peril of the Grand Fleet - Lord Fisher's Influence - The Tragedy of the Battle of Jutland - Official Persistence in Error - The Dardanelles Failure - Gunnery Practice in the "Sixties" - Successive Changes in the Target - Valueless Prize Firing - My Suggestions for Improvement - Method adopted on the China Station and its Results - Admiralty Opposition to its Adoption - King Edward's interest in the Question - Admiralty insist on a New Rule with Disastrous Effects - Immediate Improvement, 273

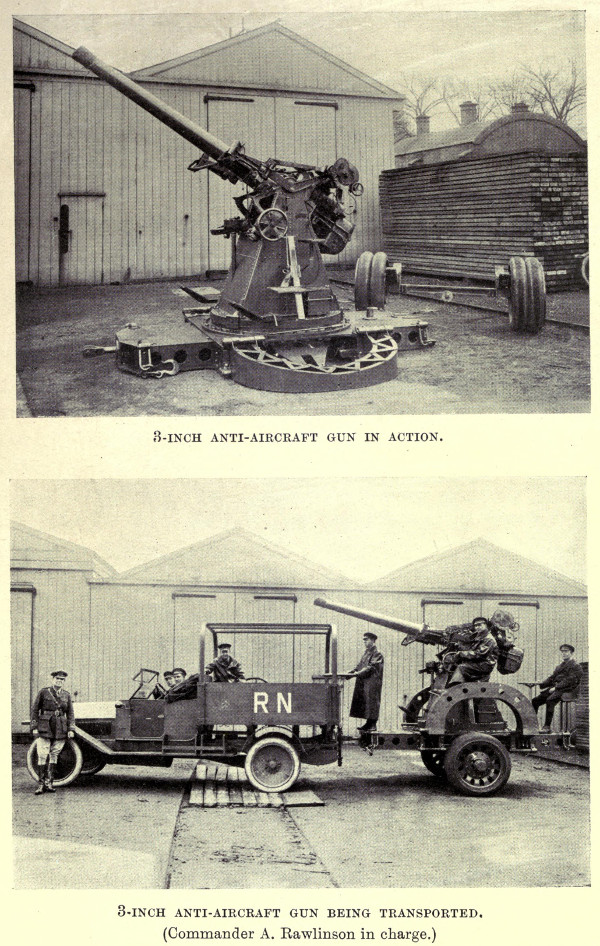

A Providential Raid by a Zeppelin - London Undefended - My Recall to the Admiralty - Deficiency of Guns - Unsuitable Ammunition - Commander Rawlinson's Good Work - A Flying Visit to Paris - Co-operation of the French - My Protest against Admiralty Methods - Termination of my Command - The Anti-Aircraft Corps - Target Practice in the Air, 303

Guns for the Army - Visit to the Front - Inferior Elevation of the 9.2-inch Gun - The Mounting improved after Official Delay - Naval Searchlights - A Primitive Method - My Improved Design - A New System ultimately adopted - A Letter from the Admiralty - The Dardanelles Commission - A Question of Gunnery - The Essence of the Problem - A Criticism of the Report, 321

APPENDIX II 337

(not included)

Smoke Dresses 44

Bombarding Arabi's Line 52

7-inch 7-ton Gun Hastily Mounted at Ramleh 52

The After-Deck of H.M.S. "Edinburgh,"Showing the Decorations 60

Holystoning a Deck 60

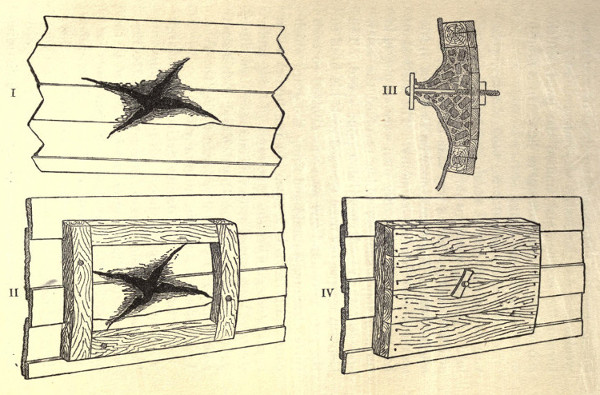

Mending a Shot-Hole in H.M.S. "Sultan" 65

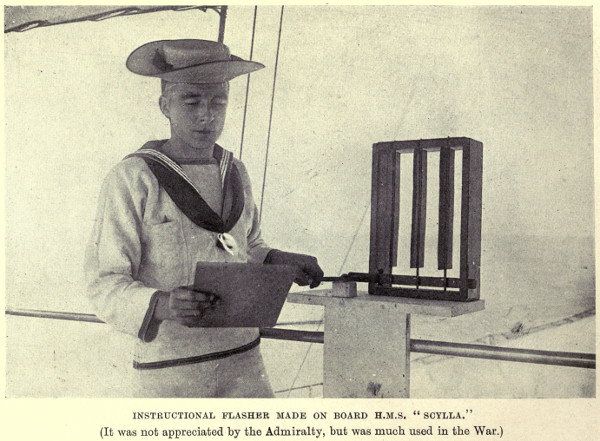

Instructional Flasher made on Board H.M.S. "Scylla" 75

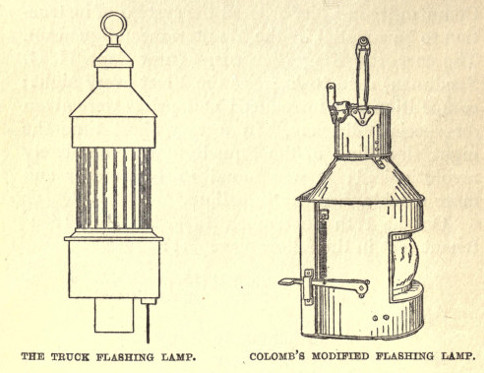

Flashing Lamps 76

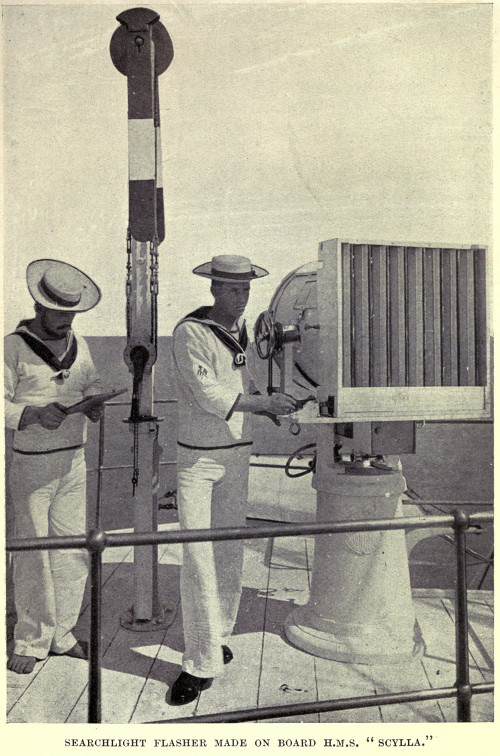

Searchlight Flasher made on Board H.M.S. "Scylla" 76

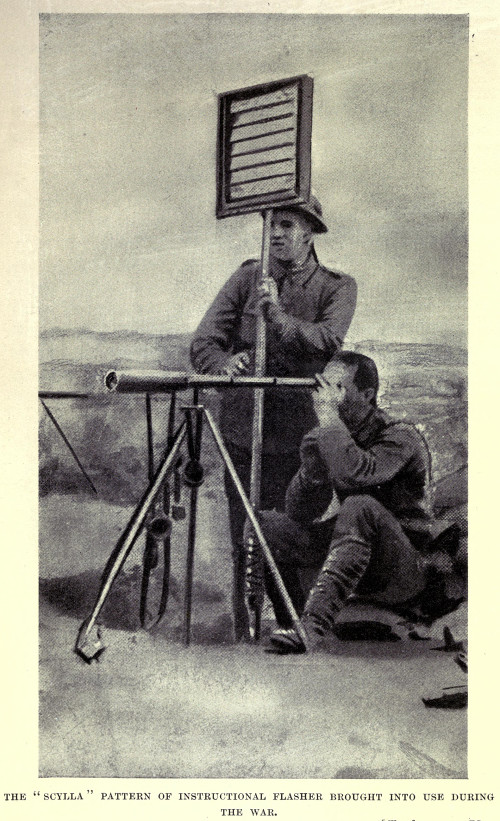

The "Scylla" Pattern of Flasher Brought into use During the War 78

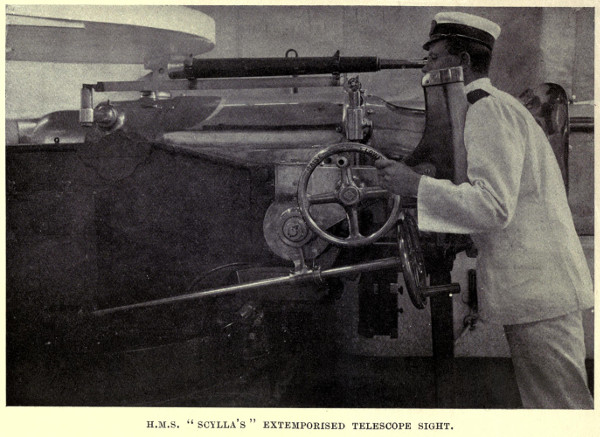

H.M.S. "Scylla's" Extemporised Telescope Sight 82

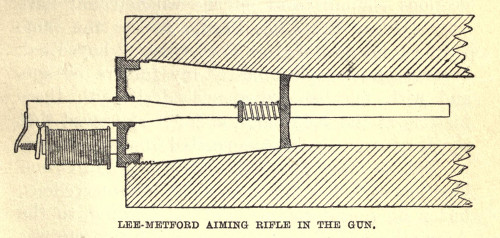

Lee-Metford Aiming Rifle in the Gun 83

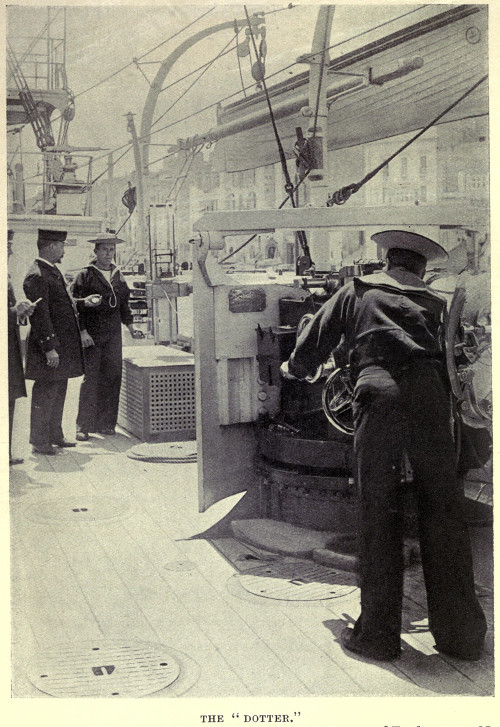

The "Dotter" 88

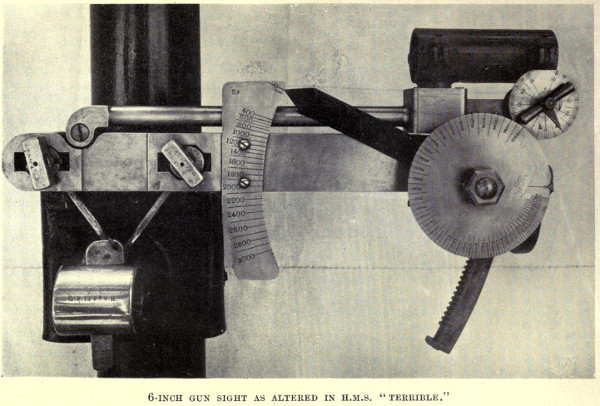

6-inch Gun Sight as altered in H.M.S. "Terrible" 92

4.7-Inch Gun on Platform Mounting as used at Ladysmith 98

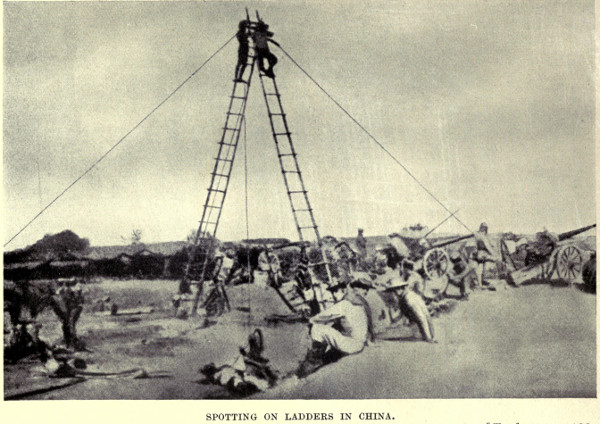

Spotting on Ladders in China 136

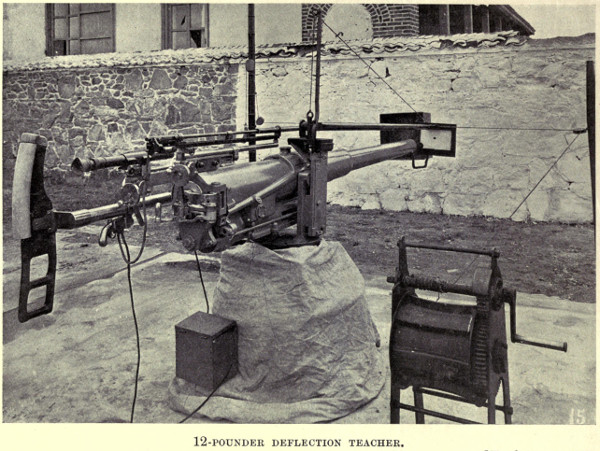

12-Pounder Deflection Teacher 140

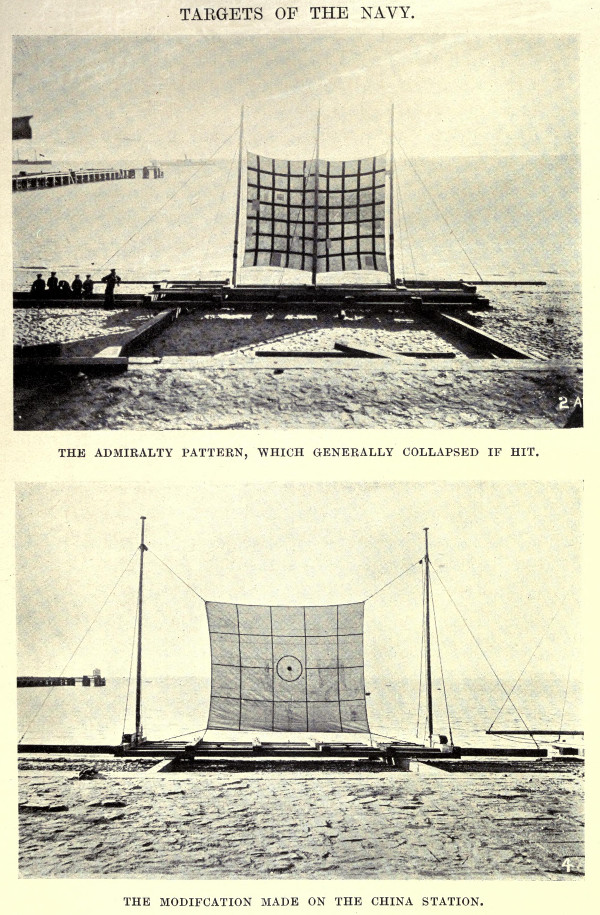

Targets of the Navy 142

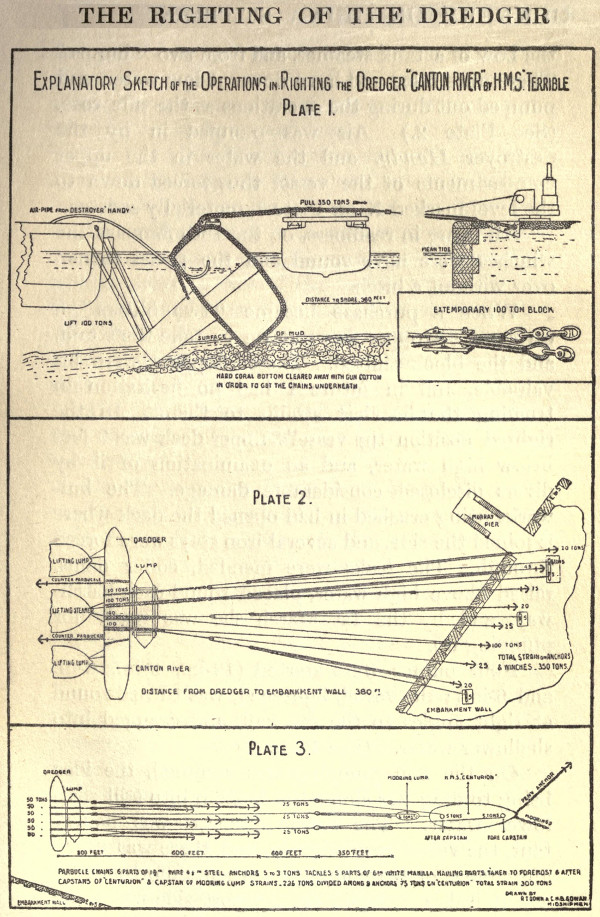

Operations in Righting the Dredger 147

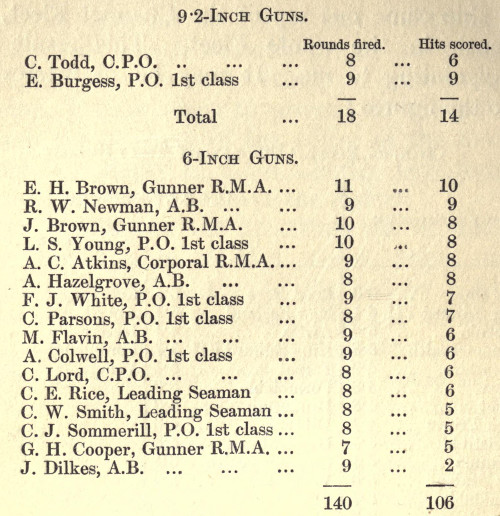

"Record Performances" 176

My Son entering Portsmouth Dockyard, where, as Captain of the "Excellent,"I had a residence 178

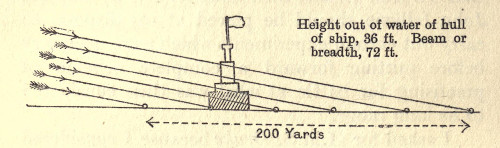

The Spread of Shot 180

My Motor-Car, changed into an Armoured Car, as used during a Sham Fight, on 24th Feb., 1904 186

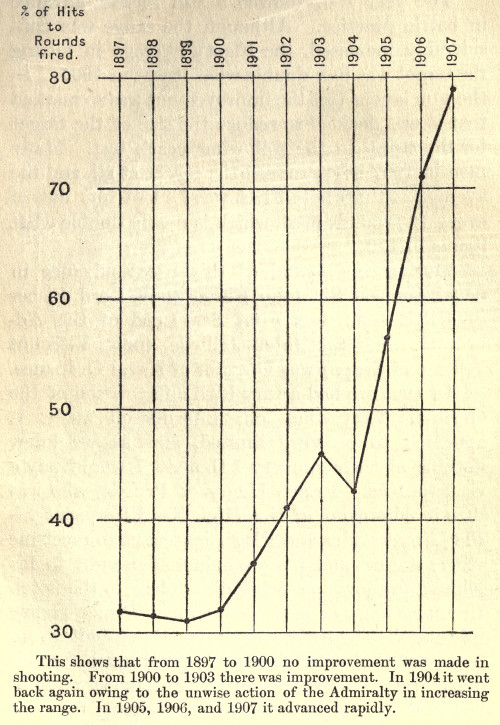

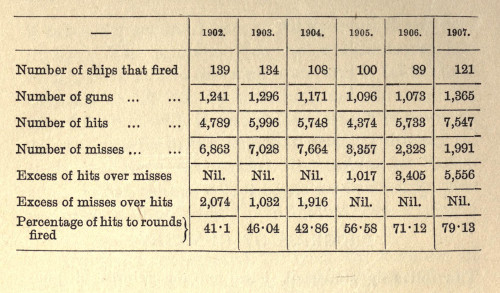

Chart of Hits to Rounds Fired 193

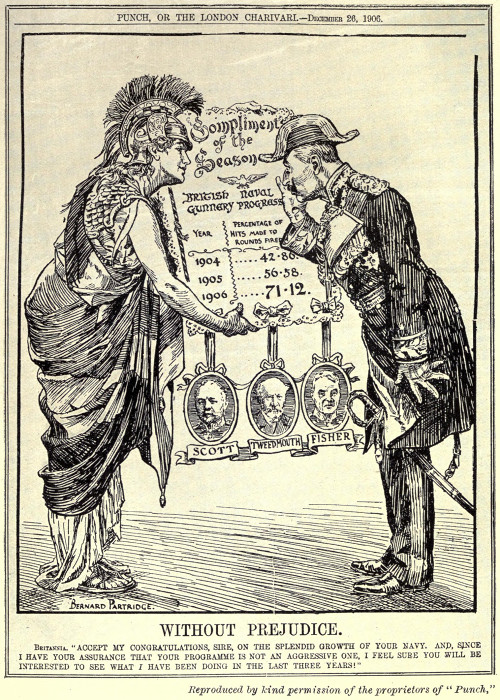

"Without Prejudice" 194

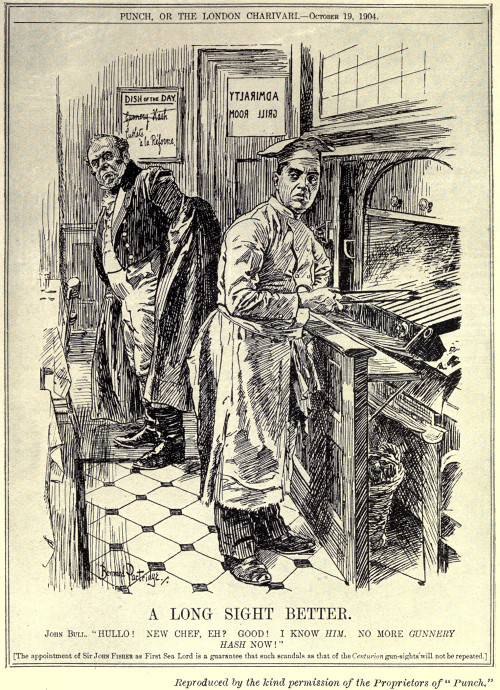

"A Long Sight Better" 196

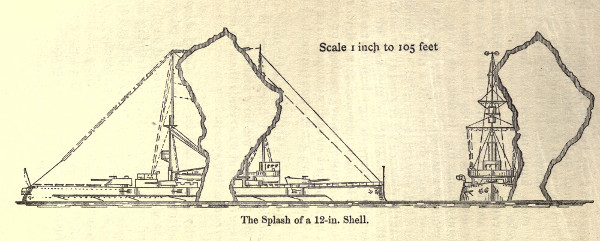

The Splash of a 12-inch Shell 245

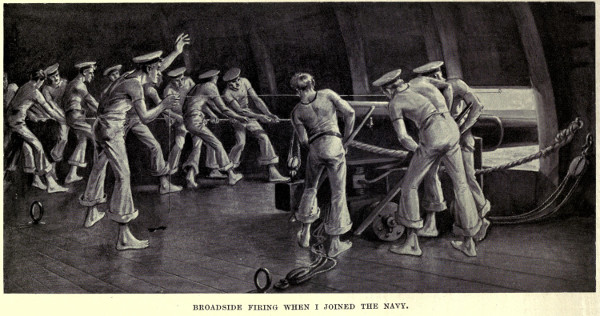

Broadside Firing when I joined the Navy 256

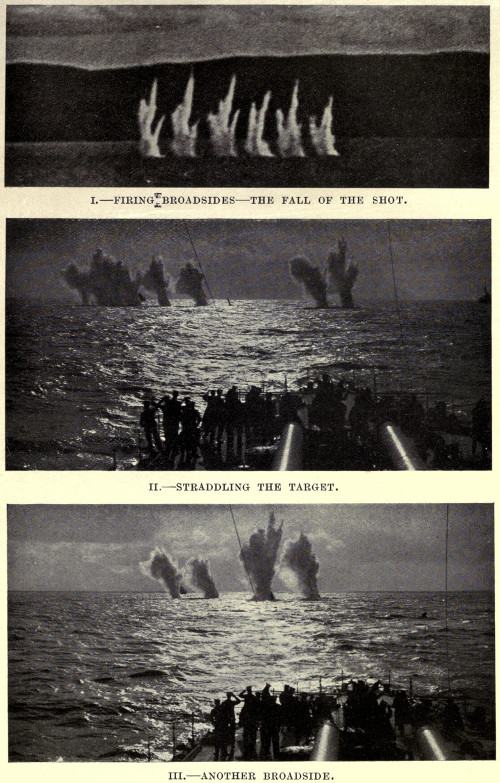

Naval Gunnery: Broadside Firing 258

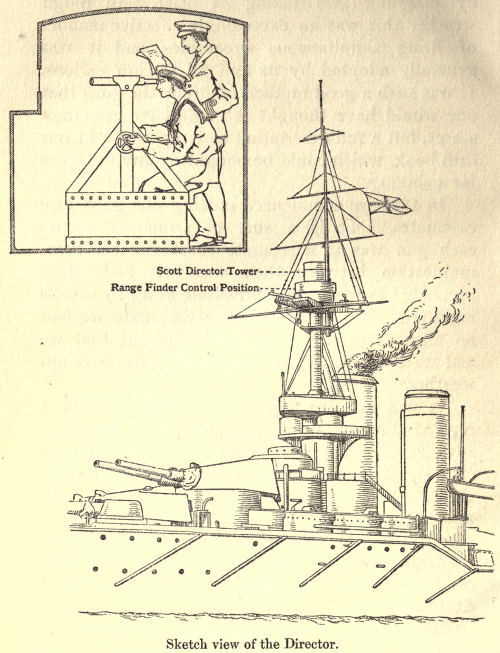

The Scott Director Tower 260

Model that I took to the Admiralty to show how the Observer would fare owing to the Funnel being in the Wrong Place 264

H.M.S. "Lion" before and after Alteration of Observation Tower 266

My Occupation when the Admiralty, had they appreciated my Director Firing, would have kept me busy 268

The Dummy Fleet 284

3-inch Anti-aircraft Gun in Action 312

3-inch Anti-aircraft Gun being Transported 312

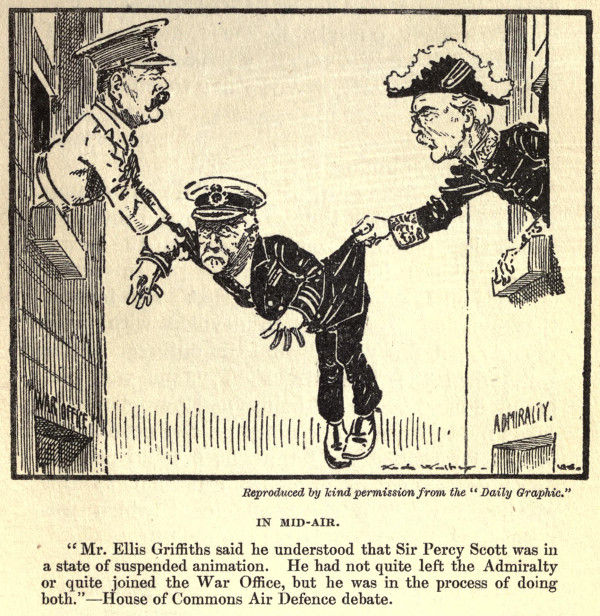

"In Mid-Air" 317

"Dual Control" 318

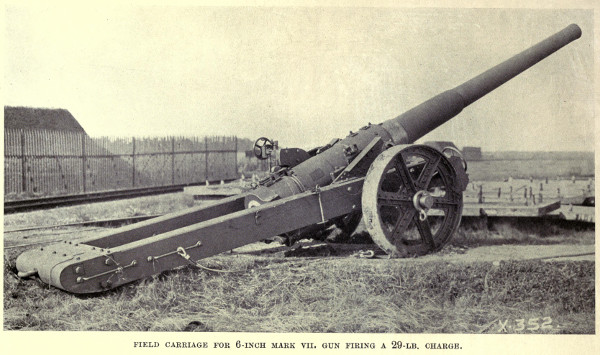

Field Carriage for 6-Inch Mark VII. Gun firing a 29-lb. charge 322

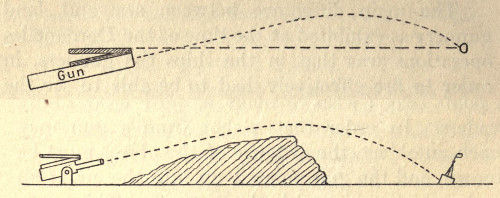

Angle Firing 330

IN this volume I have set down the recollections of a lifetime of sixty-five years. It deals with my service in the Royal Navy during a period of over half a century. I entered it when most of the ships were propelled by wind, steam being only an auxiliary; our gun carriages differed little from those of Queen Elizabeth's day; midshipmen were punished in peculiar ways, and seamen received the "cat" for comparatively minor offences. In 1913 I was retired at my own request, and I thought that my active career had ended. I was mistaken, for, as these pages record, I was drawn into the backwaters of the War and became associated again with gunnery matters, with the fight against the enemy's submarines, and with the defence of London against aircraft, rendering to the best of my ability what service I could do to the country. I should not have decided to issue these chapters, which I began writing by way of recreation and amusement after I had gone on the retired list, if I did not hope that they might serve a useful purpose in future years.

From the time when I was a junior lieutenant I was interested in gunnery, realising its importance, and this book is devoted mainly to describing my efforts, assisted by other officers in particular, Admirals of the Fleet Lord Fisher of Kilverstone and Viscount Jellicoe to improve the shooting of the British Fleet.

How far these pages may prove of general interest I cannot tell, but they will at least show how opposed the Navy can be to necessary reforms, involving radical departures from traditional routine; the extent to which national interests may be injured owing to conservative forces within, and without, the public services; and what injury the country may suffer from politicians interfering in technical matters, which they necessarily do not understand. It is my hope that ultimate benefit may result from an honest attempt to shed light upon matters of vital concern to the nation by means of my personal record. In that belief, these reminiscences have been published, and I would only wish to add that nothing has been set down in malice. My intention has been not to attack persons, but to expose rather the weaknesses and defects of our administrative machinery, in so far as I had experience of it.

Obstinate opposition to change and reform is, in my opinion, a crime. In these days of rapid advance of science and swift development of mechanics, unless we move ahead we are bound to become retrograde. In order to hold our place in the world, in naval as well as in other affairs, we must encourage initiative, and, above all, so far as the Sea Service is concerned, inculcate in our officers ideas consistent with a modern steam Navy, instead of clinging to traditions and routines which were good in their day, but are now obsolete. And I may add that I have not much belief in the

influence of an elaborately organised Naval Staff at the Admiralty, for the best creation of that character, possessed by Germany, failed under the test of war, as Lord Jellicoe's book on the record of the Grand Fleet has revealed. The Navy does not require a greatly expanded Naval Staff sitting in offices at the Admiralty performing routine work, most of which is unnecessary and seems to be done mainly in order to swell the number of officials employed. The Service requires open-eyed, well-educated, progressive, practical seamen, spending most of their time afloat, and when employed at the Admiralty not immersed in day-to-day routine, but with time to think of the needs of the future and how they should be met.

But the root of bad naval administration lies, in my opinion, in the system by which business at the Admiralty is conducted. The civilian element, being permanent, obtains too much influence, and the naval element, which is always changing, has too little influence. The spirit in which work is done is wrong. There is insufficient incentive to encourage the best men. If a man does nothing, or next to nothing, he may be sure that he will do no wrong and his career will not be endangered; hence there arises a general desire to shirk responsibility and to evade making a decision until as many sub-departments as possible are drawn into the discussion. By that widely recognised means the individual who should act evades his personal responsibility and business is delayed, sometimes with serious results to the country.

As an illustration I will take the case of a proposal which is put forward for introducing a new way of firing the guns in His Majesty's ships, involving alterations of fittings, additional electricity, structural changes, and also affecting the engineering department. When the suggestion reaches the Admiralty the original paper will be marked to be sent for consideration to the Gunnery Department, the Electrical Department, the Dockyard Department, the Chief Constructor's Department, the Engineering Department, the Third Sea Lord, and the First Sea Lord. No limit of time is fixed; each department can keep the paper as long as it likes; it is passed from one official to another, the speed with which it moves depending upon the pleasure of each official concerned and frequently it gets lost. I know of one case in which a letter took upwards of a year to circulate through the various departments of the Admiralty.

I suggest that this routine is radically wrong and would not be tolerated by any man accustomed to run a commercial firm. He would determine to obtain the opinions of all concerned in any suggestion in the quickest possible time. First of all some one would decide if there was anything in a proposal which merited its being examined. If the decision was in the affirmative, several copies would be typed and one copy sent to each person whose opinion it was desired to obtain, bearing the date and time when it was sent out and the date for its return. In due course, the various replies would reach the heads of the firm and the matter would be dealt with. Under some such system business men conduct their affairs, and they are amazed when they are brought in contact with the Admiralty and other public departments.

War suspended to some extent this slow and cumbersome method of conducting affairs at the Admiralty, but my impression is that it was not until Lord Jellicoe, on becoming First Sea Lord and realising the trouble, put his foot down, that the task of completing the reorganisation of the Fleet for war made considerable headway. Lord Fisher, it is true, speeded matters up, but he was at the Admiralty only for a short period; when he left the routine was re-established and the administration lumbered along slowly, to the despair of many officers who realised what was needed.

Lord Jellicoe returned to the Admiralty as First Sea Lord to find that the administration had been slowed down at a period when the enemy submarine campaign threatened every British interest. With a strong hand he wrenched the Admiralty from its conservative ways and, as Admiral Sims has told us, the orders which he gave for auxiliary craft and tens of thousands of mines, and the encouragement which he lent to scientists enabled us to master the greatest menace which had ever threatened not merely the British Fleet, but the British Empire.

War is the supreme test of a naval administration, and under that test the routine system of the Admiralty, which is slow, was found wanting. Napoleon once declared: "Strategy is the art of making use of time and space. I am less chary," he added, "of the latter than the former. Space we can recover but time never". Because Admiralty administration is deplorably slow, it proved unsuited to war, and the nation owes much to Lord Fisher and Lord Jellicoe for their efforts to speed matters up,

for in war the enemy does not wait on the convenience of a Government department in which almost every one, civil and naval, is nervous of taking responsibility and acting swiftly and decisively. Successful war-making depends in a large degree on time-saving rapid, decisive action. The country suffered unnecessarily, and the war was unduly prolonged because that principle was so often ignored.

It is for the country to decide whether the Admiralty shall fall back into its old ways. The policy of circumlocution and delay lies at the base of our bad administration, and not, I am afraid, by any means at the Admiralty only or at the Admiralty conspicuously. At any rate, writing of things I know at first hand, I am convinced we can never hope to obtain a Fleet well equipped, well organised, and well trained, until this system of evading responsibility at the Admiralty is broken, the circulation of papers is speeded up, and the official who shirks responsibility is made to suffer, instead of being promoted as "a safe man." Individually Civil Servants are men of wide interests whom it is a pleasure to meet, but the system of the Civil Service is, in my opinion, a public danger. This book has been written in vain if it does not carry conviction that our naval administration is based on wrong principles.

ENTRY INTO THE NAVY

THE association of my family with the Royal Navy goes back for four generations; my great-grandfather was a captain in the Service. My grandfather was a doctor and a man, I believe, of considerable talent. He attempted some innovations in surgery an art which has, of course, been revolutionised since his time; but the medical profession in those days did not welcome any departure from their recognised and often primitive methods. His inventions included some instruments for assisting the deaf, which I understand came into general use after his death. In the course of my career I was to experience the same sort of attitude on the part of those in authority, and I have sometimes reflected with a passing bitterness how little the obstructive attitude of one generation in such matters differs from that of another.

My father was a solicitor, a good linguist and an excellent public speaker. Foreign business or the gaming-tables took him to Baden Baden once a year, and I am told that he was a perfect loser. He was always very good to me and gave me advice that has been invaluable. It was a principle with him never to make a fuss about anything, and he impressed upon me that every occurrence, whatever it might be, should be taken with imperturbable quiet. He would quote that passage from "Pelham" who declares that among the properly educated a calm pervaded all their habits and actions, whereas the vulgar could take neither a spoon nor an affront without making an amazing noise about it.

In discussing my future career, he would point out to me that in a household a fussy person could only disturb the few inmates, but in a ship one fussy person might disturb what was equivalent to a whole village. How true I have found that statement in H.M. Navy! His ideas on education were as quaint as those which exist at some of our large English schools and colleges. He wanted me to be taught only Latin and Greek, as he declared that those languages were the foundation of everything. I read Cassar with him, and having won the first prize at my dame's school, thought I knew something. Then I went on to the University College School and continued to thrive on Latin and Greek.

At 11 1/2 years of age I got a nomination for the Navy and was sent to Eastman's Naval Academy at Portsmouth. I shall never forget my first interview with the Headmaster. He asked me what I knew. I rather proudly replied that I had done "As in Presenti, Propria qui maribus, Caesar, and had started Ovid." He told me that they required living languages in the Navy, and that I was dreadfully backward in all useful subjects. He added that I should have to work half my playtime, and even then he doubted if I should be able to pass the qualifying naval examination. Subsequently he took a great interest in me, was most kind in helping me with my extra lessons, and a month before the examination prophesied that I was sure to pass.

The exciting day for us all at length arrived, and about a hundred little boys presented themselves at the Royal Naval College, Portsmouth, for examination. A week afterwards I was gazetted a naval cadet in H.M. Navy. Sixty-four had passed in. I was forty-sixth on the list and one place above me was a candidate who was destined to become Field-Marshal Viscount French. Forty years later we, side by side, marched past H.M. King Edward VII at Aldershot. Sir John French (as he then was) commanded the Army and I the Naval Brigade.

Before joining the Britannia we naval cadets were given a month's leave. My father thought it would be a good thing for me to see something of the war then in progress between Prussia and Austria, so he took me to Germany. The Prussians entered Wiesbaden the day we arrived.

On the 26th August, 1866, 1 went to Dartmouth and joined H.M.S. Britannia. She was an old three-decker, fitted with a large mess-room for the cadets. We each had a sea chest and we slept in hammocks. The decks were well saturated with salt water every morning, summer and winter, and the authorities considered that this hardened the cadets. Possibly it did; at any rate it weeded out those who were not strong.

We were kept in very good discipline. The birch was used freely. It was administered publicly with great ceremony, and was the only punishment that incorrigible boys did not like. No idea of disgrace was attached to it, but it hurt. How stupid it is to talk of doing away with the birch at our public schools! In a large community of boys there will always be a small percentage of very black sheep who have no good side to their nature to appeal to, and who, unless well birched, will encourage other boys to follow their bad example.

Shortly after I joined it was rumoured that the damp and evil-smelling old ship was not a suitable home for boys of between thirteen and fourteen years of age, and that she was to be done away with. The Commissioners of the Admiralty considered the question, and successive Boards discussed it, but as the matter was important they did not act hastily their deliberations, in fact, extended over about thirty years. Finally, in 1898, work was begun on a college on shore in place of the Britannia, and the old ship of many memories was doomed.

We started from Sheerness, and en route to Portsmouth we youngsters were fortunately introduced under sail to a gale of wind. Four hours on deck, close-reefing the topsails and clearing away broken spars, probably cured every one of sea-sickness for the remainder of their lives at any rate, it cured me. An excitement of this sort is, I believe, the only cure for sea-sickness. We got to Spithead, and we midshipmen were delighted at being turned out in the middle of the night for a collision. Colliding with or being rammed by another ship, or ramming another ship, is a necessary part of an officer's education. In this case the barque Blanche Maria had got across our bows, at the change of the tide. There was a lot of crunching, but eventually we got clear without much damage. The Blanche Maria said that we had given her a foul berth; we declared she had dragged her anchor. However that may be, we midshipmen were all delighted at having seen a collision.

We left Portsmouth on the 2nd October, 1868, practically to make a sailing passage to Bombay, via the Cape of Good Hope. This we accomplished in a little over three months.

In those old sailing days in fine weather it was very delightful; a man-of-war was a gigantic yacht, scrupulously clean, for we were seldom under steam and as a consequence did not often coal. Shortage of water for the purpose of washing was our great inconvenience; our Commander, either for economy or to save the dirt of coaling, made a great fuss about the coal used for condensing. Consequently we were very often short of water for washing; water for drinking was not limited. On the main deck there was a tank with a tin cup chained to it, so that any one could get a drink. But there was a little waste, as the men did not always drain the cup dry. In order to check this, the Commander introduced what was called a " suck-tap"; the tap and the cup were done away with and a pipe placed in lieu of these, and any one wanting a drink had to take the nasty lead pipe into his mouth and suck the water up; it was a beastly idea, which our new Commander immediately did away with.

In the evening the men always sang, and it was very fine to hear a chorus of about 800 men and boys, many of the latter with unbroken voices. We had one young man who used to sing "A che' la morte" and other tenor songs from Verdi's operas, as well as many singers that I have heard on the stage. The songs, however, were not always of this high class.

'Cause 'is wife was dead, poor soul;

Round 'is waist 'e 'ad an apron,

Because 'is breeches 'ad a 'ole."

We midshipmen knew all the men's songs, and their parlance, which was sometimes strong; many of their comparisons and similes were often witty and quite original.

During the Great War some people seemed to think that milk, butter, cheese and vegetables were necessities of life. In my first ship there were about 750 men and boys in the perfection of health and strength. Their rations at sea consisted of salt beef, salt pork, pea soup, tea, cocoa and biscuit, the last named generally full of insects called weevils. Later on, preserved beef was introduced; it was issued in tins, very convenient for making into paint pots and other recepticals. Its official name was "Soup and bouilli "; the bluejackets called it by various names "soup and bullion," "two buckets of water and one onion," or it was called " bully beef," but the most common name was "Fanny Adams." At the time of the introduction of this preserved meat into the Navy, a girl called Fanny Adams disappeared, and a story got afloat that she had been tinned, or as the Americans would say canned. To this day the tins which contain preserved meat, and which are utilised for all sorts of purposes, are called "Fanny's."

En route we found out what a magnificent seaman our Captain, John Hobhouse Alexander, was, and what a bully we had in our Commander. We midshipmen had a terrible time with the latter. I contradicted him once, and as I happened to be right, he never forgave me. I saw more of the masthead than I did of the gun-room mess. Sending a boy to sit up at the masthead on the cross-trees was a funny kind of punishment. In fine weather with a book it was rather pleasant; in bad weather you took up a waterproof. Masthead for the midshipmen, and the cat for the men, was the Commander's motto. I saw one man receive four dozen strokes of the cat on Monday and three dozen on Saturday, and he took them without a murmur. That is the spirit which made this a great country; we love men who take punishment without flinching. This particular Commander revelled in flogging, and the sight of it seemed to be the only thing that gave him any pleasure. It was a form of self-indulgence which finally led to his ruin.

On arrival at Bombay, Captain Alexander went home. We became the Senior Officer's ship on the East Indies Station, and flew the broad pennant of Commodore Sir Leopold Heath, K.C.B. He was a clever, kind and able seaman. He made me his A.D.C., an honour which I appreciated, but which got me into further trouble with the Commander, as he did not approve of it. I had more leave stopped than ever and was continually under punishment. However, an end came to it all under the following circumstances. While the Commodore was up country in Ceylon, an able seaman refused one morning to obey an order. The case was investigated by the Commander, and at one o'clock two hours later the offender received

We spent a good deal of time on the East Coast of Arabia, looking for slave dhows, but only caught one. She was a small craft about 40 feet long, but had on board a crew of five Arabs and eighty slaves, consisting of ten youths, twelve women, thirty-seven girls, twenty boys and one baby. Those wretched beings were naked and horribly emaciated, and had been so crowded that most of them during their eighteen days' voyage had not moved from the position they were packed into. We took the slaves on board, washed and fed them and dressed them in some sort of clothes and then, having landed the Arabs, used the dhow as a target. We opened fire on her with all our guns, but expended a quarter's allowance of ammunition without result and finally sank her by ramming. This was my first lesson in gunnery.

The eighty slaves had come from a village a few miles north of Zanzibar. While the men were away fighting another tribe, the Arabs had swept down and marched off all their women and children, embarking them for the Persian Gulf, where they would have got, on an average, about £20 a head for them. The baby slave was rather a difficulty, as none of the women would look after it, but the boatswain made a sort of cradle for it, a feeding arrangement was extemporised, and the child did very well. We eventually landed the whole eighty at Aden, and got prize bounty at the rate of £5 apiece for them. A midshipman's share of the prize was £l 4s. 6d.

At Zanzibar the slave market was in full swing. It was quite a large place in which all the slaves sat round in concentric circles, with spaces in between so that the buyer could pass through and inspect them. They were arranged according to their "chop," or quality. A first "chop" man meant extremely good physique and youth. The women were divided into two classes, those destined for work and those suitable for adorning an Arab's harem; a nicely rounded-off maiden of eighteen or twenty years could not be bought under about £40.

It was a loathsome sight to see the rich old Arabs inspecting these girls as though they were so much merchandise. The Arabs looked dirty and generally had horribly diseased eyes, upon which the flies settled; they were too lazy to brush them off. When I visited Zanzibar thirty years afterwards I found that an English cathedral had been erected on the site of the slave market.

In chasing one dhow we went too near the shore and bumped on a coral reef, whereby all our false keel was knocked off and we leaked badly for the remainder of the commission.

Our new Commander was a great success. He gave us midshipmen plenty of boat-sailing, took us on shore to play cricket, and encouraged sport of every kind. He made us dress properly, and in appearance set us a fine example. He took a long time over his toilet, but when he did emerge from his cabin it was a beautiful sight, though he might have worn a few less rings on his fingers.

The ship he absolutely transformed. All the blacking was scraped off the masts and spars, and canary-yellow substituted. The quarter-deck was adorned with carving and gilt, the coamings of the hatchways were all faced with satin-wood, the gun-carriages were French-polished, and the shot were painted blue with a gold band round them and white top. Of course we could not have got these shot into the guns had we wanted to fight, but that was nothing. Some years afterwards the Admiralty issued an order forbidding the painting of shot and shell.

In a sailing ship the midshipmen were brought into very close contact with the seamen, always working with them aloft, on deck, and in boats. This I think was a most desirable practice, as the officers acquired at an early age that knowledge of the men's customs and ideas which is really the key to managing them. If officers nowadays knew more about their men there would be fewer defaulters.

One thing I learnt was how the sailor hated Sunday. When he was turned out in the morning it was hurry out, it is Sunday; hurry over dressing, it is Sunday; hurry over breakfast, it is Sunday; get out of this, it is Sunday. At 9 A.M. he was fallen-in on deck and his clothes were inspected by his Lieutenant, whereby he might get into trouble. Then the Captain walked round and inspected clothes, and he again ran the risk of something being wrong with his uniform. Then the Captain went below and inspected every hole and corner of the ship. This occupied about two hours, during which the men were left standing on deck. At 11 o'clock there was church, which generally was not over until after 12, so the men got a cold dinner.

12 ENTRY INTO THE NAVY

In those days there were widely different opinions about uniform, and great trouble was caused. Some Captains encouraged men to ornament their clothes with embroidery; others did not like it, so men had to cut it out again if they went from one ship to another. Some Captains allowed their officers to wear any fancy uniform they liked; others insisted on their wearing a blue frock-coat, even on the West Coast of Africa. One Admiral always wore a white billycock hat instead of a uniform cap; another wore a tall white Ascot hat.

There was no promotion by merit, all went by patronage. Every Admiral on hauling down his flag was allowed to make his Flag Lieutenant into a Commander, and if a death vacancy occurred on his station he could promote whom he liked, generally a relative. Admiral Fremantle, in his memoirs, says: "The young officer so promoted often had no merit, and his promotion was a gross injustice to those senior to him." ("The Navy as I have known it" (Cassell & Co.)) This was the general opinion in the Navy, but the abuse continued until about 1880.

GUNROOM PUNISHMENTS 13

Our gunroom was sometimes conducted very well. The youngsters who misbehaved themselves were tried by the seniors, and if found guilty "cobbed," that is, got two dozen smacks with a dirk scabbard. If they had been reported to the Captain they would have lost time, and their careers in the Navy would, perhaps, have been spoiled. The gun-room corrective while in operation hurt the boy; the service punishment hurt his career and brought grief to his parents.

At Trincomalee we transferred the flag to another frigate of 51 guns, the Glasgow, and started under sail on our homeward voyage of about 12,999 miles.

The night before reaching Sheerness, off Dungeness, we had our second collision; a steamer ran into us and did a good deal of damage. Had we been a merchant ship instead of a strongly built frigate, we should have been sunk. The steamer did not stop to ask how we were, but made off as fast as she could. The Admiralty had great difficulty in tracing her, but they eventually got her.

On the 17th February, 1872, we paid off, having been in commission for three and a half years. To the midshipmen it was a sound three and a half year's education in seamanship and in travel. We had seen the ship twice go on shore, and twice in a collision. This constituted my introduction to the old Navy of the sailing-ship days. Little did I think that I was to live to see every familiar thing disappear, and to watch the growth of a new Navy, with marine turbines, high-powered guns, automobile torpedoes, and to discuss the relative value of the Dreadnought and the submarine.

I was gazetted a Sub-Lieutenant on the 17th December, 1872, and went to the Excellent and the Naval College at Portsmouth to complete my examinations. By July, 1873, these were finished, and as the Ashantee War had broken out, I volunteered for service on the West Coast of Africa. Commodore William Nathan Wrighte Hewett, V.C., was going out in the 10-gun screw frigate Active, and he applied for me. There was, however, no room for me in the ship, as she had already twelve sub-lieutenants on board, so I took passage out in a hospital ship and joined the Active at Cape Coast Castle. I was distressed that I could not land with the Naval Brigade; however, we people who were left at the base had a busy time of it.

In December plenty of troops had arrived, but the advance was delayed by the difficulty of getting carriers, for the roads were impassable for vehicles or mules. Each man carried 70 lbs., a woman 40 lbs., and a child 15 to 20 lbs. for a distance of seven miles. One woman gave birth to a baby en route; she put it in the bush. On her return she picked it up, placed it in her empty packing case with a bunch of bananas, and arrived at Cape Coast Castle, smoking and smiling, with the packing case, bananas, and baby on her head.

The Naval Brigade, under Commodore Hewett, V.C., landed at the end of December, and on the 6th February, Coomassie was entered and burned, and peace followed on the 13th.

In the engagements, Lieutenant A. B. Crosbie, R.M.L.I., Sub-Lieutenants Gerald Maltby and Wyatt Rawson were wounded, and Sub-Lieutenant Robert Munday was killed. Sub-Lieutenants Ficklin and Bradshaw died of fever. Each of these three young officers was an only son.

In this campaign the Active received the following promotions and honours: Commodore W. N. W. Hewett, V.C., to be K.C.B., Staff-Surgeon Henry Fegan to be C.B., and Lieutenant Adolphus Brett Crosbie was "mentioned."

At the conclusion of the campaign I broke my leg, and was sent to hospital at the island of Ascension. I soon got well, but could not go back to my ship, so I had an opportunity of studying this unique island. It is treated like a man-of-war; it has a captain, officers and crew, with a few of their wives, but no other inhabitants. If a baby is born on the island, its name is put on the books and provisions allowed for it by the Admiralty. There are no shops, but certain things can be purchased at a canteen, and you buy your clothes from the Cape of Good Hope, 1600 miles distant. All the lower part of the island are lava and clinker. In the centre stands Green Mountain, a peak of cinder, from whose summit you look down on the craters of about a dozen extinct volcanoes. On the mountain the cinders, decomposing under the tropical sun's rays, have produced a rich soil in which everything will flourish. I was told that if you put your umbrella in the ground it would grow.

The energetic naval inhabitants had put down pheasants, partridges, and rabbits, and there were about six hundred wild goats. I should think they are there now, as they are very difficult to shoot. I spent all day and every day stalking them, but got very few.

The remaining part of 1874 brought the Active some lively work. We got information that a trading schooner, the Geraldine, while beating up the Congo River, had got on shore, and had fallen a victim to the pirates who infested the river. The bandits had boarded the vessel, killed the crew, and looted her. We went off at once at full speed and anchored in the delta of the Congo.

On the following day, the Commodore, with a small party of officers, proceeded up the river in a gunboat. We inspected the Geraldine, and found she had been gutted; the pirates had even commenced stripping the copper off her bottom. We then went on to a trading station about forty miles up, and all the native chiefs were summoned to a palaver.

They arrived, armed, in war canoes; we had journeyed up without arms, notwithstanding the apprehensions of the traders. Sir William Hewett, however, did not know the meaning of fear. Through our interpreter, he told them that unless they produced at once the murderers, he would later on, in the dry season, return and burn every village from the mouth of the Congo to where we were then. The chiefs refused to give up the murderers (a decision which pleased us young officers), so we returned to the Active, and for the next few months were busy with preparations. All boats were plated with one-eighth inch steel plate from the gunwale two feet up; guns, rockets, provisions, and transport were provided.

On nearing a village the boats carrying the guns shelled the place all round as a preliminary to the landing of the marines (this was practically an artillery barrage, which, thought to be new in 1917, was used in 1874), who formed a cordon and fired into the bush, while the remainder of the brigade disembarked. An advance was then made, firing the whole time. The villages were generally found deserted and a search usually revealed some relic of the Geraldine. Such operations ended with the destruction of the village and canoes by fire. Thus Sir William Hewett kept his promise of burning everything from the entrance of the river to Punta-da-Lenha. The lesson effectually stopped piracy, and increased trade in the river.

At some of the villages the natives fired a great deal, but our entire loss was only one killed and six wounded. The forethought of the Commodore in armouring our boats saved a great many casualties, as slugs discharged by the natives were harmless against the steel plating.

STEAMBOAT SERVICE 19

At night the boat was sometimes a very trying place to live in. Anchored up a creek, with a rain awning over the top of the armour plating, no fresh air could get in or foul air out, and the total of seventy occupants inside, including thirty black men, worked out at about ten cubic feet per man a condition which is, I understand, according to the laws of hygiene, impossible for a human being to live in. We managed to live, but it was not pleasant, and I was always glad when the morning came. We should have liked to bathe, but as a crocodile rose to everything that was thrown overboard bathing was not permissible. The hippopotami during the night were a source of annoyance; they breathe so noisily through their wide-opened mouths. But though they came very near the boats they did no harm.

20 ENTRY INTO THE NAVY

Their Lordships the Commissioners of the Admiralty signified their appreciation of the expedition by making the following promotions: Sub-Lieutenant Percy Scott to be Lieutenant, and Sub-Lieutenant A. C. Middlemas to be Lieutenant.

In November, 1875, at Lagos, Commander Verney Lovett Cameron came on board the ship, having just completed a walk across Africa from sea to sea. He started from Zanzibar in 1873 with two companions, to visit Dr. Livingstone. It was their ill fate to find the famous explorer dead. Captain Cameron completed his long walk alone, his companion turning back. His walk as the crow flies was 2000 miles; by the route he took it was 3000 miles. As the Americans say, it was some walk!

Whereas 1874 and 1875 had produced plenty of expeditions and promotions for the Active, 1876 opened peacefully, and the sub-lieutenants who had recently joined complained of the humdrum state of affairs. They had not long to wait for a change. Before the end of January a letter arrived from the Governor of Lagos, stating that the King of Dahomey had been maltreating British subjects, and asking for Naval assistance. The Commodore a man of action, if ever there was one gave us twenty-four hours to coal, provision, and fill up with ammunition, and we were off at full speed for Whydah, the port of Dahomey. We arrived there in February, inquired into the case, and the

The Commodore was full of fight, and "taking Dahomey" was the only topic of conversation. But we hung about Whydah for some time waiting in vain for the authorities at home to make up their minds as to what was to be done. The golden opportunity of seizing Dahomey was lost, and as subsequent events proved the task fell to the lot of the French.

Whydah was not a very nice place to blockade, as it is situated in about the hottest part of the coast of Africa, and we were overjoyed when one day a steamer came along with a signal flying "Important dispatch for you." The dispatch was sent for, and in ten minutes steam was ordered for full speed and preparations were at once commenced for a landing party on a large scale.

What the official instructions disclosed was that an English steamer had been attacked by natives in the River Niger. The steamer had engaged in regular trade up the river to the resentment of the natives, who were determined to capture her. Their method of attack was ingenious. As soon as the vessel had passed the village of Akado, they prepared for her return by stretching a rope across the river 150 yards at this spot well securing the ends of it round trees on the bank. I saw a piece of this rope later and found it to have been made of strong fibre plaited together so as to form a cable about eight inches in diameter. It was kept on the surface by large cottonwood floats.

We arrived off the mouth of the Niger on the 27th July, 1876, and our landing party, with guns and rockets, were transferred to the gunboats Cygnet and Ariel. The guns and their crews were put on board the local steamer Sultan of Sokato. On the following day the three ships proceeded up the river to Akado, and found the ends of the hawser, some well-dug rifle-pits, and three small cannon. There being no sign of life, however, the little squadron moved on to the town of Sabogrega. Here, on attempting to land, the men were met by fire from rifle-pits behind strong stockades. A bombardment of the stockades was maintained throughout the night and in the morning the whole brigade were embarked in boats and at a given signal dashed in under a heavy fire. The stockade was carried, the native force driven back, and the town burned.

Our losses were five officers wounded, one man killed and nine wounded. Among the wounded were the Commodore's secretary, Cecil Gibson, and our chaplain, the Reverend Francis Lang. They were not in the landing party, but seeing a wounded seaman on the beach they pulled ashore from the gunboat in a dinghy to bring him off. A native in hiding fired at them while they were lifting the man up and wounded them both very severely.

We then returned to Whydah to assist in the blockade, but the Commodore, as I have said, could get no definite decision from the Government and we left for the Cape of Good Hope.

In April, 1877, our eventful commission terminated, and at Portsmouth Sir William Hewett received a great ovation. He was certainly a wonderful man. In handling a ship under sail he was a master sailor; under fire he was absolutely fearless; and his boldness and swiftness in decision were equalled by his readiness to take any and every responsibility. He had won his Victoria Cross in the Crimea, and had seen more war service than any officer in the Navy. He was too go-ahead for the Admiralty, but still, if we had gone to war, I am sure he would have been put in command of the Fleet.

At the expiration of my leave, I went for a short time to H.M.S. Warrior. We were guardship at Cowes, as Queen Victoria was staying at Osborne. One Sunday I had to take a dispatch to her Majesty. 1 had delivered it, and was feeling very proud of entering the portals of Osborne House, when to my surprise the officer-in-waiting told me not to go, as her Majesty might wish to see me. A minute or two later he was conducting

During the Crimean War the Naval Brigade in returning to the coast passed the scene of a massacre of some men, women, and children. All were dead except two very young boys, who were dreadfully wounded. The sailors picked them up, took them to their ship, and they gradually recovered. The question then arose what was to be done with them, and her Majesty solved the case by ordering them to be sent to England and housing them at Osborne. They were called Hyde after the captain of the ship which brought them here. Her Majesty had them educated at the Royal Naval School, New Cross, and they eventually joined the Navy as clerks, and both became assistant paymasters.

THE gunnery of these days was deplorable, and had been so for half a century. In the American War of 1812-14, as a humiliating chapter in our naval history records, we lost ship after ship owing to the failure to practise our officers and men in the use of their guns. One fine sailor, Captain Broke, of the Shannon, taught his men to shoot by putting over targets two or three times a week and practising firing at them both with cannon and small arms. He subsequently inflicted on the Americans their first defeat; it was by sheer good shooting that the Shannon beat the Chesapeake.

This demonstration of what good gunnery could achieve ought to have brought about an immediate reform, but it was not until fifteen years after the end of the war that the first real step was taken to educate the officers and men in using their guns.

In 1830, the Commissioners of the Admiralty decided tentatively to allow H.M.S. Excellent, an old 74-gun line of battleship at Portsmouth, to be used as a school for instruction in artillery. From 1830 to this date the Gunnery School at Portsmouth has rendered yeoman service to the country by endeavouring, against great opposition, to improve the shooting of H.M. ships of war. In the Navy, at the time I am speaking of, a knowledge of gunnery was looked upon merely as an adjunct to, and not as a necessary part of, an officer's education. Those who knew nothing of gunnery, and even boasted of the fact, laid the flattering unction to their souls that they were practical seamen. Gunnery officers were laughed at as mere pedants and coiners of long words. Admiral of the Fleet Sir Edward Seymour, in talking of the Navy in 1852, says, "In those days the chief things required in a man-of-war were smart men aloft, cleanliness of the ship, the men's bedding and her boats. Her gunnery was quite a secondary thing." ("My Naval Career and Travels,"Sir E. H. Seymour, Admiral of the Fleet: "The State of Gunnery.")

This view of what was needed in a man-of-war survived in the Navy for half a century after the date referred to by Sir Edward Seymour. For many years the all-important event in each year of a ship's commission was her inspection by the Admiral, for if the ship was not clean, the Captain would be superseded and the Executive Officer would not be promoted. Gunnery did not matter. The inspection report that went to the Admiralty

was in the form of a printed set of questions which the Admiral had to answer, but it abstained from all allusion to the state of efficiency or otherwise of the ship in target practice with her guns. Questions on this subject were not added to the report until the year 1903.

Admiral Sir Cyprian Bridge, in his book "Some Recollections" (published in 1918), describes his ship, the Pelorus, in 1857, as one of the first vessels of the Navy to possess a gun-sight, and added that it was then considered an epoch-making improvement in naval gunnery. He tells us, further, that the gun-mountings in H.M.S. Pelorus were of a pattern practically identical with those used in Queen Elizabeth's ships, and that the type survived in the Navy for twenty years afterwards. This pattern of mounting was in use when I joined the Navy. It had a life of about four centuries, but Sir Cyprian warns us that we must not infer from this that the Admiralty were backward in introducing improvements in ships' armaments although I point out in this volume that the Admiralty in my time have been, and still are, very backward in this respect. I cannot contradict Sir Cyprian Bridge as to the attitude of the Admiralty in 1857, but four hundred years for one pattern of gun-mounting appears a long time! It looks rather like our clinging to masts and yards forty years after they ought to have been abolished!

Sir Cyprian suggests that the stories which have been current of late years as to the want of attention to gunnery in the older Navy were unworthy fabrications. That statement hits me rather hard, because I have so frequently asserted the contrary,

but in doing so I only took into consideration my own fifty years' experience in the Navy. This is the only mention that Sir Cyprian makes of gunnery. His "Recollections," like those of most of his contemporaries, consist largely of descriptions, interesting descriptions, of the places visited.

After an inspection in my early years it was customary with many Admirals to send the Captain of the ship a memorandum containing the gist of the report dispatched to the Admiralty . If the Admiral's memo, was unfavourable, it went into the waste-paper basket; if favourable, copies of it were made and circulated in the ship, and sometimes they got into the Press. Here is one copied from the Naval and Military Record of September, 1902.

3rd of September, 1901.

"I have made the following remarks in the report of the inspection of H.M.S. Astraea under your command:

"' Ship's company of good physique, remarkably clean and well dressed; state of bedding, specially satisfactory.

"' The stoker division formed a fine body of clean and well-dressed men. "' At exercise the men moved very smartly.

"' The ship looks well inside and out, and is very clean throughout. Her state is very creditable to the Executive Officer, Sir Douglas Brownrigg.

"'The tone of the ship generally seems to me to be distinctly good.

H.M.S. EXCELLENT 29

This was a typical inspection of the period. It contained no reference to the fact that the Astraea was one of the best shooting ships in the Navy, nor did her captain and gunnery lieutenant get one word of praise for all the trouble they had taken to make the ship efficient as a fighting unit of the Fleet. It was only her success in tailoring and house-maiding and the state of the bedding that secured commendation. No wonder that the captains and gunnery officers of ships came to the conclusion that they must devote their time and attention to the appearance of ships and not to battle-worthiness.

I have referred to this inspection report to show how conservative the Navy was. Forty-nine years had not changed what Sir Edward Seymour says were the ideas in 1852; the cleanliness of the ship and the state of the men's bedding were still regarded as the most important factors of efficiency.

In 1878 I joined H.M.S. Excellent to qualify as a Gunnery Lieutenant. She was an old three-decker, very badly found as regards the necessary equipment for instruction in gunnery, so much so that a lecture there on some particular weapon generally concluded with the remark "but this is obsolete, and we have not got the new one to show you." In those days a lieutenant qualified in gunnery was an important asset in a man-of-war. He was the only officer in the ship who knew anything about gunnery, and in an action he would have had a great responsibility.

Our course of instruction was divided into two parts practical and theoretical. The former consisted of learning how to load and fire the guns and how to train the men, and was also concerned with powder and ammunition and projectiles. The theoretical part embraced differential and integral calculus, conic sections, algebra, chemistry, physics, and a few other subjects with long names. It was obvious that the practical part should have been taken first as, in the event of war breaking out, we thirty lieutenants could have been sent to sea with sufficient practical knowledge to manipulate the artillery. Our instructor, a most brilliant lieutenant named Tyne Ford Hammill, informed us that, although it was wrong, we had to do the theoretical course first. With a twinkle in his eye, he explained that the defect had been pointed out, and that it would be changed, but as the authorities did not move very quickly in gunnery matters it would take time. He was quite correct. The system was changed, but not till twenty-six years afterwards.

The officers of H.M.S. Excellent took a great interest in target practice; it was carried out from old gunboats, which were light and consequently rolled a great deal. This made the practice very difficult, and I think I can show that in those days a good shot had to be born, he could not be made.

The man who pointed the gun and fired it stood about six feet in rear with a string in his hand which, when pulled, fired the gun. On the gun were two pieces of metal about four feet apart, one was shaped like a V, the other like a V upside down. To hit the mark the gun-layer had to pull the string when the V, the inverted V, and the target were all seen in one line from his eye. In order to arrive at this all three must be seen very distinctly.

In other words, the eye had to see three objects; one at six feet, one at ten feet, and the other at 3000 feet, all sharply defined. This called upon the eye to do more than any camera will do unless it is very much stopped down. The eye is a very fine optical instrument and has in certain circumstances sufficient range of focus to comply with the requirements I have mentioned; but it will only comply with these requirements under certain conditions of the stomach and general state of health. We will call this having the eye in order No. 1 necessity for hitting the mark. The firer in those days had orders always to fire as his gun was rolling upwards; as the roll would impart an upward movement to the shot, he had to pull the string a little before the two V's came in line with the target, but the roll varied, so the "little before " varied and he had to judge how much to allow. We will call this No. 2 necessity for hitting the mark.

Then came the forward motion of the ship from which the man was firing. This would cause the shot to go forward and miss the mark, so he had to have his V's a little behind the target when he pulled the string. This is No. 3 necessity for hitting the mark. To acquire and put into practice correctly these three requirements appears impossible, but I have seen men place shot after shot within a foot of a small flagstaff 1000 yards distant from them. Truly the brain and eye can work together in a wonderful manner.

Of many hundreds of seamen whom we trained in shooting, one or two per cent, could do what I have mentioned. The objective of the staff officers of H.M.S. Excellent was to find some rules or means of instruction that would increase the percentage of these men, but we landed on another difficulty which quite stumped us.

A lieutenant - I wish I could remember his name - pointed out that some men for the same amount of roll fired earlier than others, but obtained the same results; in other words, that some men when they did a thing did it quicker than others.

A very clever torpedo lieutenant of H.M.S. Vernon took the matter up and declared that a certain amount of time elapsed between the man at the end of the string wishing to pull it and his actually pulling it; he described it to me that the eye when the objects were in line telegraphed to the brain that the string was to be pulled, the brain telegraphed to the muscles of the hand to pull it, and he pointed out that these two telegraphs occupied a certain amount of time, and that this amount of time varied with different people. To prove his theory a machine was made - I think it was called the personal error machine. Captain (afterwards Lord) Fisher, in explaining it

to Queen Alexandra, called it the Foolometer, as he said it measured how much of a fool you were; you thought you did a thing instantaneously but you did not, and this machine registered how much time elapsed between your thinking you had done a thing and your doing it. The machine was very simple, as far as my memory serves me, and it is forty years ago. The person being tested was told to pull a string when he saw the pointer move of a galvanometer which was in front of him.

What happened was as follows: An electric current was sent through the galvanometer which caused the pointer to move; it also caused a mark to be made on a revolving cylinder. When the person being tested pulled the string, it caused a mark to be made on the cylinder. The distance between the two marks represented the time that elapsed between the eye seeing the pointer move and the hand pulling the string.

This little lecture shows that the man who pulled the string, or, as he was more commonly called, the man behind the gun, had a lot to think about.

The whole gunnery establishment consisted of two line-of-battle ships (the Excellent being connected by a bridge with the Calcutta), a very old turret ship in which we learned turret drill, some gunboats which, as I have said, took us out for target practice, and an island where we were taught infantry drill.

This island - Whale Island - which we very appropriately called "Mud Island," has had a peculiar history. In 1856 it was acquired by the Admiralty, and subsequently was used as a dumping-ground for the mud and clay which was excavated in forming the basins and docks of Portsmouth Dockyard. One party of convicts in the dockyard were employed in digging the clay and harrowing it into railway trucks, which went by a viaduct to Whale Island, where another party of convicts emptied them. The whole island, which is now of nearly 100 acres, has therefore been twice in a wheelbarrow; it seems almost too colossal to believe, but, as nearly 1000 convicts were working at it for about forty years, they would move a very large amount. In depositing the mud, no attempt was made to level it, or to allow it to drain itself; and consequently the whole place was a quagmire, only available for drill after a long spell of dry weather. One small portion which had been gravelled was capable of being used at any time.

Being in those days anxious to keep in training for running, I got the convicts to smooth down a track about four feet broad and a quarter of a mile round. They took great interest in it, filled up the hollows, made little drains, and planted on it every blade of grass they could secure. They even arranged with their fellow convicts in the dockyards to collect carefully any grass they could find and send it over. In a fortnight we had quite a decent track. We then sowed it with grass seed, and when it was sufficiently advanced, a party of about fifteen of us used to go up to the island at five in the morning to cut and roll it. It got on so well that we were able to have athletic sports. The success of the track suggested to me that the whole might be levelled and drained, the

Excellent done away with, and a Gunnery Establishment built on the island. The ship was rotten and would soon have had to be replaced by another; the expense of keeping her up was enormous, and she was unsuitable in every way as a School of Gunnery. I mentioned the idea to the authorities, and they thought I had gone mad. It was considered to be the most ridiculous idea ever put forward. "He wants us to live on Mud Island" was the common chaff, and I could only retort that some day the desire of all officers would be to live on Mud Island. Events justified my prophecy, and I was destined to return to Whale Island to superintend the work of construction which was to transform the mud flats into a great naval establishment.

As to the Excellent, the one notable feature of the School of Instruction was the diligence of the officers and their zeal in striving against a sea of opposition to improve the gunnery of H.M. Navy.

Having completed the course, I served for a year as an Instructing Lieutenant, and then went to sea as Gunnery Lieutenant of H.M.S. Inconstant, flagship of the Earl of Clanwilliam. The squadron consisted of the Inconstant, Bacchante, Diamond and Topase, all fully-rigged sailing ships. Prince Albert Victor and Prince George (now King George V.) were serving as midshipmen in the Bacchante.

The particular object of the squadron was to train officers and men in the use of masts and sails, which were very shortly to disappear and really should have disappeared ten years before, since they hampered a ship in speed, and would have been a severe encumbrance in an action. They certainly afforded a fine gymnasium both for nerve and body, and inculcated thought and resourcefulness, which were most valuable to men afterwards. The sailoring sailor was not a machine. You could teach him a certain amount, but he was always having to use his brain to meet unexpected difficulties as they presented themselves.

As a boy in the training ship he was taught how to furl a sail on a jack-yard close down to the deck. He found the yard laid pointing to the wind, clewlines close up, and the sail, from constant handling, as soft as a pocket handkerchief. How easy it all was! Then he went to sea and discovered the difference. On a dark night, with the ship rolling, he was awakened from his slumbers by a scream "Topmen of the watch in royals." In a pouring rain squall he had to feel his way aloft to a yard 130 feet above the deck. And when he and his mates got there what a contrast to the training ship jack-yard! The sail is all aback, wet and as stiff as a board, the clewlines have fouled, and perhaps one lift has carried away. But the sail has to be furled, and they think out some way of overcoming the difficulties and furled it is. Fine training for a boy, although it cost a good many lives!

The question of doing away with the masts and sails was the theme of much discussion. Those who favoured their abolition said that as we should have no sails it was no use wasting time, money and life, in training our officers and men to use them. My gallant Captain declared that if

you wanted to make a jockey like Tod Sloan you did not train him on a camel. What the arguments were of those who wished to retain masts and yards I do not exactly remember, but they got their way, and the sinking of the Captain, Eurydice and Atalanta, with a total of about 2000 officers and men in the prime of life, failed to alter their opinion. Sails were not finally discarded until after the sloop Condor went down in a gale off Cape Flattery on 3rd December, 1901.

On the 16th October, 1880, we left Portsmouth for a cruise round the world. The programme was to visit Madeira, St. Vincent, Monte Video, and the Falkland Islands, then sail round the Horn to India, and return home by the Suez Canal. The young Princes were to see the world. We arrived at Monte Video on the 21st December, and remained there until the 8th January, the time being spent in entertainments of every description. The Uruguayans are noted for their hospitality.

Four days before we left for the Falkland Islands, a telegram was sent by the Admiralty, ordering us to proceed to the Cape of Good Hope at full speed, and to prepare our brigade for landing, as we were at war with the Boers. The gentleman on shore who received this telegram put it in his pocket and forgot to open it until after we had left, so away we went 1400 miles in a southerly direction instead of going east where we were wanted.

When at length the telegram was opened at Monte Video, a gunboat, the Swallow, was dispatched with orders to try and catch us. The speed of the Swallow did not quite do justice to her name. We reached the Falkland Islands on the 25th January; the Swallow arrived the following day, and our Admiral the Earl of Clanwilliam at once made a signal "Prepare for immediately. Squadron is ordered to proceed to the Cape of Good Hope with all dispatch." During our 4000 miles voyage to the Cape of twenty-two days, all preparations for landing an expeditionary force were made. The men were drilled and exercised in firing, our field guns were got ready to land, and we could have put into the field a very respectable force of about 1600 men.

On the 16th February we arrived at the Cape of Good Hope and found that in December, when we were enjoying ourselves at Monte Video, the Boers had declared war upon us, and as we were, as usual, unprepared they had been successful in several engagements. In these circumstances we doubled our efforts to make our brigade efficient for landing, and hourly expected a telegram to proceed to Natal and co-operate with the forces there, for the military authorities were very short of men and our 1600 might have turned the scale. No more orders came, however, and we remained at Simon's Bay, enjoying dances and dinner parties while our troops suffered severe reverses at Laings Neck and Majuba.

By the middle of March Sir Evelyn Wood, who was in command, had sufficient troops to ensure the defeat of the Boers, but the British Government had meanwhile decided to make peace, and the task thus left incomplete had to be undertaken anew twenty years later.

After peace had been signed, we lingered on at the Cape until the 9th of April, when, to the delight of every one, we weighed anchor and departed on a 5000-mile voyage to Australia. On the 12th May we arrived off Cape Lewen, and during the night encountered some very heavy weather. In the morning H.M.S. Bacchante, with the two young Princes on board, was missing. We spread out to search, and had a very anxious three days, when fortunately we received a signal that the Bacchante had put into Albany, in Western Australia, her rudder having been disabled in the gale.

A most pleasant six weeks followed at Melbourne. Just before leaving their Royal Highnesses joined the Inconstant, as the Bacchante (which subsequently rejoined the squadron) was still under repair at Albany, and we resumed our cruise, visiting the Fiji Islands, Japan, China and Singapore.

At Singapore we said good-bye to the Bacchante with her royal midshipmen. She had been ordered home via the Suez Canal, while we were to return via the Cape. We had visited many interesting places and seen much of the world. It had been a sort of yachting cruise with endless entertainments. Professionally we had spent two years in learning how to manage a ship under sail,

but I doubt if any officer or man of the squadron was ever again in a ship with sails. Our Captain, C. P. Fitzgerald, was probably the most able seaman in the Navy in regard to the management of sails. He could work the Inconstant just like a yacht; but it would be no use mentioning some of the fine work I have seen him perform, because no one now would understand or appreciate it.

In gunnery we were no worse than any other ship. We fired sometimes, but the difficulty at target practice was to communicate the range to the guns. To overcome this obstacle I made an electrical range transmitter, and submitted it to the Admiralty in the following letter:

"At Sea,"

3rd May, 1881.

"Having found great difficulty on board this ship in getting the distance of the target passed correctly from the masthead to the gun deck, I have the honour to submit plans of an Electrical Indicator which has been made on board this ship, and seems to answer the purpose satisfactorily.

"It consists of two dials, their faces marked in hundreds of yards; one is placed at the masthead or wherever the officer is stationed to measure the distance, the other in the battery, the two being connected by electric wires.

"As the distance alters, the observer at the masthead moves the pointer of his dial to the new figure; the pointer of the battery dial simultaneously makes a corresponding movement, at the same time ringing a bell.

"The arrangement is exceedingly simple, and though only roughly made on board this ship by the armourer, it works well.

"I have the honour to be, sir,

" Your obedient servant,

"PERCY SCOTT,

"Lieut"

Fifteen months afterwards, on the 21st June, 1882, their Lordships wrote to the Admiral commanding the squadron: "You are to inform Lieutenant Percy Scott that my Lords highly appreciate the intelligence and zeal he has shown in the construction of the instrument devised by him." On my return to England, however, I found that my invention had been pirated and patented by some one else. Necessary as an instrument of this description was for accurate firing, the Admiralty did not supply it to the Service until twenty-five years afterwards. (This is an illustration of methods of administration in 1881; but things are not much better to-day.)

In the middle of May we arrived at the Cape of Good Hope and anchored in Simon's Bay, which was so familiar to me. Simon's Bay was just the same as I knew it ten years before. None of the recommendations suggested by Sir William Hewett for improving the dockyard had been carried out; there was not a fort of any description, nor was there a dock or a railway in the place.

During our stay I went for a few days' leave to Cape Town. On my return I found the ship was on fire. At 8 p.m., a couple of hours earlier, dense volumes of smoke arose from one of the after compartments. It was found impossible to locate the fire, and all the ship's fire appliances and fire engines were engaged in pumping into the compartment, but as some of the water-tight manhole doors were off for repair the whole of the after part of the ship was being filled with water, and at the same time no apparent effect was produced on the flames. Efforts had also been made to get to the fire by a man wearing the German smoke cap supplied by the Admiralty for that purpose, but he was nearly asphyxiated in the attempt.

Such was the situation on my return. Putting on one of the caps, I went down myself and succeeded in discovering the seat of the outbreak. But the labour of breathing in this horrible contrivance with its gag in the mouth and goggles that let the smoke through left one without strength to do any work. So I came up and got into a diving dress. The dress and helmet were of course very heavy, as they are made to withstand a great pressure of water, and the descent of so many ladders with this great weight was a difficult matter. However, I got down with a hose and very soon put the fire out. It had originated in one of the storerooms where there were large kegs of butter, lard, candles and the like. The butter was floating, alight, on the water, and it only needed a little water on the top of it to put an end to the mischief. But with the extinguishing of the flames the light went, and it was with some difficulty that I managed to retrace my way through the dense smoke by means of the air pipe.

During this ticklish operation the well-meaning people on top kept on pulling my rope, which is the ordinary signal to a diver to inquire if he is all right. These jerks sometimes pulled me off a ladder, and to be pulled over with one's head encased in a tremendously heavy helmet was almost enough to break one's back. Little wonder that I got back pretty nearly done up. They carried me clear of the smoke, unscrewed the face-plate of the helmet, and found that I had enough energy left in me to express in forcible sea terms my opinion of them for constantly jerking at my rope.

Incidents of this kind always teach a lesson of one sort or another. On this occasion I learned that the smokecap was of no use, that the only way on board a ship to get at a fire and extinguish it was to use the diver's dress, but that the diving dress was too heavy, and that what we wanted was some modification of it kept always ready in the event of fire.

To meet the case, I had a light helmet made out of a butter tin and attached to it a short coat with a belt round the waist and bands round the wrists. I tried this in smoke and it was most satisfactory; we adopted it in the Inconstant. I have used it in every ship I have commanded since that date, and have three times experienced its efficacy in saving H.M. ships from destruction. But the Admiralty did not bring it into use until thirty years afterwards, though I am sure it would frequently have proved of the greatest service in all ships of war. The Captain of the Inconstant reported on it in a letter as follows:

"Alexandria.

" 26th August, 1882.